Back home in Dickensland

“As children we were fearless. Mean, and muddy, and at times dispiriting it may have been, but the Medway Estuary was our paradise. My own daydreams draw me there still…”

Growing up in Sight of the River Medway

The view today across the rooftops of the modest Edwardian terraced houses of lower Gillingham down to the turbid waters of the river beyond is not what it was in my childhood. Back then, I could see the funnels and masts of dozens of navy ships in port – and beyond, the marshy reaches and mud flats of the Medway Estuary. You didn’t need a clock in lower Gillingham in those days; you could time your day by the wailing midday siren that sounded off the statutory lunch hour for dockyard workers, and blared out again at 5 p.m. to mark the end of the working day (4 p.m. on Fridays). Virtually every household down our street had someone who worked at the yard; we saw the men every day toiling home up the hill on their bikes after work.

Summer holidays as a child in the 1950s were free of the sedentary electronic distractions of today; they were spent outdoors – rain or shine – running around getting dirty, scuffing knees and shoes. Our days were regularly enlivened by the thrill of seeing the tree-lined railway cutting beyond our back yard set alight by sparks from the steam trains that chundered back and forth down the service line to the dockyard. Shouts of ‘The bank’s on fire!!’ would echo up and down the street as a tribe of kids rushed out to clamber the wire fence and hang on tight watching the firemen do their work. But what we loved best was to go out roaming the sea wall beyond The Strand – the rather forlorn riverside recreation ground located next to two great Victorian gas towers on the Medway estuary not far from home.

For many local children this was the nearest they ever got to the seaside – a kind of Gillingham-on-Sea, with its murky and mildewed boating and paddling pools, its model train and swings. Many of us learned to swim here, in the no doubt polluted and certainly dangerous tidal waters of the Medway. No one in their right mind would dip even a toe in it now; in all directions today the sea wall bristles with warning signs: ‘ragged edges’, ‘slippery surface’; ‘sudden drop’, ‘deep water’ ‘unsafe for bathing’.

But as children we were fearless. Mean, and muddy, and at times dispiriting it may have been, but the Medway Estuary was our paradise. They’d told us in school, of course, all about the local connections with Charles Dickens’s ‘marsh country’. He wasn’t born here, but at Portsmouth, in 1812, but his early, happy and formative years were lived at Ordnance Terrace in Chatham and he died not far away in 1870 at his beloved home Gad’s Hill Place at Higham – where, long after, local people ‘still felt the miss of him’, as they put it. The surrounding area held an important place in Dickens’s creative imagination: there was and remains something about the ineffable bleakness of the salt marshes and mud flats stretching for miles along the ancient Saxon Shore that lured him, as he remarked in a piece in The Uncommercial Traveller:

‘There are small out of the way landing-places on the Thames and the Medway, where I do much of my summer idling. Running water is favourable to day-dreams. And a strong tidal river is the best of running water for mine.’

My own daydreams draw me there still. The abandoned Hoo and Darnet Forts built on a couple of islands a short distance out into the estuary in 1871 as sea defences for the Royal Dockyard were tantalising; one summer my twin brothers and I made a secret trip out there in our precarious, homemade dinghy, to the horror of our parents. And then there was the long expanse of the sea wall to Sharp’s Green, Horrid Hill and Motney Hill beyond, where I roamed happily with school friends on hot summer days, camping out by the water’s edge and frying eggs on a primus stove. No parent would allow an eight year old to venture there now – but we did (despite the occasional wagging fingers warning of ‘dirty old men’ lurking in the bushes). We went there often and freely, to sit and watch the ships in the estuary, clamber over the huge concrete anti-tank placements along the beaches – a still lingering vestige of World War Two – and imagine ourselves as intrepid and adventurous as the Famous Five – only no turkey sandwiches and ginger beer for us – they were posh and we were poor.

Charles Dickens’s ‘Marsh Country’

My childish imaginings of the mythical Dickensland I knew of from abridged versions of his novels read at school found its incarnation in the wonderful rambling old vicarage garden and parish churchyard of St Mary Magdalene up the hill from The Strand, with its tumbledown grave stones and old Victorian gas lamps lining a walkway of great chestnut trees. It was perfect for games of hide and seek and always made me think of the overgrown garden at Miss Havisham’s. Equally spooky was the little church on the marshes at Cooling; the little grey, Kentish ragstone lozenges covered in lichen, marking the graves of the infant children of the Comport family of Cowling Court which were the inspiration for the opening scene in Great Expectations.

Closer to home was the still familiarly Dickensian High Street in Rochester with its old coaching inn, The Bull, where once legendary haunches of venison, saddles of mutton and ribs of beef were enjoyed with such relish by Mr Pickwick and his companions.

Further down the north Kent coast, where we went for Sunday outings in dad’s old black van, was the fishing port of Whitstable with its famous oysters, so beloved by Dickens.

Furthest away, on the periphery of my own Kentish childhood landscape, lay the white cliffs of Dover where David Copperfield first encountered his aunt Trotwood, a scene ingrained in my mind by endless TV showings of George Cukor’s 1935 film version of the book. The landscape of Dickens’s novels were all around me; they were subsumed into my subconscious, inspired my reading and in the end my development as a historian and writer with a passion for the Victorian period.

The Last Days of Chatham Dockyard

In 1984 everything changed in the Medway Towns that I knew when they closed the Dockyard and thousands of men were thrown out of work, my shipwright brother among them. The demise of the great naval tradition at Chatham and with it the ruthless destruction of the livelihoods of generations of highly skilled craftsmen sounded the death knell of a once thriving and proud area that had been rooted in a centuries-old naval tradition.

A long slow descent into decay and dereliction followed over the next twenty years. Lower Gillingham, never a pretty place even in my childhood, was virtually eviscerated of all its character. Its High Street became a soulless pedestrianised precinct of pound shops, nail and tattoo parlours, charity shops and market stalls selling cheap tat. The branch of David Greig’s the grocer’s with its cool marble and majolica tiled interior, where as a child I used to watch the assistants expertly cut and shape the great mounds of butter with wooden butter pats is now a building society. The old Victorian houses of the original working-class community along the river have long since been demolished and with them the spit and sawdust dockworkers’ pubs that stood on every corner.

Snapshots Of The Past, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

With the ships long gone and only commercial traffic out on the river, it was some time before eighty acres of the original vast dockyard site were redeveloped. The most attractive eighteenth-century buildings were refurbished as the Chatham Historic Dockyard, while the remaining 320 acres have by degrees risen from the ashes as a mix of commercial port, shiny new apartment blocks, a posh marina and shopping centre – with further major development still to come. From my old bedroom window the open view to the marshes of the estuary that I so loved is now blocked by the shiny new buildings of the Medway campus of the University of Kent.

In 2012, his bicentenary year, the traditional links with Charles Dickens brought a resurgence of interest in this once proud but still economically depressed part of north Kent. Taking centre stage in the old Chatham docks – a stone’s throw from the original Cashier’s Office, where Dickens’s father John worked as a navy pay clerk for the Admiralty from 1817 to 1822 – a garish new Dickens World has been opened to celebrate the area’s ‘local boy’. It is however geared not so much to a serious celebration of the literary legacy of the man as to the popular, tabloid image of Dickens and his world, which can be experienced in an indoor street cum theme park of ersatz Dickensian shop fronts that looks like the film set of Oliver! and which is populated by out of work actors in costume hamming it up as Dickens characters.

Despite the long periods he lived in London and abroad between 1824 and his return to Kent in 1860, we have always felt that Dickens belongs to us here, on the Medway; for as his biographer John Forster said, Kent was ‘the birthplace of his fancy’. Dickens spent his honeymoon at Chalk, near Gravesend, and some of the great moments of his novels are rooted in the county: from Mr Pickwick’s Rochester in his first, 1837 novel, to the dramatic and chilling encounter between Pip and the escaped convict Magwitch on the marshes in the opening pages of his 1861 work Great Expectations; to his final novel, left unfinished in 1870, where Rochester brings Dickens the writer full-circle with The Mystery of Edwin Drood, set in the gatehouse and precincts of the cathedral.

Having long known and loved Gad’s Hill Place, a house seven miles out of Rochester that he had seen on his walks around the Hoo Peninsula, Dickens was able to purchase it in 1856 for £1,790 and spent much of the last ten years of his life there. After his death in June 1870 the house eventually passed out of the Dickens family and in 1924 became a private day school. It opens to the public on the first Sunday of the month from May to October.

Restoration House, the inspiration for Miss Havisham’s Satis House, is located in Crow Lane a short distance from the cathedral in Rochester; a fine Elizabethan building, it is as evocative as ever and although in private hands can be visited on Thursday and Friday afternoons between June and September.

When my parents were alive and I visited them in Gillingham, the nostalgia for the lost innocence of my childhood and the Dickensian world that captured it always tugged at me, prompting me to head for river. Dickens relied on the landscape around him – whether urban or rural – as an important outlet for his restlessness. He often walked along the reaches of the Hoo Peninsula in sight of the Thames and Medway Estuaries on either side. To do so allowed him valuable thinking time in which to refine the characters and plotlines that crowded his overactive imagination. Most of the long, flat uninterrupted horizontal line of the river survives only in the descriptive passages of his novels now.

Today the horizon is dominated by the cooling tower of the Kingsnorth oil refinery on the Isle of Grain. But we do still have the Saxon Shore Way that Dickens knew and loved and walking along it today, in sight of the river and the marshes that held such an important place in the great writer’s psyche, one can still sense his spirit – a man determinedly striding out, stick in hand, head up into the wind off the water, with the cry of the seagulls and plovers above him.

Latest Articles and Media about Queen Victoria, Prince Albert & their times

Mad Lord Adolphus, Lady Susan and Bertie’s Baby

Even Queen Victoria, who privately loved tittle-tattle but never admitted to it, could not resist being drawn into the saga of mad Lord Adolphus Vane-Tempest and his poor wife Susan…

The Curious Tale of Queen Victoria’s dresser

From Windsor Castle to North Dakota – a fascinating tale of pioneer spirit and triumph over adversity by English immigrants.

Prince Albert’s Birth: Is there any truth in the rumours of illegitimacy?

Books in English often do not have very much to say about Albert’s mother, Princess Luise of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg. Did her husband’s womanising push her into the arms of another man?

Charlotte von Siebold – the Pioneering German Midwife who delivered Queen Victoria

At the time of the future Queen Victoria’s birth, ‘the excellent Mademoiselle Siebold’ emerged from the delivery room to announce the birth of a girl to the gathered dignitaries with considerable delight, adding in her thick German accent: ‘Verr nice beebee. No big but full. You know, leetle bone, mush fat.’

Queen Victoria: Pet Names, Titles, Nicknames & Aliases

During her 63 year reign Queen Victoria acquired a wealth of these. Many were complimentary and affectionate, some were ironic or satirical, and others were downright rude…

The Victorian Christmas

The cosy Dickensian Christmas referred to in Queen Victoria’s diary for Christmas Eve 1860, was in great part popularized by Victoria and Albert after their marriage in 1840. During the 21 years that followed they did much to set their own particular stamp on how the festival is celebrated in this country.

Sarah Forbes Bonetta: the Captive African Princess Gifted to Queen Victoria

In its Christmas Special for December 2017 the ITV series Victoria featured the story of Sarah Forbes Bonetta, a captive African princess who was brought to the court of Queen Victoria. She has frequently been described as the Queen’s goddaughter’ but this is not in fact true…

Queen Victoria’s dress sense – or lack of it

Queen Victoria’s dress sense – or rather, lack of it – was a subject that regularly provoked the despair of her courtiers. Despite his best efforts, the court painter, Franz Winterhalter, who painted some of the most fashionable women in Europe, could not disguise Victoria’s slightly provincial air…

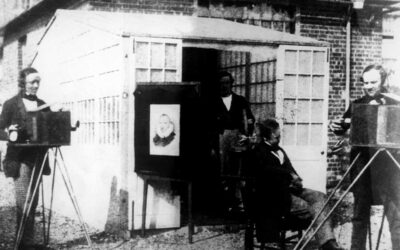

Queen Victoria’s Passion for Photography

The 63-year reign of Queen Victoria brought with it much invention and innovation, but nothing has probably been more significant in defining the mental picture we all of have of her and Victorian everyday life than the photograph.