Sarah Forbes Bonetta: the Captive African Princess Gifted to Queen Victoria

“Queen Victoria always had a fascination for her black and colonial subjects at a time when such interest was rare among the white aristocracy. She readily took up the cause of a ‘Dahoman captive’, affectionately calling her Sally, and becoming a loyal friend and protector until she was old enough to marry..”

The Real Story of Sarah Forbes Bonetta

In its Christmas Special for December 2017 the ITV series Victoria featured the story of Sarah Forbes Bonetta, a captive African princess who was brought to the court of Queen Victoria. She has frequently been described as the ‘Queen’s god daughter’ but this is not in fact true; nor, as has been suggested, did the queen ever bring her to live with the royal family at Windsor or any other royal residence. Here is the true story, but more is still being uncovered:

In 1850 Queen Victoria took to her heart and sponsored a chieftain’s daughter from the Egbado tribe, who had been saved from being sacrificed by a rival tribe in the West African kingdom of Dahomey. Her rescuer was a British naval officer, Commander Frederick Forbes, who had been sent as British envoy to King Guezo of the West African kingdom of Dahomey, during a bout of British gunboat diplomacy designed to induce the king to abandon the slave trade, something that Guezo was reluctant to do, for slavery accounted for his principal revenue. Guezo, said to have 18,000 wives as well as a personal bodyguard of 8,000 Amazons – who were also used in hunting for slaves – was notorious for his penchant for ceremonial human sacrifice, which he often laid on for visiting foreigners. Many of these victims were slaves or captives from the higher born of the rival tribes, chosen for their nobility or royal tribal lineage.

On visiting King Guezo, Forbes somehow managed to persuade the king to spare the 7-year-old girl who was about to be sacrificed for his entertainment, and make a gift of her to Queen Victoria instead – as a present ‘from a Black King to a White Queen’. He brought her back to England, on his boat the HMS Bonetta, giving her the name Sarah Forbes Bonetta (her real African name is thought to have been Aina.)

The little ‘Dahoman Captive’

Sarah’s education in Africa

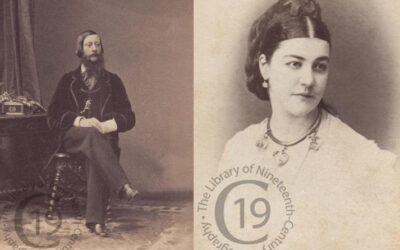

Marriage to James Davies

Victoria Davies, Queen Victoria’s Black god-daughter

Sarah named her first child, a daughter, after the Queen, who agreed to be the child’s godmother and presented baby Victoria with a gold cup, salver, knife, fork and spoon – all in gold, the cup and salver inscribed ‘To Victoria Davies, from her godmother, Victoria, Queen of Great Britain and Ireland, 1863’. She had two other children: Arthur (1871) and Stella (1873). In December 1867 during a visit to England, Sarah had seen the queen for the last time, at Windsor. Victoria again recorded the event in her journal: ‘saw Sally, now Mrs. Davies & her dear little child, far blacker than herself, called Victoria & aged 4, a lively intelligent child, with big melancholy eyes’. Sarah was, however, now sick with tuberculosis and went to Madeira for her health, where she died in 1880 at the age of about 37. The queen heard the news on the very day she was expecting a visit from her godchild Victoria, to whom she offered her maternal comfort, later resolving in her journal ‘I shall give her an annuity’. Queen Victoria held true to her word as godmother to Victoria Davies, and paid for her education at Cheltenham Ladies College during 1881–3. Victoria remained in touch with the queen for many years after her marriage. She had two children, Jack and Beatrice and their descendants still live in Lagos today.

Latest Articles and Media about Queen Victoria, Prince Albert & their times

Mad Lord Adolphus, Lady Susan and Bertie’s Baby

Even Queen Victoria, who privately loved tittle-tattle but never admitted to it, could not resist being drawn into the saga of mad Lord Adolphus Vane-Tempest and his poor wife Susan…

The Curious Tale of Queen Victoria’s dresser

From Windsor Castle to North Dakota – a fascinating tale of pioneer spirit and triumph over adversity by English immigrants.

Prince Albert’s Birth: Is there any truth in the rumours of illegitimacy?

Books in English often do not have very much to say about Albert’s mother, Princess Luise of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg. Did her husband’s womanising push her into the arms of another man?

Charlotte von Siebold – the Pioneering German Midwife who delivered Queen Victoria

At the time of the future Queen Victoria’s birth, ‘the excellent Mademoiselle Siebold’ emerged from the delivery room to announce the birth of a girl to the gathered dignitaries with considerable delight, adding in her thick German accent: ‘Verr nice beebee. No big but full. You know, leetle bone, mush fat.’

Queen Victoria: Pet Names, Titles, Nicknames & Aliases

During her 63 year reign Queen Victoria acquired a wealth of these. Many were complimentary and affectionate, some were ironic or satirical, and others were downright rude…

The Victorian Christmas

The cosy Dickensian Christmas referred to in Queen Victoria’s diary for Christmas Eve 1860, was in great part popularized by Victoria and Albert after their marriage in 1840. During the 21 years that followed they did much to set their own particular stamp on how the festival is celebrated in this country.

Back Home in Dickensland

As children we were fearless. Mean, and muddy, and at times dispiriting it may have been, but the Medway Estuary was our paradise. My own daydreams draw me there still…

Queen Victoria’s dress sense – or lack of it

Queen Victoria’s dress sense – or rather, lack of it – was a subject that regularly provoked the despair of her courtiers. Despite his best efforts, the court painter, Franz Winterhalter, who painted some of the most fashionable women in Europe, could not disguise Victoria’s slightly provincial air…

Queen Victoria’s Passion for Photography

The 63-year reign of Queen Victoria brought with it much invention and innovation, but nothing has probably been more significant in defining the mental picture we all of have of her and Victorian everyday life than the photograph.