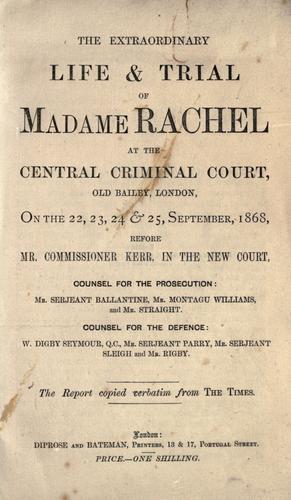

Beautiful For Ever: The True Story of Madame Rachel of Bond Street

“Madame Rachel promised her clients that she would make them ‘Beautiful For Ever!’ But what they found inside her beguiling oriental boudoir with its latticed screens, lavish oriental wall hangings, splashing fountain and heavy crimson drapes, was something far darker. For beneath the clever sales patter and the wheedling manner lay a merciless con-artist and fraudster who made a career out of lies, treachery, and the false hopes of her victims.”

Madame Rachel: purveyor of cosmetics, lies & false hopes

Open any glossy women’s magazine today and its pages are full of the miraculous effects of a whole range of cosmetics and beauty treatments – from high-tech creams, to Botox, hormone injections, fillers and plastic surgery – all designed, at a price, to keep the ageing process at bay.

Back in the 1860s there was little or no choice for women who wanted to look good – that is if they dared meddle with nature at all. In Victorian England the pursuit of beauty was totally frowned upon. Queen Victoria was appalled at its growing popularity: to her mind and that of all respectable women, cosmetics were vulgar and highly improper – resorted to only by actresses and prostitutes. Such was the general hostility to the use of makeup that many women concocted their own cosmetics and creams at home and those who did buy cosmetics and hair colourants did so under the counter, away from public scrutiny.

Only well-heeled society ladies with plenty of money could afford the exclusivity of one of the discreet ‘lady renovators’ or ‘rejuvenators’ then operating in Mayfair. And the person they all flocked to in secret – heavily veiled and by closed carriage – was Madame Rachel of 47a New Bond Street. A self-appointed, but entirely bogus ‘Purveyor of Cosmetics to Her Majesty the Queen’, Madame Rachel promised her clients that she would make them ‘Beautiful For Ever!’ But what they found inside her beguiling oriental boudoir with its latticed screens, lavish oriental wall hangings, splashing fountain and heavy crimson drapes, was something far darker. For beneath the clever sales patter and the wheedling manner lay a merciless con-artist and fraudster who made a career out of lies, treachery, and the false hopes of her victims.

‘Beautiful For Ever!’

Enamelling ladies’ faces