From Windsor Castle

to North Dakota

The curious tale of Queen Victoria’s Dresser

Marie Downing Williams

“From the first I liked the immensity of sky and prairie and even though I sometimes was lonesome in the early days when we had so few

neighbors, I never wished to return to England or to the luxuries of the life I had formerly lived.”

MARIE DOWNING WILLIAMS

An abandoned North Dakota farmhouse

A fascinating tale of pioneer spirit and triumph over adversity

In August 1930 a fascinating tale of pioneer spirit and triumph over adversity by English immigrants to the American Midwest appeared in the Winnipeg Free Press. It was quickly syndicated across the USA, headlined ‘From Windsor Castle to Prairie Farm’, and told the ‘romantic story of a maid-in-waiting to Queen Victoria who became a farmer’s bride, cutting hay and pitching sheaves’ on a remote North Dakota homestead.

I discovered the fascinating story of Marie Downing Williams quite by accident when doing some research on Queen Victoria’s dressers. I had compiled a list of the better-documented ones, but had not yet found more than a name for Marie Downing and her service to the queen. The story she told in an extensive interview given for the article intrigued me, but it also threw up many questions. This is how Marie told it to reporter Barbara Babcock McCahren in 1930:

She began with an evasion: not stating when or where she was born or anything about her background; press stories would give her birth date as around 1853, but we shall return to this later. Marie’s account dives straight into the 1880s and how having obtained a position of trust at court as one of Queen Victoria’s favourite dressers and most trusted attendants, she was persuaded by her sweetheart Harry Williams to give it up for life as a poor farmer’s wife ‘beyond the outposts of civilization’ in North Dakota.

All Marie had to say about her early life was that she had started out as ‘an apprentice in a sewing shop that made garments for the Queen and her children’. One day when Marie was delivering finished garments to Windsor Castle for a fitting, Queen Victoria had ‘asked her how she would like to enter her service as a personal attendant’. Marie accepted with alacrity and, she claimed, spent eight years with Victoria, receiving no salary, but ‘generous gifts of jewels’ and other items in return for her services. Hm …

There is no doubt that Marie did, genuinely, work for Queen Victoria as a dresser, as I will explain later. There is also an intriguing part of her early story that can be substantiated, relating to how, in 1880, Queen Victoria ‘loaned’ Marie to her friend and fellow widow, the exiled Empress Eugenie, at a time when Eugenie was desperately in need of emotional support. Marie was enlisted that March to act at Eugenie’s companion and dresser on a sad and solemn pilgrimage to the place in Southern Africa where her adored only son the Prince Imperial had been killed in a skirmish during the 1879 Zulu War. It was a difficult journey, and not without its dangers as they travelled into the interior and camped on the veldt. Marie had to deal with the empress’s very profound grief and brooding silence, as well as her refusal to eat. At times she feared that Eugenie’s mind ‘might become deranged’. Marie was convinced that it was only her presence that saved her from suicide. Having seen the site where her son was killed, Eugenie generously rewarded Marie for her devotion.

The Sweethheart, the Queen & the Homestead

Continuing with her story, as told in 1930, Marie related how Queen Victoria, like Eugenie, held her in high regard and presented her with numerous gifts, such as a beautiful watch as a ‘form of rebuke’ after she had once arrived late on duty. Indeed Victoria valued Marie so greatly that she apparently twice refused her permission to leave her service. Marie wanted to marry her sweetheart Harry Williams, but women of the Royal Household could not marry without the queen’s permission and dressers were normally single women or widows. Undeterred, as Marie related, she and Harry went ahead and married in secret. But she didn’t say where or when. I searched and searched but drew a complete blank.

By 1882 Harry had become restless with life in service as a butler and was eager to seek his fortune in the New World. And so he set off for Manitoba in Canada to stake a claim to a homestead, the intention being that Marie would follow him out there as soon as she could extricate herself from the Queen’s service. But the 160 acres of land Harry was granted at Shilo were poor in quality and he upped sticks and travelled 150 miles south across the border to Rolla in North Dakota. In 1885, under the Homestead Act, he filed for a plot of land southwest of Rolla in Maryville Township.

Finally, Marie was able to persuade the queen to let her go and she sailed from Liverpool on the SS Gallia, a Cunard Line steamship then popular with emigrants to America.

She later said she arrived 28 December 1886 but this cannot be right – the only sailing for the Gallia that fits is one for 1887 that arrived in New York on 27 December. And now comes the most bizarre part of Marie’s story: on landing in New York and reclaiming her luggage, Marie was told, much to her surprise, by the customs inspectors at the port that ‘I had several more trunks than I claimed. Upon investigation I discovered the trunks were all labeled with my name and I knew that Her Majesty had sent them.’ The queen, it would appear, ‘had made sure that her favored maid-in-waiting should have many reminders of the regal days she had left behind her.’ Hm …

Marie’s recall might be faulty on some things but she never forgot the long and arduous train journey from New York to the bleak, snow-covered plains of the Dakota Territory in the dead of winter; it had been ‘much more terrifying than her trip with the Empress Eugenie to South Africa’. Harry was there to meet her on 1 January (Marie said 1887 but it must have been 1888) when she arrived at Minnewaukan, the terminus of the recently completed Northern Branch of the North Pacific Railroad.

“…in a temperature of -40 degrees F below, Marie shielded her face from the biting wind with a dainty English parasol from the trunk of gifts sent by Queen Victoria”

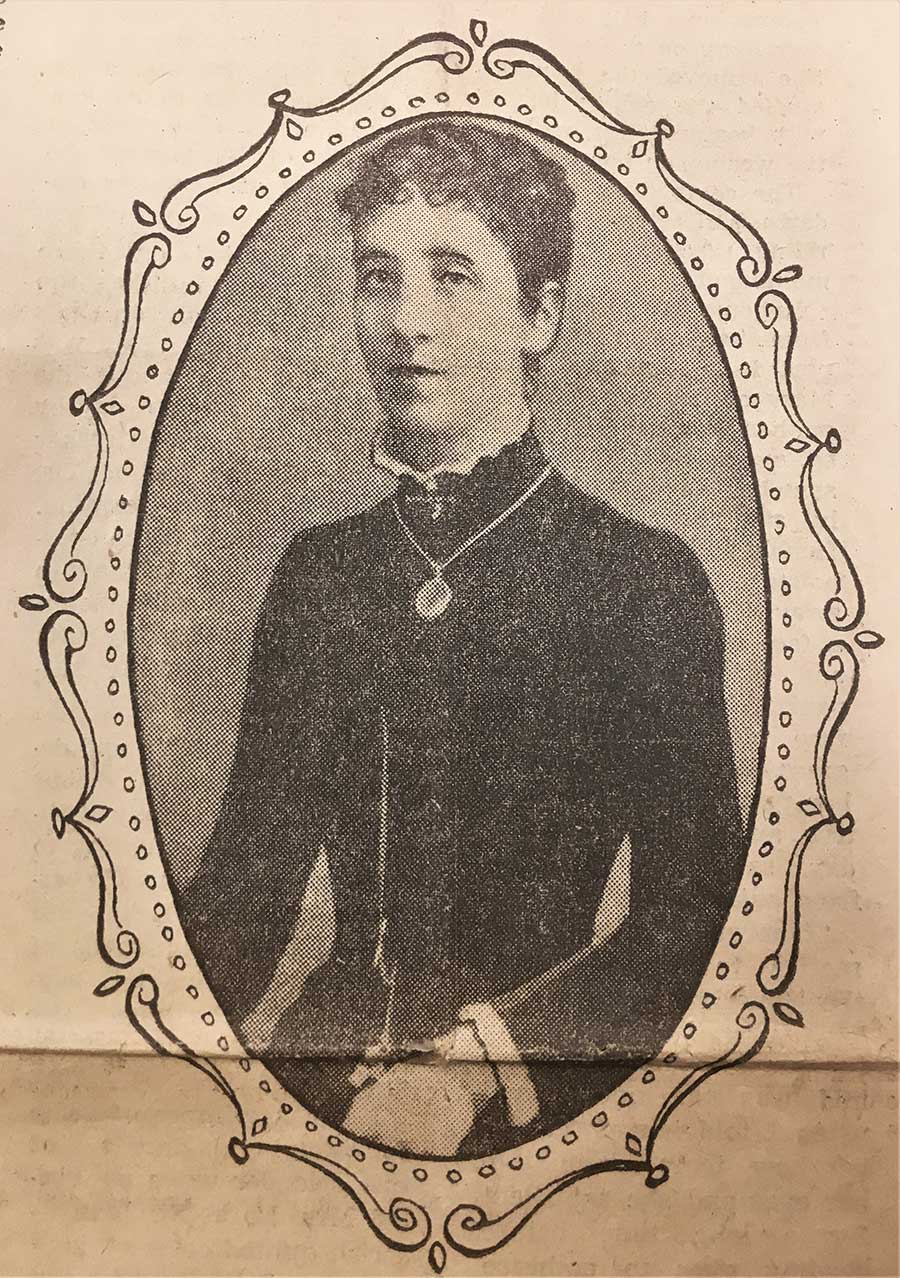

Located at Devil’s Lake, the railroad stop at Minnewaukan was more than 100 miles from the little town of Rolla and the homestead nearby that Harry had been having built for them. They had to take the mail sleigh across the frozen lake in a temperature of -40 degrees F below, with Marie shielding her face from the biting wind with a dainty English parasol from the trunk of gifts sent by Queen Victoria. But first, she and Harry went straight to the local frontier minister to get married – Marie claiming that a condition of her release from Victoria’s service had been that she would immediately send the Queen confirmation that she had married Harry on arrival. The English clothes she had travelled in proved totally inadequate for the brutal weather that greeted her. A kind-hearted local shop keeper lent Marie a thick raccoon coat, several sizes too large, for the wedding ceremony – seen in this grainy surviving photo – although one fanciful account I found talked of it being ‘a beautiful brocade lined mink coat given her by the queen before she left’!

It took two days for Marie and Harry to get to the rudimentary, one-roomed log cabin at Rolla that was to be their home, by open wagon in the perishing cold. The 160-acre smallholding was buried in deep snow, the cabin only had half a roof and the doors and windows were not yet in. Marie seemed to take it all in her stride, despite the culture shock after life at Windsor. Neighbours put them up until work was finished on the cabin, but life thereafter was incredibly tough. Marie learned how to drive a team and stack the wheat; once when Harry was ill, she mowed one hundred tons of prairie hay on her own. Rolla in the 1880s was a typical midwestern one-horse town set in a bleak, flat landscape – the kind in which only the most intrepid of emigrants would have wished to settle. Despite all the hardships, she came to love life on the frontier:

‘From the first I liked the immensity of sky and prairie and even though I sometimes was lonesome in the early days when we had so few neighbours, I never wished to return to England or to the luxuries of the life I had formerly lived.’

Embellishing the Truth?

But life in this social backwater was quickly enlivened by Marie’s tales of her time in royal service, as she opened the trunks and produced her royal treasures to show to her friends: dresses, silks, laces, nightgowns of Irish linen with Victoria’s monogram, tablecloths, and silver cutlery, to name but some of them. The young bride from England became ‘the belle of the community in the eighties and nineties, with her gowns of heavy silk, elaborately embroidered and beautifully fitted’. But what possible use would such extravagant clothing have had on the American frontier, other than to impress, or to sell for hard cash to keep the farm going? The Queen’s gifts certainly came in handy with money perennially short; bit-by-bit some were sold to buy farmland or were ‘forfeited to pay for the meagre necessities of life on the Dakota frontier’. Other items went to pay medical costs or to satisfy the vanity of local ladies with a bit of money who wanted to own something that had once belonged to Queen Victoria or Empress Eugenie – for Marie had also acquired several gifts from the French Empress during her time with her. But would Queen Victoria really have sent Marie ‘an elaborate gold-mounted saddle’ for use in that rough and ready place when she apparently wrote and told her she had no saddle for the horse? Hm …

Victoria’s ‘favourite attendant’

Marie clearly enjoyed her celebrity as Victoria’s ‘favourite attendant’, entertaining guests dressed in the tight corseted gown in which she had last attended the Queen in the small living room of her home, its walls hung with portraits of the royal family. She was particularly proud to show off her seal ring engraved with her initials; the queen had ‘designed the ring for her so that she could re-address the queen’s mail when need of secrecy was imperative in state and foreign communication,’ Marie explained. ‘This ring was used to seal the envelopes.’

And then there were the various jewels that Marie had sewed into various headdresses and gowns for the Queen, which Victoria had then presented to her; not to mention those given her by Empress Eugenie. These were the first to go when times were hard or Harry needed more land to farm or more horses. Marie clearly had no sense of their true market value and sold the diamonds and other jewels for well below the going price. A diamond brooch presented to her by Eugenie was sold to Governor Burke of North Dakota for his wife, as too some diamonds from a tiara owned by the French empress. As for the queen’s gowns – Marie occasionally wore them to show off to visitors or even loaned them to the ladies of Rolette County for special occasions and even weddings. Some were sold, others simply given away or lost, but one – a dress worn by Queen Victoria for a Garter ceremony – survives today in the Prairie Village Museum in Rugby, North Dakota.

Another survival, in the State Historical Collection at Bismarck is an ivory backed mirror in a velvet lined leather case. Accompanying this item is a letter from Marie to Mrs Burke, the Governor’s wife, who acquired it, detailing its provenance as a gift from Queen Victoria. It shows a cultured and literate hand – and an extravagant monogram on Marie’s writing paper:

When settler life in North Dakota finally became too hard Marie and Harry leased out their farm and in 1909–10 made a return visit to England. When they got back they ran a boarding house where they served their guests with ‘the queen’s solid silver cutlery’. In the Rolette County scheme of things they became ‘prominent people’, taking American citizenship in 1890. Harry served as a magistrate and member of the local Masonic Lodge, but they never enjoyed financial prosperity for long.

That much is the story, as told across numerous variant articles, in 1930. But the more I delved into Marie’s account, with the help of Stephanie Steinke, Executive Director at the Prairie Village Museum, the more frustrated we became with the many contradictions and questions that it raised.

First and foremost, neither of us could find any trace of a birth for a Marie Downing, Stephanie in particular having searched hard for years to find her. Harry had said she was born in Ipswich in 1853 but there was no sign of her there. It struck me early on that Marie had disguised who she was, perhaps in order to obtain a decent job in service and that later, in North Dakota, had perpetuated a few self-created myths, if not porkies, about her royal connection, on which she clearly dined out for many years.

I spent hours searching for clues to her true identify, and finally found what I was looking for: a brief and superficially inconsequential cutting about the death of her husband Harry in 1940 published in the local Rolla newspaper, the Turtle Mountain Star (what a name!) on 28 March. In it Harry named his late wife as Miss Marie W. C. Downing.

Any family historian will tell you that middle names are the most crucial deciding factor in identifying someone with a fairly common name, even when they are only initials. Importantly, the 1940 article confirmed that Marie really was Marie and not Maria or Mary, as other sources had named her. At last I had something I could work on. Diligent searching on Ancestry.co finally brought me to the real woman.

She was baptised Maria Woods Crook, the illegitimate daughter of Rebecca Crook and William Woods an agricultural labourer, at Snetterton in Norfolk on 7 March 1846, having been born on 23 December 1845. Harry got the day and the month right in later interviews but never seemed to know his wife was eight years older than any sources had till then suggested.

It’s not clear at what point she started calling herself Marie, but she acquired the surname Downing through her stepfather, when Rebecca Crook married John Downing in 1854. A couple of sources claimed that Marie’s birth father William Woods had worked with horses, as a stable hand at Windsor Castle. The name is unfortunately too common to be certain, but there is a William Woods listed in the Royal Mews in the 1850s. By the time of the 1861 census 14-year-old Maria Woods Crook was working as a servant in Diss, 15 miles from her birthplace. I couldn’t find her on the 1871 census and she is not listed under the Department of the Mistress of the Robes in the 1878 and 1879 editions of the Royal Kalendar, where Queen Victoria’ chief dresser was the long-serving Emilie Dittweiler.

Harry, who was born in Brant Broughton Lincolnshire in 1854, by the 1871 census was working as a footman at the manor house of a local farmer. By 1881 he had been elevated to butler at the home of Edward Vickers, a retired steel manufacturer near Stratford on Avon (from the famous family of British industrialists). (In his own later account Harry also appeared to have been presented with a carpetbag full of ‘gifts’ by his grateful employer Mr Vickers, which he said was stolen when he arrived in Canada).

The first thing I was delighted to be able to substantiate when I had Marie’s real name was her original secret marriage to Harry. Marie Woods Crook (though she confuses his surname) aged 27 married Henry Williams (24) at Rugby Register Office on 13 February 1880 by Special Licence. Harry’s father is described as a groom but the story as told in the 1930s was that it was Marie’s!

Why they married at Rugby I cannot tell, but the licence adds to the air of haste and secrecy; for barely two months later Marie left Southampton for the Cape of Good Hope with Eugenie.

I haven’t been able to figure out where and when Harry and Marie first met, though there is an intriguing link. In a later interview Harry claimed to have been sometime butler to Sir Arthur Bigge, a notable member of the Royal Household, later elevated to Baron Stamfordham. Although I have found no evidence to confirm Harry’s employment with him, Bigge served in the army on the staff of Sir Evelyn Wood in Southern Africa. In fact, Bigge was a close friend of the Prince Imperial and witnessed his death. He helped organize Empress Eugenie’s journey to South Africa in 1880 to recover his body, and in 1881 was appointed equerry in ordinary to Queen Victoria. Crucially, Queen Victoria confirms this in her journal for 1 June 1881:

‘The sad and terrible anniversary of the poor Prince Imperial’s death. Wrote and telegraphed to the dear Empress, who spent the day last year in Zululand, on the very spot where he was killed. Strange to say, 2 of those, who were with her then, are here with me now, Capt. Bigge, & Mary [sic] Downing, her maid, who came to me, some little while ago.’

This journal entry clearly contradicts Marie’s story: far from being in the Queen’s service ‘for eight years’ i.e. since the 1870s, she in fact had not long joined Victoria. She first appears in the Royal Household index in 1882; in April 1881 she is on the census at Windsor Castle – as Marie Downing aged 29 (when in fact she was 35) – and disguising her married status. She is listed as a Queen’s Dresser along with Emilie Dittweiler and Elizabeth Morgan. It is also interesting to note that Harry, as Bigge’s butler might have accompanied him to Southern Africa in 1880 – (although he is employed by Edward Vickers by the time of the 1881 census).

Did Harry and Marie therefore both sail to Capetown in Empress Eugenie’s entourage – as an already secretly married couple?

It would seem from this time frame and the Queen’s journal that Marie must have been in service to Empress Eugenie before joining Victoria, rather than the other way round, as given in all newspaper accounts. A photograph of her in 1877 was supposedly taken at Carlsbad when she was travelling in Europe with Eugenie. I cannot find Marie on census night 1871 although the recently exiled Eugenie and her husband, former Emperor Napoleon III, are listed at home in Camden Place Chiselhurst.

The Missing Years

So where was Marie between the 1861 census and Windsor in 1881? There is no contradicting the actual record held at the Royal Archives, as confirmed to me by Senior Archivist Julie Crocker: ‘Marie is recorded as a Dresser to Queen Victoria from approx. 1881 until 1885, when she was granted a pension by the Queen.’ And here we encounter another anomaly. Marie did not leave for America till 1886 or 7 but from this it would appear that she left the Queen’s service a year or so prior to that. In fact, a letter of 1 June 1886 that Marie wrote to the Duchess of Buccleugh – then Mistress of the Robes and in charge of the royal dressers – infers that Marie might have been dismissed. In it she talks of her difficulties in finding employment and advises the duchess of her intentions to marry a man in America.

But hang on: the inference here is that Marie had already left royal service before mentioning her marriage. This of course does not square with her claims about begging to be released from service and being refused because the Queen valued her so much. The Royal Archives informed me that normally any pension received would cease on marriage but from another letter Marie wrote on 6 June, it appears that Victoria had made an exception in her case, and agreed the pension would continue. Harry later confirmed she received $60 every quarter from Windsor. One wonders why this concession was made, especially if Marie left under a cloud.

And what about the duplicate certificate for her second marriage that Marie supposedly sent to Victoria from Devil’s Lake? There’s no sign of it in the RA and the original Minnewaukan records were lost to fire and water damage some time ago. Nor is there any note in the RA of Marie’s claim that the queen wrote a personal cheque for her to buy her ticket on the Gallia to America, or indeed any proof that she and the Queen ever directly corresponded.

In any genealogical record there are always going to be contradictions and inconsistencies: names, dates and places often get muddled. There are, in particular, considerable discrepancies over Marie’s correct age. One cannot be certain of the mental clarity of someone telling their story much later in their seventies and Marie and Harry may well have muddled things in their accounts. But there are also times when both appear evasive about the true provenance of the extraordinary accumulation of items supposedly ‘given’ to Marie by Queen Victoria, and no one in Rolla ever seems to have challenged the legitimacy of her ownership of them.

The Big Question Mark Hanging Over the Story

Like it or not, one has to ask the question: did Marie slowly and systematically purloin some of those ‘gifts’ from Victoria, and Eugenie too for that matter? The Queen was certainly not ungenerous and there are ample records of items of jewellery, pieces of lace, shawls and dresses made to various ladies in her entourage, particularly those who served her for many years. But trunkloads? Sent all the way to New York? To a woman who was with her for only about 4-5 years? It simply does not stack up. Why would such things be given to a former dresser who was heading for the back of beyond to live on a homestead on the American frontier? What use would Marie Downing have for a ‘court train six yards in length’ that Queen Victoria had worn at state functions; or an inlaid Egyptian marble paperweight; or a black parasol lined with purple satin (all gifts, along with various items from Eugenie, at one time or another mentioned in press articles about Marie). This is the big question mark hanging over her story.

Whatever the truth, Mrs Harry Williams as she was then generally called, spent her final years in a modest little house in Rolla after she and Harry sold the farm, always ready to dress visitors up in Victoria’s gowns and impress them as a ‘brilliant conversationalist’.

She and Harry never had any children. Marie died on 5 December 1933; Harry outlived her by seven years. If you seek out their grave today you will have a hard time finding it. In the old cemetery half a mile out of Rolla they lie in a plot owned by their friend and beneficiary Anna Lo. Mrs Lo never learned to read and write and so the inscription on their grave simply reads ‘The Williamses’.

Queen Victoria’s black garter dress is now on display at the Prairie Village Museum. A few other items found their way to a relative in Canada, such as this gold locket, (now in the Canadian Museum of History), containing what might be photographs of Marie as child and young woman. Is this the same locket that she is wearing in the photograph supposedly taken in Carlsbad in 1877 when Marie was in service to Empress Eugenie? I wish I knew for sure.

I would be delighted to hear from any readers who can fill in any of the gaps in this intriguing story. Meanwhile, my thanks to Stephanie Steinke, Executive Director of the Prairie Village Museum in Rugby, North Dakota for her invaluable input and enthusiasm.