George Bridgetower

The Black Violinist at the Court of the Prince of Wales

Haydn, it is said, had given young George violin lessons and was the first to take note of his prodigious musical gifts.

The Extraordinary life of George Augustus Polgreen Bridgetower, the violin prodigy who stunned Europe in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, like so much of black history from the Victorian era and before, is even now only infrequently mentioned. He appears mainly in brief and often inaccurate, web and published sources; even historians of music have overlooked Bridgetower’s extraordinary contribution to the British performing arts. For a long time fragments of his story were only to be found in specialist books about blacks in eighteenth-century British society; in scholarly tomes on Beethoven and Haydn; or reference works, such as the Grove Dictionary of Music.

I have been nursing George Bridgetower’s story for almost as long as that of Mary Seacole and hope to write up my research on him before too long, for he is an equally intriguing figure. However, as with Mary Seacole’s story, there are many gaps, puzzles and dead ends. But let’s begin with his astonishing debut:

Paris, April 1789

Just three months before the outbreak of the French Revolution, a ten-year-old boy ventures out on to the stage of the Salle des Cent Suisses in the Tuileries Palace to perform for the Concert Spirituel – Paris’s pre-eminent concert-giving society – and demonstrates his prodigious gifts as a violinist to the glittering assembly. But this boy is different. For he is not white, but of mixed race: his father is a former West Indian slave who is a court attendant to Prince Hieronimus Wincenty Radziwill; his mother is of German-Polish descent. The following day, the performance of this ‘jeune nègre des colonies’, George Bridgetower, is the talk of Paris; a later concert on 27 May was attended by American statesman Thomas Jefferson and his daughter Patsy. By the summer young George is the toast of English society, which delights in the novelty of the boy’s exotic appearances wearing ‘the fancy dress of a Polish black’. But it is not just the young George who attracts attention over the following months at the most select concert halls of Bath, Bristol and London – it is the equally fascinating if not awe-inspiring figure of his showman father, who accompanies him, dressed à la Othello, in a turban and Turkish-style robes.

At the Court of Prince Esterhazy

The name Bridgetower is an extraordinarily rare one, known only in Barbados. It is probably a corruption of the name Bridgetown, the capital city of the Island. George Augustus Polgreen Bridgetower was, however, born in Biała, in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, (now eastern Poland) on 13 August 1778. His father, John Frederick August Bridgetower, a former slave and an adventurer with a gift for self-promotion, was almost certainly Barbadian; his mother, Maria Ursula Schmid, a German-Polish woman, whose identity is not yet fully known, but who was probably a servant of the Radziwill family.

Shortly after George’s birth his father took his family to Austria where he took employment with Prince Esterhazy and his family at their summer residence, the Castle Esterhazy at Eisenstadt, 30 miles south of Vienna. The Esterhazys were the most wealthy and influential aristocrats in the 18th-century Austrian empire, and had a reputation for their lavish patronage of music and the arts.

Having renovated Castle Esterhazy in ornate style as a ‘Hungarian Versailles’, Prince Miklos Jozsef Esterhazy assembled his own private orchestra there, appointing as its Kapellmeister Joseph Haydn. Haydn, it is said, had given young George violin lessons and was the first to notice his prodigious musical gifts. Whether he did or not, in 1786 John Bridgetower left the Esterhazy estate and took seven-year-old George to make his musical debut in Frankfurt. From there the family spent time in Mainz, with George performing in Brussels, the Hague and elsewhere in Europe, before travelling to England in 1789 for a series of concerts.

‘Little Bridgetower the African’

Haydn joined the Bridgetowers there in 1790, conducting a series of concerts at which the young George took centre stage as a soloist. The boy was much talked about in the papers as the ‘son of an African Lord’ and of a ‘Polish Dutchess’, with concert programmes also making much of his father John’s claims to celebrity and black royalty. This grand, imposing man, in his blue silks and turban, his silver and diamonds, went under an assortment of sobriquets, as ‘August the Moor’, ‘the African Prince’ and even the ‘Abyssinian Prince’, and mysteriously claimed direct descent from the throne of Abyssinia itself. He was fascinating and cultured – a polyglot – fluent in French, German, Italian and Polish – a ‘Black o’Moor of infinite talents’, as Dr Johnson’s friend Hesther Thrale, observed. Others were less impressed by his overweening manner and ingratiating behaviour and his habit of accosting his son’s patrons and admirers for loans of money. Despite being handed copious piles of gold guineas taken at his son’s concerts, John Bridgetower spent the money fast. There was talk of his profligacy, his gambling and his womanising. In the eyes of many he was an impostor, if not a scoundrel.

The appearance of a black virtuoso violinist was not in itself something new in Georgian London. Another famous performer, the 50-year-old Gaudeloupian, Chevalier de Saint-Georges had preceeded Bridgetower in 1787. Any prodigious new talent on the violin would have provoked curiosity – but the fact that George Bridgetower was only twelve and of mixed race guaranteed he would be taken note of in a society where black people featured only as exotic servants. The unanimous praise for young Bridgetower’s gifts prompted a reappraisal of received attitudes to race, for here was a gifted young black who clearly demonstrated that he was an artistic force to be reckoned with. As the Mercure de France noted:

“His talent, as genuine as it is precocious, provides one of the best answers that one can make to the philosophers who would deny to those of his nation and of his colour the faculty of distinguishing themselves in the arts.”

Having performed first in Bath and Bristol to considerable acclaim, young George proceeded on a whirlwind itinerary, with concerts in London at the highly fashionable assembly rooms in Hanover Square, the Theatre Royal Drury Lane, the Italian Opera at the King’s Theatre Pantheon, the Theatre Royal Covent Garden, as well as a variety of charity performances and benefit concerts. The most notable of his performances, in the view of many, was that of a violin concerto by the Italian virtuoso Giovanni Battista Viotti, in which he ‘played to perfection, with a clear, good tone, spirit, pathos, and good taste’.

However, worrying stories soon surfaced about John Bridgetower’s treatment of his young son. At Windsor, where he had played in a private concert at the Lodge, George had confided in Charlotte Papendiek, mistress of the Queen’s Wardrobe, that his father treated him with ‘brutal severity’ and that he had ‘left his mother in distress’. Even the money George earned from his performances was, according to the boy, wasted by his father ‘in crime’. With the help of Papendiek, young George took refuge at the Prince of Wales’s residence, Carlton House. The prince, a great patron of music and himself a cellist, immediately summoned John Bridgetower to Carlton House; he ordered him to leave the country, providing him with the money for his journey and intending to take responsibility for George as his personal protégé.

At the Court of the Prince of Wales

Divested of the outlandish garments that had made him a constant object of curiosity George was now ‘clad in the English fashion of the day’. The Europeanization of the ‘African-Polish’ boy from Eisenstadt had begun.

Having been impressed with Bridgetower’s musical gifts, the Prince of Wales now took it upon himself to recommend the young violinist as ‘an acceptable novelty to the Admirers and Lovers of Music’. He not only paid for George’s tuition in violin by the celebrated French violinist François Barthélemon (a close friend of Haydn), and in composition by the composer and organist Thomas Attwood, but he also financed trips abroad for tuition and encouraged him to learn by listening to the performances of all the violin stars of the day – Giardini, Cramer, Salomon and Viotti – who appeared at the prince’s private concerts at Carlton House. Under the prince’s patronage, and now (in 1795) appointed First Violin in his private orchestra, based at the Brighton Pavilion – a post he would hold for 14 years – Bridgetower steadily moved up the ladder of London’s musical hierarchy. In 1807 he became a fellow of the Royal Society of Musicians and in 1811 took his Bachelor of Music degree at Cambridge. For a while, it is clear that young George lived at Clarence House with the prince and his wife, Princess Caroline, until she was forcibly ejected by her disgruntled husband in 1797. During my research I came across a suggestion that perhaps young George had become too friendly with the princess, for he certainly remained in touch with her.

In 1802 George was given leave of absence to visit his mother who was now living in Dresden, where she and Bridgetower senior had settled with their younger son Frederick. John Frederick appears to have disappeared from view in around 1799; there is no record of his death but evidence suggests he may have returned to England to try his con-artist’s luck again.

Beethoven’s ‘Sonata Mulattica’

From Dresden George travelled to Vienna in 1803, for violin tuition and performances, having been given letters of introduction to elite aristocratic circles there. Here he met the distinguished musical patron Prince Lichnowsky, who in turn introduced him to his close friend, Beethoven. The composer immediately took to the young violinist. He was, at the time, drafting one of his finest works, the Violin Sonata No. 9 in A Major – now famously known as the Kreutzer Sonata. So impressed was he with Bridgetower that he invited him to play the sonata at its premiere at the Augarten Concert Hall in Vienna on 24 May 1803.

It was a nerve-wracking but also exhilarating experience for the 25-year-old George. Beethoven had still been furiously writing the piece hours before the concert, so that Bridgetower had to sight-read some passages from the manuscript, with Beethoven simultaneously improvising on the piano. The premiere was a musical sensation, attended by a glittering crowd of European aristocrats, with Beethoven leaping up from the piano barely half-way through the first movement to embrace Bridgetower when he improvised an arpeggio mid-flow. The audience demanded two encores. This performance was featured in the 1994 film Immortal Beloved starring Gary Oldman as Beethoven, with George Bridgetower played by black violinist Everton Nelson.

At the celebrations held after the performance, the composer grandly declared that he would dedicate the work to Bridgetower, writing across his copy the inscription: “Sonata Mulattica Composta per il Mulatto Brischdauer – gran pazzo e compositore mulattico”, a dedication using the German form of Bridgetower’s name and which by defining him as ‘gran pazzo’ – great madman – underlined George’s reputation for being moody, troubled and temperamental.

However, within hours of him writing this dedication, Beethoven flew into one of his legendary rages, and scratched out the dedication to Bridgetower, the reason apparently being that the violinist had made an ill-judged, salacious remark about a woman whom the composer admired. The sonata was offered instead to the virtuoso violinist Rudolphe Kreutzer in Paris, who, when he received the manuscript took one look at it and declared it ‘outrageously unintelligible’. He never ever performed it; it was given his name but it should, by rights, be called the ‘Bridgetower Sonata’.

Portrait of George Augustus Polgreen Bridgetower, by Henry Eldrdge

The Lost Years

In the following years, Bridgetower returned to England where he taught violin and piano and continued to perform regularly in concerts in London. But after his appearances at the first season of the Royal Philharmonic Society in 1813, and now in his late thirties, he rapidly disappeared from view.

In 1816 he had married well, at the society church, St George’s Hanover Square. His wife was Mary Leach Leake, of Hampstead, daughter of a wealthy cotton manufacturer. By 1819, and with a daughter named Felicia (a previous daughter Julia appears to have died), the couple left England for the Continent, spending time in Rome and in Paris, where Bridgetower became friends with the young composer Saint-Saëns and mixed with many musicians and composers of the day. There were occasional return visits to England, but digging out the details of Bridgetower’s later life and the fate of his wife and child, his parents and brother has all proved challenging. George and Mary were legally separated by 1828. She stayed on in Rome, where she died in 1835.

Bridgetower himself seems to have lived in Rome for a while, and spent many years as a jobbing violinist/teacher working and touring in Europe and regularly returning to London, but as such his early musical celebrity had passed and by the mid 1820s he appears to have been displaced by the new celebrity violinist Paganini. He lived with his daughter Felicia for a while, but seems to have suffered mental problems and bouts of depression; a later legal battle with Felicia and his grandsons suggests a profound breach in their relationship. Perhaps this, and the breakdown of his marriage, accounts for Beethoven’s description of Bridgetower; perhaps he was bi-polar? Either way he swiftly disappeared into obscurity; as early as 1858 the Musical World sadly reported that ‘the name “Bridgetower” is found in none of our musical lexica, nor have we any means in our ordinary sources of information at arriving at his biography.’

A dedicated Beethoven admirer, poet and violinist, John Wade Thirwall, was one of the last to see Bridgetower. He had had sought him out in 1860, and was shocked to find Bridgetower, sick and lonely and living in squalid lodgings in Peckham, south London. During their conversation Bridgetower reminisced about his friendship with Beethoven and ruefully conceded how his flippant remark had denied him enduring musical celebrity and a posthumous reputation: ‘If only I hadn’t made that remark,’ he told Thirwall, ‘my name would have lived on into the future.’

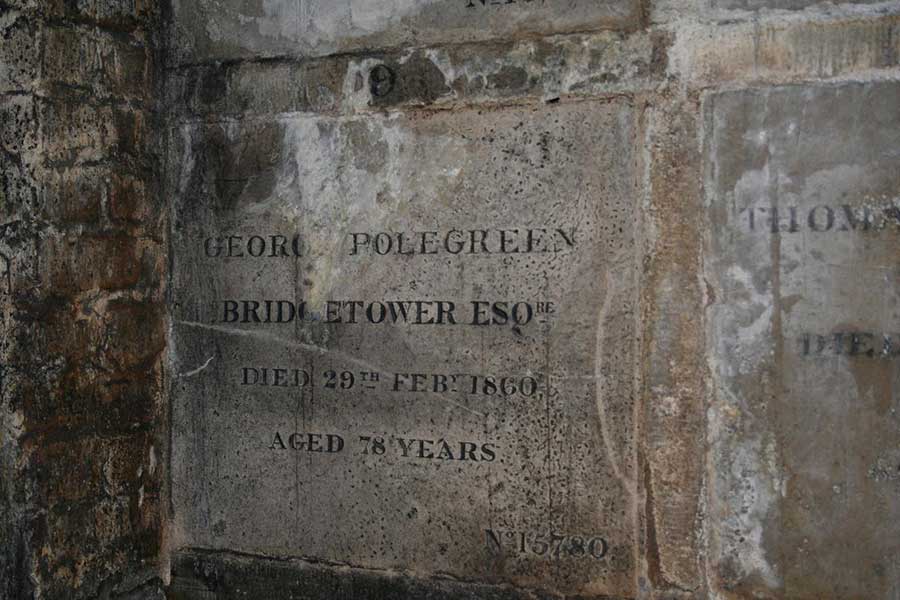

On 29 March 1860 George Bridgetower died alone and forgotten at No 8 Victory Cottages, Montpelier Road, Peckham – a house long since demolished. He left behind several compositions, most of them now lost, but a few manuscripts survive in the British Library: the Diatonica Armonica, Henry, A Ballad, dedicated to the Princess of Wales, and ‘Jubilee: Rule Britannia & God Save the King, a quintet with variations. He is buried in the catacombs at Kensal Green Cemetery. I sought out his simple resting place there a few years ago. The age is wrong; he was 82.

George Bridgetower’s stunning London debut in 1790 had overturned many preconceptions about the intellectual and artistic abilities of black people. It demonstrated that they could display equally prodigious artistic talents as white musicians. In comparison, the black violinist and composer Joseph Antonio Emidy (1775?-1835) had fared far less well. Captured into slavery from the Guinea Coast by Portuguese slavers, and later press-ganged into the British navy, he had settled in Cornwall, where for the next 30 years he had composed a considerable musical opus – all of which has since been lost to us.

Curiously, although a contemporary of Bridgetower, Emidy appears not to have provoked the same interest. For although his music was shown to the impresario Johann Salomon, who had promoted Bridgetower’s concerts with Joseph Haydn, he was never brought to London to perform. The reason for Emidy’s rejection had been made clear: ‘his colour would be so much against him, that there would be a great risk of failure’.

It would seem, therefore that the handsome young mixed-race Bridgetower – as the two surviving images of him attest – had projected an acceptable cultured, Europeanized ‘blackness’. Thanks to his carefully orchestrated promotion by his gifted showman of a father, George had been well received in polite society, playing as he did works strictly from the white, European repertoire. It is clear too that the patronage of the Prince of Wales, later George IV, as well as Joseph Haydn and other prominent society and musical figures, had played a crucial role in fostering Bridgetower’s exceptional rise through British musical society.

There is much to still discover about the missing chapters in George Bridgetower’s life and I am still searching. What happened to him during those long missing years spent mainly on the Continent 1819-60? So far we have only a fragmentary record. There is too, the tantalizing missing story of his two Italian grandsons by his daughter Felicia. Not to mention the subsequent family claim made to the throne of the Kingdom of Abyssinia! …. But that is another story ….