Lizzie Lind-af-Hageby

Pioneer Campaigner for Animal Rights

“Juries are quite willing to believe that a coster can be cruel to his donkey, or a society woman to her child, but they are very slow indeed to believe that a “man of science” can be cruel to a dog.”

A Remarkable Woman

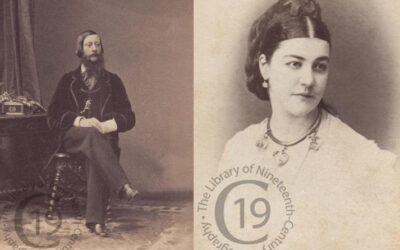

In the 1900s, a Swedish-born pacifist and women’s and animal rights campaigner, Louise Lind-af-Hageby – or Lizzie as she preferred to be called – appeared regularly in the British press for her frequent run-ins with the medical establishment. But who remembers this remarkable woman now?

I came across Lizzie’s story when researching my Encyclopedia of Women Social Reformers 20 years ago. What follows is a condensed version of a much longer, unpublished academic paper I gave at that time.

The 1900s Campaign Against Vivisection

Lizzie was born in 1878 into an eminent, upper-class family in Stockholm. Her grandfather had been Chamberlain to the King of Sweden and her father was a judge. She had taken up philanthropic work at a young age but it was her time studying at the Pasteur Institute in Paris during the Paris Exposition of 1900 that set her on the path to campaigning against vivisection. At the Pasteur, Lizzie was greatly shaken by the sight of hundreds of suffering caged animals being used in various kinds of research. With a like-minded friend, Leisa Schartau, in 1902 Lizzie came to London and enrolled at the London School of Medicine for Women to make a serious study of vivisection –which at the time was on the curriculum at the University College of London’s medical school.

At UCL the two friends attended physiology lectures involving demonstrations on animals, determined to investigate claims by medical researchers that vivisection practices had become more humane under the 1876 Cruelty to Animals Act. In February 1903 during lectures by the eminent physiologist, Professor William Bayliss, on ‘The Mechanism of the Secretory Process, a brown terrier dog was vivisected.

The detailed diaries that Hageby and Schartau kept of what they saw would form the basis of a controversial exposé by them, published as Eye-Witnesses: Extracts from the Diary of Two Students of Physiology later that year. In it, the two friends argued that the terrier dog vivisected by Bayliss had not been fully anaesthetized and had already been subjected to two previous vivisections by another professor. This was in direct contravention of the 1876 act, which ordered that an animal should be destroyed immediately the results of a single vivisection were ascertained. ‘If this is not torture,’ the two women argued ‘let Mr Bayliss and his friends … tell us in Heaven’s name what torture is.’

The Shambles of Science Trail

It was inevitable that a professional medical man of Bayliss’s standing would defend his reputation. In November 1903 he accordingly sued the publisher of Eye-Witnesses – Stephen Coleridge, general secretary of the National Anti-Vivisection Society – for libel, after Coleridge had made deliberate public accusations against him. In what would be a celebrated court case, Lizzie, on whom the prosecution focused, would spend many hours in the dock under intense and complex questioning. In the face of Bayliss’s accusations of being ‘meddlesome’ and ‘mendacious’ she answered with patience, clarity and a superb command of her facts, demonstrating an impressive and comprehensive knowledge of the practices of vivisection. She contended that many leading figures in the medical establishment, some of them nominated to monitor the enforcement of the 1876 act, were in reality, infringing the practices laid down under it.

Hageby and Schartau’s objective was uncompromising: in the introduction to their book they stated that they had set out to expose current medical science as a ‘stupendous fraud’ and one which brought discredit on the entire medical profession. In a chapter entitled ‘Fun’ they took particular exception to the use of vivisection in the lecture theatre as a gruesome form of ‘entertainment’. The experiments on the brown dog had evoked much laughing and joking among Bayliss’s students, they asserted, and both women had observed a distinct relish with which Bayliss himself had performed the vivisection.

The jury took only twenty minutes to reach their verdict, finding for Bayliss, who was awarded damages of £2,000. In a blatant slap in the face of the anti-vivisectionists Bayliss promptly announced to the press that he was donating the £2,000 to the furtherance of physiology research at University College. Although Hageby and Schartau were obliged by the court decision to withdraw the libellous edition of the book and take out the offending chapter entitled ‘Fun’, they replaced it with a long account of the trial and quickly republished book under the new title Shambles of Science. It was reprinted four more times in the next ten years and uncensored copies of the first edition continued to be sold surreptitiously by organizations such as the Church Anti-Vivisection League.

By now, the case had ‘touched the heart of Edwardian England’. The Daily News, one of the anti-vivisectionists’ most consistent supporters among the popular press, posed the moral question now preoccupying many of its readers: ‘Is it not worth considering’, it asked, ‘whether the human race may not pay too heavy a penalty for knowledge acquired in this manner?’ Support for Coleridge, Hageby and Schartau was enormous; the fund set up by the Daily News to pay the damages was swamped with donations and exceeded within a month.

The case received unprecedented coverage, with two hundred reviews and notices appearing in the daily papers and various journals, many largely sympathetic to the anti-vivisection cause. ‘Juries are quite willing to believe that a coster can be cruel to his donkey, or a society woman to her child’ remarked one correspondent, ‘but they are very slow indeed to believe that a “man of science” can be cruel to a dog.’

One of the most unsettling aspects of the Shambles of Science case had been the extremely partisan atmosphere in court and the rowdyism of Bayliss’s medical students. Throughout the duration of the trial they queued down the Strand to obtain places in the gallery and, once in court, cheered every time a point was made in favour of vivisection. The trial is also significant in that it did much to expose the escalating tension at that time between anti-vivisectionism, feminism and medicine. At this time a significant number of suffragists were also dedicated vegetarians and animal rights campaigners, sharing a mistrust of the abuse, not just of animals, but also women, by medical men.

The fact that they lost the court case mattered little to Lizzie in comparison to the huge publicity it had attracted, contributing directly to the establishment, in 1906, of the Second Royal Commission on Vivisection, in which she took part and which sat until 1912.

Medical Experimentation on the Poor

Lizzie Lind-af-Hageby’s concerns over the abuses by medical science did not stop at animals; between 1908 and 1935 she was a member of the management committee of the pioneering Battersea Anti-Vivisection Hospital, established specifically for the free treatment of the poor and the working classes.

This institution utterly rejected vivisection in all its forms and refused to employ anyone who supported it, seeking to protect the vulnerable and especially working-class women from being used as human guinea pigs in medical trials. Years before, the anti-vivisection pioneer Frances Power Cobbe had decried the increasing over-fondness of medical practitioners for the knife and had condemned the intrusive surgical procedures made on women to control what they termed as ‘hysteria’. In similar vein Lizzie viewed with alarm the sinister transformation of many of London’s hospitals into ‘giant teaching laboratories’. As one supporter during the 1903 trial observed: ‘A poor man and a dog are exactly in the same position, in that, once in the hands of “men of science”, they are delivered over helpless, one bound in strips of list, and the other in the chains of poverty.’

In 1906, Lizzie founded her own organization – the Animal Defence and Anti-Vivisection Society – with another notable and still unsung pioneer, Nina, duchess of Hamilton and Brandon.

The two women would lead the animal rights movement in Britain throughout the interwar years, with Lizzie giving hundreds of public lectures. Herself a vegetarian, she took the realistic view that it was impossible to impose vegetarianism on the entire population. But she bravely went where few anti-vivisectors had the courage to go – into the slaughterhouses of Britain, to see conditions there for herself and lobby for improvements. As secretary of the British Section of the International Medical Anti-Vivisection Association, she was the primary instigator and organizer in 1909 of its International Anti-vivisection and Animal Protection Congress, held in London, which drew distinguished delegates from around the world.

The 1913 Libel Case

In 1912 Hageby took British citizenship at a time when tensions between anti-vivisectionists and their detractors were once more mounting. It is possible that she made this decision in order to avoid being deported for her activism. Nevertheless, a year later she was involved in another expensive libel trial, this time as the plaintiff in an exhausting sixteen-day action against the Pall Mall Gazette. The case arose as the result of an exhibition of anti-vivisection propaganda set up by Lizzie in a shop in London’s Piccadilly. It featured a window display of graphic photographs, pamphlets, extracts from Lizzie’s Royal Commission evidence, and diagrams of vivisection, accompanied by a particularly gruesome but crowd-pulling centrepiece – a stuffed dog, obtained by Lizzie after its death in a dog’s home, and mounted muzzled and on its back on a board, as had been the brown terrier dog of 1903.

In the 1913 trial Lizzie’s performance in court was nothing short of astounding. Her opening remarks alone lasted for nine hours, immediately after which she entered the witness box to give yet more lengthy evidence. So protracted was the sixteen-day trial that the Lancet complained that Miss Hageby had had more than a fair run for her money and that the case had developed into ‘something like another Royal Commission’. The judge, Mr Justice Bicknell, commended her as ‘a lady of marvellous power’ but Lizzie lost her libel action. She was, however, feted soon after at a grand vegetarian dinner held in her honour.

The Old Brown Dog Statue

It was decided after the 1903 libel case, to erect a permanent memorial to the dog that Hageby and Schartau had seen vivisected at UCL. A drinking fountain with a statue – the Old Brown Dog as it became known – was erected at the Latchmere Recreation Ground in a working-class district of Battersea by the Anti-Vivisection Society. Unveiled on 15 September 1906, it bore a plaque ‘In memory of the Brown Terrier Dog Done to Death in the Laboratories of University College in February 1903’, as well as commemorating the 232 other dogs that campaigners claimed had been vivisected in the UCL that year alone. The monument quickly became the symbol of the animal rights movement and a rallying point both for campaigners, nick-named ‘brown-doggers’, and their opponents – who were mainly medical students.

From the moment it was unveiled, medical student supporters of vivisection were determined to destroy the statue and in November 1907 a group of them, who had arrived at Battersea armed with hammer and crowbar, were involved in a scuffle with police.

For a while the monument was protected by two policemen and Battersea council hired a watchman to keep vigil overnight. The brown doggers meanwhile received widespread support from working-class activists and local trade unionists. Posters sponsored by the National Canine Defence League went up all over Battersea asking ‘Shall Battersea Lose its Brown Dog?’ in response to petitions from medical students to have it removed. The rest of that year saw a succession of riots, marches and rallies in Trafalgar Square over the Brown Dog that were widely reported in the press.

Over the next three years the two sides continued to clash in heated public meetings and debates over the statue’s removal; even suffrage meetings were heckled by medical students who associated the female animal rights protest with the wider women’s movement for the vote. The story of the Old Brown Dog meanwhile, entered into popular mythology in several songs of the time.

But by March 1910 the authorities had had enough; ignoring a petition of over 20,000 from local residents, Battersea Council demanded that the donors remove it. They refused; a year later the council removed the statue to a local municipal stoneyard where it was smashed up. In 1985 a fund-raising campaign was mounted the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection and the National Anti-Vivisection Society to replace it – and with the same inscription.

Pacifist Campaigning

Lizzie Lind-af-Hageby’s campaign for Animal rights did not stop with the Old Brown Dog. During WWI she became greatly concerned about the sufferings of animals– particularly horses on the battlefield.

In July 1915 she founded the Purple Cross Service, raising funds and subsequently setting up three veterinary hospitals for sick and wounded horses in France. After the war she continued to propagandize for peace and in several pamphlets and newspaper articles decried the harnessing of scientific discovery to the forces of modern warfare. In 1928 she warned in prescient tones of future wars where ‘poison gas and bombs of immensely destructive power will blot out whole cities in a night, long-range guns and subtle rays of death will devastate countries and mow down the people’

That same year, Lizzie was a founder of the International Humanitarian Bureau in Geneva through which she maintained close links between her pacifist campaigning and the humanitarian aspirations of her work for animals. She continued to speak out against cruel sports such as the Eton hare hunt, the use of fur and feathers in women’s clothes, fur farming and animal trapping, and the transportation of old horses to the Continent for slaughter. Together with the Duchess of Hamilton, she also established rescue units to care for wounded animals, particularly horses, caught up in the Italian invasion of Abyssinia and the Spanish Civil War. In 1954 Lizzie took over the running of the Ferne Animal Sanctuary established by the Duchess in Dorset. When she died in 1963 she left a substantial legacy of nearly £92,000 to the Animal Defence Trust.

Lizzie Lind af Hageby once wrote that ‘All humane causes are frequently taunted with having so many women among them’; in her own campaigning she made a concerted effort to overturn the hidebound perception of the stereotypical woman campaigner for animal rights as being misguided, uninformed and sentimental. She was extremely proud that so many of her sex were involved in humanitarian work, but believed that women had yet to claim and to grasp their true share in public life and social activism. Her work in all the many humanitarian causes she embraced was founded on strong Theosophist beliefs in the ‘kinship of all living creatures’. As a maternal feminist, she emphasized at all times the special bond between women working towards their own professional and educational advancement and shared the belief of many of her contemporaries that the civilizing, peace-making and – most important – humanizing influence of women would make for a better society, based on shared love and aspirations, and humane principles.

Latest Articles and Media about Queen Victoria, Prince Albert & their times

Mad Lord Adolphus, Lady Susan and Bertie’s Baby

Even Queen Victoria, who privately loved tittle-tattle but never admitted to it, could not resist being drawn into the saga of mad Lord Adolphus Vane-Tempest and his poor wife Susan…

The Curious Tale of Queen Victoria’s dresser

From Windsor Castle to North Dakota – a fascinating tale of pioneer spirit and triumph over adversity by English immigrants.

Prince Albert’s Birth: Is there any truth in the rumours of illegitimacy?

Books in English often do not have very much to say about Albert’s mother, Princess Luise of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg. Did her husband’s womanising push her into the arms of another man?

Charlotte von Siebold – the Pioneering German Midwife who delivered Queen Victoria

At the time of the future Queen Victoria’s birth, ‘the excellent Mademoiselle Siebold’ emerged from the delivery room to announce the birth of a girl to the gathered dignitaries with considerable delight, adding in her thick German accent: ‘Verr nice beebee. No big but full. You know, leetle bone, mush fat.’

Queen Victoria: Pet Names, Titles, Nicknames & Aliases

During her 63 year reign Queen Victoria acquired a wealth of these. Many were complimentary and affectionate, some were ironic or satirical, and others were downright rude…

The Victorian Christmas

The cosy Dickensian Christmas referred to in Queen Victoria’s diary for Christmas Eve 1860, was in great part popularized by Victoria and Albert after their marriage in 1840. During the 21 years that followed they did much to set their own particular stamp on how the festival is celebrated in this country.

Back Home in Dickensland

As children we were fearless. Mean, and muddy, and at times dispiriting it may have been, but the Medway Estuary was our paradise. My own daydreams draw me there still…

Sarah Forbes Bonetta: the Captive African Princess Gifted to Queen Victoria

In its Christmas Special for December 2017 the ITV series Victoria featured the story of Sarah Forbes Bonetta, a captive African princess who was brought to the court of Queen Victoria. She has frequently been described as the Queen’s goddaughter’ but this is not in fact true…

Queen Victoria’s dress sense – or lack of it

Queen Victoria’s dress sense – or rather, lack of it – was a subject that regularly provoked the despair of her courtiers. Despite his best efforts, the court painter, Franz Winterhalter, who painted some of the most fashionable women in Europe, could not disguise Victoria’s slightly provincial air…

Queen Victoria’s Passion for Photography

The 63-year reign of Queen Victoria brought with it much invention and innovation, but nothing has probably been more significant in defining the mental picture we all of have of her and Victorian everyday life than the photograph.