Prince Albert: Is there any truth in the rumour of illegitimacy?

“Although at times bewildered by her husband’s selfish behaviour and abandoned to loneliness Luise seemed contented enough until 1820, and devoted herself to her two young sons Ernst and Albert.

But then a malicious rumour began circulating at the Saxe-Coburg court that in response to neglect by her increasingly absent husband – Luise had consoled herself with one of Ernst’s own friends…”

The Birth of Prince Albert

In May 2019 we celebrated the bicentenary of Queen Victoria; this month we will mark that of her husband Prince Albert, who was born at Schloss Rosenau in Bavaria on 26 August 1819.

In my last Footnotes article I told the fascinating story of the pioneering German midwife, Charlotte von Siebold, who delivered both babies. But while we know a great deal about Queen Victoria’s parents, their marriage and her birth, the facts of Prince Albert’s early life are often skimmed over in biographies. Books in English often do not have very much to say about Albert’s mother, Princess Luise married his father Duke Ernst I of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld on 3 July 1817. [In 1826 it became Saxe-Coburg-Gotha when the German duchies were rearranged.]

Rosenau Castle, Thuringia, Germany. Birthplace of Prince Albert

Rumours at the Saxe-Coburg Court

Despite being an arranged marriage, it started happily enough: Luise like many royal brides of her generation was married young: engaged on her 16th birthday, married before her 17th and mother of her first son 11 months later. Sweet, friendly and animated, Luise was a typical bubbly 17-year old, impressionable and romantically minded. But she had married a man twice her age, whose major preoccupations in life were hunting, drinking and womanizing. Although at times bewildered by her husband’s selfish behaviour and abandoned to loneliness Luise seemed contented enough until 1820, and devoted herself to her two young sons Ernst and Albert. But then a malicious rumour began circulating at the Saxe-Coburg court that in response to neglect by her increasingly absent husband – Luise had consoled herself with one of Ernst’s own friends, Alexander Graf zu Solms.

Luise vehemently denied the accusations, but Ernst – and this despite his own continuing infidelities – took the rumours seriously and began keeping watch on his wife. Consumed by jealousy, he began plotting with his personal advisor and aide de camp Maximilian von Szymborski for Luise’s removal. Szymborski, it is said, had his own reasons for wishing Luise out of the way: there is little or no evidence to go on, but rumours persist of a homosexual relationship between the two men. However, another suggestion, made in a 1937 article on the heredity of the royal caste, contended that Szymborski himself had been Luise’s lover and the father of her son Albert!

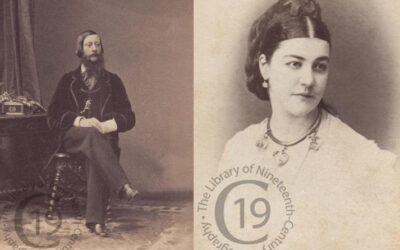

Albert and brother Ernst with mother Duchess Louise of Saxe-Coburg

Luise’s Banishment from Coburg

In September 1824 despite public protests by Coburgers loyal to Duchess Luise, she was prevailed upon by Szymborski to sign a deed of separation, and was sent from Schloss Ehrenburg and settled in St Wendel in the Principality of Lichtenberg. Far worse, Luise was forced to leave her two young sons, Ernst (6) and Albert (5), behind. She never saw them again. In St Wendel Luise entered into a new relationship – with Alexander Von Hanstein, whom she married after her divorce from Ernst in March 1826.

From the moment of her departure from Coburg, Luise was turned into the villain of the piece by her former husband Ernst in order to protect him and the reputation of the Saxe-Coburg-Gotha throne. The allegations against her that followed never offered any balance or sympathy toward her position. They were still current when news was announced at the end of 1839 that Queen Victoria was to marry Luise’s youngest son, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha.

Anti-German gossip in England

During the run up to the marriage of Victoria and Albert, there was considerable scurrilous anti-German gossip directed at Albert, but this was mainly in response to quarrels about his status and his income on the Civil List. But suggestions that the queen’s Consort was illegitimate also surfaced, though these were clearly politically motivated and confined to the radical and satirical press. Little note was taken of them at the time.

Had such rumours been taken seriously this would have alarmed officialdom and might have caused the British government to advise Victoria against marrying Albert. We know nothing of Albert’s response to the rumours, but he was clearly aware of them. Having a horror of all and any sexual scandal, and haunted by his parents’ divorce, he chose to avoid discussion of the subject. Indeed, he always referred to his long absent mother with considerable affection; and his father – for all his obvious sexual proclivities – as a paragon of virtue. Albert always had a blind spot where his father’s weaknesses were concerned, Victoria too.

Pauline Panam’s Kiss and Tell Memoirs

However, Albert must have known of the scandal that had rocked Saxe-Coburg and beyond. In 1823, an actress named Pauline Panam – but better known by the stage name La Belle Grecque – who had been one of his father mistresses and had borne an illegitimate son by him –– published her very damning memoirs in Paris. Ernst tried hard to suppress them but soon the scandal was all over the European courts and salons.

In 1915 a condensed English version of Panam’s memoirs under the very pointed title, A German Prince and His Victim brought attention to her claims in the English-speaking world. In her book she noted that ‘a certain Baron von Meyern, Chamberlain at the Court, a charming and cultivated man, of Jewish extraction’ was ‘supposed to have taken Ernst’s place in the fair Louise’s heart’.

The publication of a German book England als Erzieher by Max W L Foss in 1921 fomented the rumours about illegitimacy, also alleging that Albert was a ‘half-Jew’ – Luise’s bastard son by the same Coburg courtier Ferdinand Freiherr von Meyern, nominated by Panam. That same year, 1921, British writer Lytton Strachey was the first to pick up on the supposed Saxe Coburg ‘scandals’ and Luise’s affair with a courtier of ‘Jewish extraction’, in his Queen Victoria, though without naming names. Further insinuations on this score were made in Laurence Housman’s stage play Victoria Regina in 1934. More recently The Coburg Conspiracy by Richard Sotnick, revived the ‘Jewish father’ rumour, alleging in 2008 that Albert was in fact the son of a fairly lowly ‘Jewish’ footman employed at Schloss Ehrenburg during 1818-19 named Friedrich Blum.

Did Prince Albert Look Jewish?

So: did Albert look Jewish, as has repeatedly been claimed in support of these stories?? The jury is out on that one, some asserting in Albert’s defence that he in fact had the same prominent Coburg nose that occurred in several members of his and the British royal family.

One of the first biographers to defend Duchess Luise from these unproven allegations was Hector Bolitho, in his 1932 biography Albert the Good. In 1950 in his A Biographer’s Notebook, Bolitho once again vigorously rejected the rumours of Albert’s illegitimacy and debunked the claims about zu Solms. In 1958 Doris A Ponsonby, in her biography of Luise The Lost Duchess confirmed Bolitho’s defence of her. Evidence on Sotnick’s candidate Blum, too, has never been sufficiently substantiated and it would seem that he was not in fact Jewish – that is merely family legend.

Luise’s 2nd husband Alexander von Hanstein

The only solid evidence of Luise having any other sexual relationship bar that with Ernst was with her second husband Von Hanstein. David Duff in Albert & Victoria (1972) talks of an affair between them in 1824 – but that was not till five years after Albert’s birth. Hanstein born 1804 would only have been only 14 at the time of Albert’s conception! It is interesting to note the date of this revelation – 1824 – for this is a year after the scandal had broken about Ernst’s affair with Pauline Panam, at a time when she was still garnering a lot of public attention and making things extremely uncomfortable for him. What better tactic than for Ernst’s Mr Fixit, Szymborski, who had so efficiently rid him of Luise, to ruthlessly deflect attention from the duke and onto her?

Maybe Luise did indeed begin an affair with Hanstein at around the alleged time. He had been a lieutenant of the Coburg battalion at the time, and who could blame her, given Ernst’s profligacy and humiliating treatment of her? Luise never confirmed or denied the accusation; adultery with von Hanstein was cited in her divorce papers and she married him in 1826. But there simply is nothing to suggest she was unfaithful to Ernst in 1818. Whatever the rumours, or their veracity, the question remains: if Ernst had been so convinced of his wife’s infidelity at the time of Albert’s birth in 1819, would he not have sent her packing then??

Or Was Prince Leopold the Culprit?

More recently, even more spurious suggestions have been made that Albert was in fact the son of Leopold, King of the Belgians – Duke Ernst’s own brother. According to this theory, Leopold had seduced his forlorn sister-in-law during a visit he made to Coburg in the autumn of 1818, at around the time Albert would have been conceived. Leopold in those days was, after all, celebrated as one of the most handsome men in Europe; he was also, like his brother a notorious roué. Could the vulnerable, 18 year old Luise really have fallen prey to him that autumn – when she herself said she had been ill ‘for a long time’ with chicken-pox! In her letters she talks of spending a lot of her days ‘alone with my ladies’ while the two brothers were out all day hunting – and probably womanizing too.

In his book The Coburg Conspiracy, Richard Sotnick mentioned claims made ‘in German history circles’ about Leopold as Albert’s father but provided no documentary proof, alluding instead to a letter supposedly in the Staatsarchiv Coburg in support of this. In the absence of evidence such claims remain fanciful. They are, of course, good material for TV drama, but, failing any new evidence coming to light, that is where we must leave them – to the reader’s fertile imagination.

Latest Articles and Media about Queen Victoria, Prince Albert & their times

Mad Lord Adolphus, Lady Susan and Bertie’s Baby

Even Queen Victoria, who privately loved tittle-tattle but never admitted to it, could not resist being drawn into the saga of mad Lord Adolphus Vane-Tempest and his poor wife Susan…

The Curious Tale of Queen Victoria’s dresser

From Windsor Castle to North Dakota – a fascinating tale of pioneer spirit and triumph over adversity by English immigrants.

Charlotte von Siebold – the Pioneering German Midwife who delivered Queen Victoria

At the time of the future Queen Victoria’s birth, ‘the excellent Mademoiselle Siebold’ emerged from the delivery room to announce the birth of a girl to the gathered dignitaries with considerable delight, adding in her thick German accent: ‘Verr nice beebee. No big but full. You know, leetle bone, mush fat.’

Queen Victoria: Pet Names, Titles, Nicknames & Aliases

During her 63 year reign Queen Victoria acquired a wealth of these. Many were complimentary and affectionate, some were ironic or satirical, and others were downright rude…

The Victorian Christmas

The cosy Dickensian Christmas referred to in Queen Victoria’s diary for Christmas Eve 1860, was in great part popularized by Victoria and Albert after their marriage in 1840. During the 21 years that followed they did much to set their own particular stamp on how the festival is celebrated in this country.

Back Home in Dickensland

As children we were fearless. Mean, and muddy, and at times dispiriting it may have been, but the Medway Estuary was our paradise. My own daydreams draw me there still…

Sarah Forbes Bonetta: the Captive African Princess Gifted to Queen Victoria

In its Christmas Special for December 2017 the ITV series Victoria featured the story of Sarah Forbes Bonetta, a captive African princess who was brought to the court of Queen Victoria. She has frequently been described as the Queen’s goddaughter’ but this is not in fact true…

Queen Victoria’s dress sense – or lack of it

Queen Victoria’s dress sense – or rather, lack of it – was a subject that regularly provoked the despair of her courtiers. Despite his best efforts, the court painter, Franz Winterhalter, who painted some of the most fashionable women in Europe, could not disguise Victoria’s slightly provincial air…

Queen Victoria’s Passion for Photography

The 63-year reign of Queen Victoria brought with it much invention and innovation, but nothing has probably been more significant in defining the mental picture we all of have of her and Victorian everyday life than the photograph.