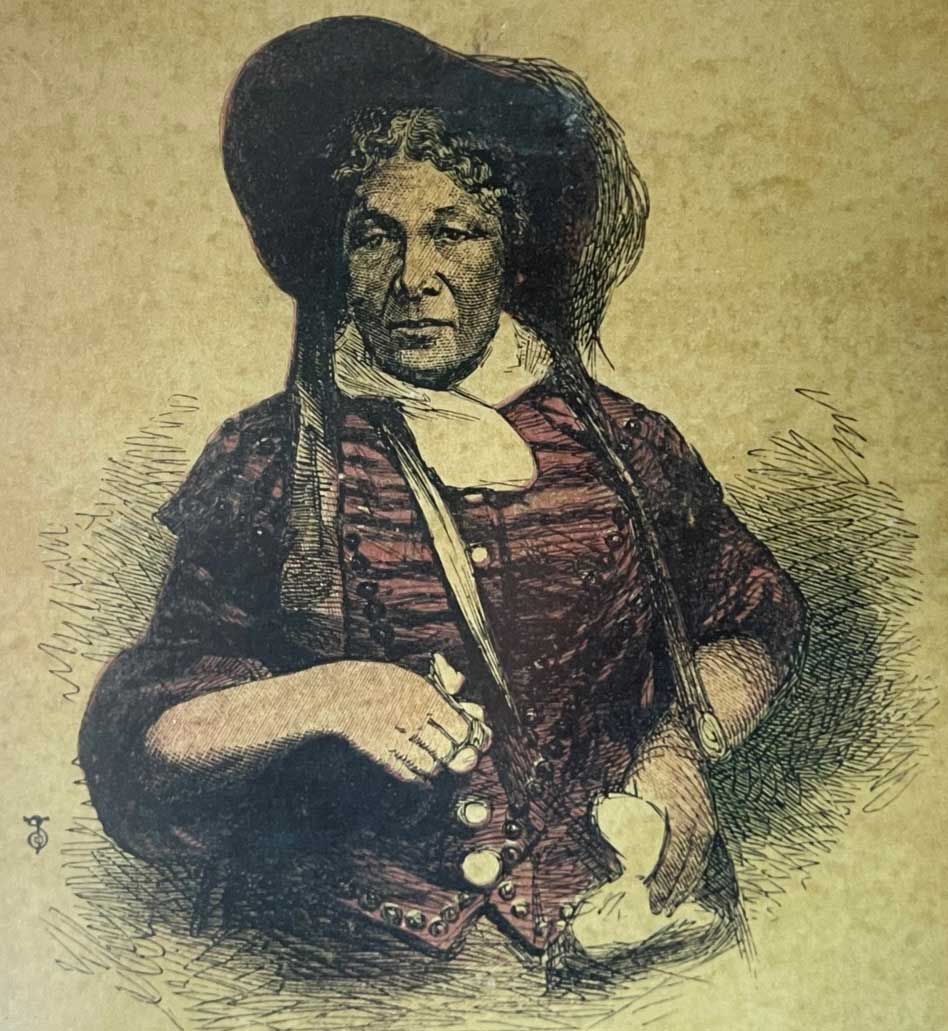

Mary Seacole: Creole Doctress, Nurse & Healer

“In Crimea during 1854–5 Mary Seacole demonstrated that her home-grown Jamaican practice of hygiene, healthy food, natural remedies and kindness – had a lot more to offer than traditional medicine, making her nursing practice a far more modern, holistic one that people might have imagined.”

The Creole Doctresses of Jamaica

Female doctoring skills were well respected in Jamaica and they often seemed to work better in fighting enteric disease than any of the then standard methods. For example, a noted Creole doctress and former slave named Cuba Cornwallis had nursed many sick British sailors in Port Royal in the late 18th century, including a young Horatio Nelson, whom she nursed back to health in 1780 after an attack of dysentery.

Herbal Medicine vs Traditional Allopathic Treatment

These doctresses based their treatments on decoctions of essential barks, roots and fruits that were indigenous in Jamaica. What patient would not have preferred these treatments to being cupped and bled and purged and subjected to strong emetics and sweating, or fed copious amounts of mercury, opium, arsenic and antimony? Such became Mary Seacole’s fame in Crimea that sick men went to her daily ‘surgery’ for advice and a dose of her herbal medicine in preference to reporting themselves sick at the death traps that were their own hospitals in Crimea. It is well known that the vast British hospital at Scutari on the Turkish mainland, to where many of the Crimean wounded were evacuated, had a catastrophic death rate from cross infection and sepsis, despite the best efforts of its superintendent Florence Nightingale.

Mary Seacole did not give us very much detail about her own remedies in her autobiography The Wonderful Adventures of Mary Seacole in Many Lands. But she was categorical about certain things, the first being that ‘the simplest remedies were perhaps the best.’ She soundly rejected all use of opium which she ‘rather dreaded’, alleging that ‘its effect is to incapacitate the system from making any exertion, and it lulls the patient into a sleep which is often the sleep of death’. Instead, she favoured kindness, care and a lot of common sense: the use of gentler medications such as ‘mustard emetics, warm fomentations, mustard plasters on the stomach and the back, and calomel’.

19 July 1855 MORNING ADVERTISER ‘A native of Jamaica she has travelled extensively on the American continent, and has acquired great experience in the treatment of cases of cholera and diarrhoea. Her powders for the latter epidemic are now so renowned that she is constantly beset with applications, and it must be stated, to her honour, that she makes no charge for her powders.’

24 August 1855 DIARY WILLIAM MENZIES CALDER, assistant staff surgeon 49th regiment ‘Her fame as a doctress for cholera and diarrhoea are spread all over the camp. Her powders for diarrhoea and cholera seem to have worked miracles, she used them with great benefit in Panama. They certainly cannot be less efficacious than all our drugs etc. for cholera, from all the varieties of which I have yet seen little benefit here.’

13 March 1856 Gen. Sir Richard Denis Kelly, in AN OFFICER’S LETTERS TO HIS WIFE DURING THE CRIMEAN WAR ‘Among the rest was a black lady from Jamaica, Mrs. Seacoal, who for some time past has established a restaurant near Kadikoi. She was also principal medical officer to the army works corps or ci-devant navvies, and at the time of the cholera last summer used to prescribe pomegranate juice, which was an almost never-failing specific.’

31 January 1857 ‘REMINISCENCES OF THE WAR IN THE EAST BY A MILITARY CHAPLAIN’ ‘She held a levee every morning after breakfast, when you were sure to meet with sick men of every nation, belonging to the Land Transport, whose camp was near at hand waiting for a preventive against cholera, fever or the other incidental illnesses of the place.’

11 April 1857 THE TIMES Her hut was surrounded every morning by the rough navvies and Land Transport men, who had faith in her proficiency in the healing art, which she justified by many cures and by removing obstinate cases of diarrhoea, and similar camp maladies.’

So what exactly were these ingredients in Mary’s 1850s medicine chest?

Sugar of lead: Sugar of lead is another name for lead acetate. This was normally applied externally. Taken internally (Mary added 10 grains to a pint of water giving one patient a table spoonful every quarter of an hour) it was a purgative but could have toxic effects if the dosage was exceeded.

Mercury: Mary says that she applied mercury externally. It was formerly employed in this way in the treatment of syphilis and chronic skin diseases – neither of which seem to have been used by Mary in this way when she was in Panama or Crimea. Although some mercuric oxides have antibacterial properties we don’t know what kind of mercury Mary used.

Calomel: Calomel is another name for mercurous chloride. Depending on dosage, it has the same toxicity as mercury. It was used primarily as a purgative by British army surgeons in Crimea and was also a treatment for syphilis, psoriasis and eczema.

By far the most significant ingredient in Mary Seacole’s pharmacopaeia was Pomegranate: its rind and juice contains an astringent which is still commonly used against diarrhea and dysentery in many parts of the world today. There is good evidence that it works as a reasonable treatment though no medical tests have been done. Pomegranate bark, if ground to a paste, was also sometimes used for the expulsion of tapeworms and as a purgative. While Mary might have had difficulty obtaining some of her regular Jamaican ingredients in Crimea, there would have been no problem obtaining pomegranates which grew in profusion all around the Black Sea.

Pomegranate rind, logwood and mahogany and other remedies based on tree bark all featured strongly in Thomas Dancer’s The Medical Assistant or Jamaica Practice of Physic, published in 1801, and which Mary is sure to have consulted. She liked to sweeten her sometimes bitter-tasting decoctions with guava jelly to make them more palatable. Dancer’s book had been written specifically ‘for the use of families and plantations’ for the treatment of African slaves falling victim to a range of enteric disease in the very different, humid climate of Jamaica.

In Crimea during 1854–5 Mary Seacole demonstrated that her home-grown Jamaican practice of hygiene, healthy food, natural remedies and kindness – had a lot more to offer than traditional medicine, making her nursing practice a far more modern, holistic one that people might have imagined. Back in England after the war, she later offered her own remedies free during a Cholera epidemic in London.

Here is a short feature that I did with black historian David Olugosa for BBC 1’s The One Show in which we discussed Mary’s herbal remedies

You may also like

George Bridgetower: The Black Violinist at the Court of the Prince of Wales

The Extraordinary life of George Augustus Polgreen Bridgetower, the violin prodigy who stunned Europe in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, like so much of black history from the Victorian era and before, is even now only infrequently mentioned.

Sarah Forbes Bonetta: the Captive African Princess Gifted to Queen Victoria

In its Christmas Special for December 2017 the ITV series Victoria featured the story of Sarah Forbes Bonetta, a captive African princess who was brought to the court of Queen Victoria. She has frequently been described as the Queen’s goddaughter’ but this is not in fact true…