Victoria, Albert & their Patronage of Photography

“Such was Victoria’s compulsion for collecting family photographs that they eventually took up every inch of space in her cluttered private rooms at Windsor, Osborne and Balmoral.”

A Royal interest

The 63-year reign of Queen Victoria brought with it much invention and innovation, but nothing has probably been more significant in defining the mental picture we all of have of her and Victorian everyday life than the photograph.

In England, William Henry Fox Talbot had developed his own negative-positive photographic process in the late 1830s, independently of the experiments in France at the same time made by Louis Daguerre. By 1839 the first daguerreotypes were being imported into Britain from France, but it was not until March 1841 that the photographic portrait – then still a rarity – was made available to the public, when Richard Beard bought the patent rights and set up a daguerreotype studio in London. Soon after, one of Daguerre’s pupils, Antoine Claudet, established his own studio in London, having already presented the Queen and Prince Albert with a selection of his images of European cities a couple of years earlier.

Victoria and Albert had become aware of Fox Talbot’s work as early as 1840, thanks to the efforts of Talbot’s half-sister Caroline, who had been appointed a lady of the bedchamber to the Queen that year. At Windsor Castle, early in August, Caroline had showed an album of her brother’s work to the royal couple. She was delighted with their response, telling her mother that ‘Prince Albert has a great knowledge of the Arts & thinks your discovery will be of great consequence to them.’

“That first sight of the Talbot album in 1840 no doubt tapped into an early interest taken in photography by Prince Albert that had not needed any encouragement. In fact, as the Queen recorded in her journal, she had shown Albert some daguerreotypes recently sent to her from France on the very day – 15 October 1839 – when she had proposed marriage to Albert.”

The First Photgraphs of Victoria & Albert

An early photo of Queen Victoria – 1844

Patronage of William Edward Kilburn

In April 1847, the English daguerreotypist William Edward Kilburn, who had set up a studio in London’s Regent Street, was commanded by the Queen to make the first daguerreotype portraits of herself, Prince Albert and their children, which were taken in the conservatory of Buckingham Palace. Such a sought-after commission and Kilburn’s almost immediate appointment as ‘Photographist to Her Majesty and His Royal Highness Prince Albert’, led to his rise as a leading daguerreotypist of his day. Of particular significance in the history of photography is the fact that Kilburn took what is thought to be one of the earliest crowd scenes – of the huge Chartist rally held at Kennington Common in London in April 1848. The photograph, long presumed to have been lost, was rediscovered in the in the Royal Collection in the 1980s, a testament to the considerable acumen of the royal couple as collectors.

Many of the first domestic photographs of the royal family were in fact not taken by professionals, but by Prince Albert’s librarian, Dr Ernst Becker, assisted by one of his equerries, Captain Dudley. The Queen and Prince Albert both learned the early Calotype and Talbotype techniques of printing – known as the ‘black art’ because of the staining this produced on the hands – and certainly produced some of their own photographs, although none of these seem to have survived. They would, in the main, confine themselves to collecting rather than taking photographs, leaving the passion for photography as a hobby to be embraced by their children –– in particular the Prince of Wales, Prince Alfred, Prince Leopold and Princess Beatrice.

Photography featured at the Great Exhibition of 1851

Prince Albert & Crimean War Photographer Roger Fenton

Through their patronage of the Royal Photographic Society, as it later became known and to which they donated money for the furtherance of photographic techniques, Victoria and Albert met the pioneer photographer Roger Fenton, who was invited by them to set up a dark room for the prince at Windsor in 1854. Prince Albert greatly admired Fenton’s work, and encouraged him to travel to Crimea during the war of 1854–6 to take what would be the first photographic experiments in photojournalism. With an eye to posterity, Albert astutely commissioned Fenton to take 300 or more portraits of British soldiers and officers – many of them mutilated by their wounds, as a documentary record. He also commissioned several carefully composed and sanitised views of the battlefields– which were exhibited at the Royal Photographic Society’s first exhibition in London in 1855.

The Crimean War collection would be but one example of the prince’s keen interest in the photograph’s development, as an important historical document and teaching aid, and the scrupulous and systematic method which he adopted in mounting and cataloguing such photographs ensured that they would be preserved for posterity. From the 1850s he also set in motion an ambitious project to make photographic reproductions of the priceless drawings by his favourite artist, Raphael, held in the Royal Collection and other repositories.

Crimean War photographer Roger Fenton in his waggon

Collectors of Photography as Art

1848 hand tinted daguerreotype of Prince Albert

The Rise of the Carte de Visite

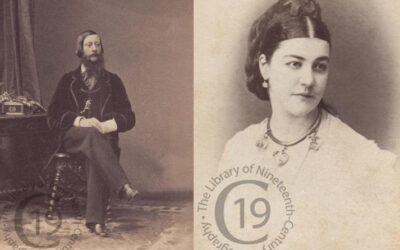

Group photograph of (from left to right) Prince Philippe, Count of Flanders; Prince Albert, Prince Consort; Princess Alice; Infante Luís, Duke of Porto, later King Luís I of Portugal; Queen Victoria; Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII; and King Leopold I of the Belgians; 1859

Latest Articles and Media about Queen Victoria, Prince Albert & their times

Mad Lord Adolphus, Lady Susan and Bertie’s Baby

Even Queen Victoria, who privately loved tittle-tattle but never admitted to it, could not resist being drawn into the saga of mad Lord Adolphus Vane-Tempest and his poor wife Susan…

The Curious Tale of Queen Victoria’s dresser

From Windsor Castle to North Dakota – a fascinating tale of pioneer spirit and triumph over adversity by English immigrants.

Prince Albert’s Birth: Is there any truth in the rumours of illegitimacy?

Books in English often do not have very much to say about Albert’s mother, Princess Luise of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg. Did her husband’s womanising push her into the arms of another man?

Charlotte von Siebold – the Pioneering German Midwife who delivered Queen Victoria

At the time of the future Queen Victoria’s birth, ‘the excellent Mademoiselle Siebold’ emerged from the delivery room to announce the birth of a girl to the gathered dignitaries with considerable delight, adding in her thick German accent: ‘Verr nice beebee. No big but full. You know, leetle bone, mush fat.’

Queen Victoria: Pet Names, Titles, Nicknames & Aliases

During her 63 year reign Queen Victoria acquired a wealth of these. Many were complimentary and affectionate, some were ironic or satirical, and others were downright rude…

The Victorian Christmas

The cosy Dickensian Christmas referred to in Queen Victoria’s diary for Christmas Eve 1860, was in great part popularized by Victoria and Albert after their marriage in 1840. During the 21 years that followed they did much to set their own particular stamp on how the festival is celebrated in this country.

Back Home in Dickensland

As children we were fearless. Mean, and muddy, and at times dispiriting it may have been, but the Medway Estuary was our paradise. My own daydreams draw me there still…

Sarah Forbes Bonetta: the Captive African Princess Gifted to Queen Victoria

In its Christmas Special for December 2017 the ITV series Victoria featured the story of Sarah Forbes Bonetta, a captive African princess who was brought to the court of Queen Victoria. She has frequently been described as the Queen’s goddaughter’ but this is not in fact true…

Queen Victoria’s dress sense – or lack of it

Queen Victoria’s dress sense – or rather, lack of it – was a subject that regularly provoked the despair of her courtiers. Despite his best efforts, the court painter, Franz Winterhalter, who painted some of the most fashionable women in Europe, could not disguise Victoria’s slightly provincial air…