The Pioneer American Newspaper Girls Who Inspired a Novel

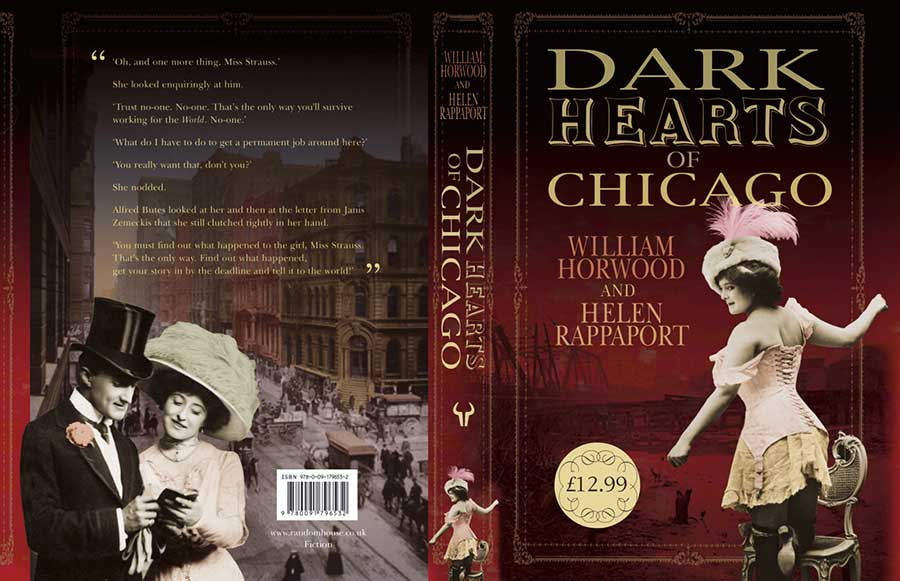

The story behind writing Dark Heart of Chicago

“In the late nineteenth century an extraordinary breed of new journalists appeared on the scene in America. The world had seen nothing like them before. They were young, feisty, courageous and iconoclastic — and they were women.”

Women Journalists appear on the scene

Nellie Bly

It took all Bly’s considerable persuasive skills to talk her way into a job on the World. But within months she had become a household name with a sensational series of reports – ‘Ten Days in a Mad-House’ in which she graphically described to horrified readers of the World her feigning of mental illness in order to engineer her incarceration in New York’s notorious Blackwell Island insane asylum.

The stories filed after her release by Nellie, aka the ‘Pretty Crazy Girl’, were the talk of New York. At a time when women were still generally viewed as demure and virtuous domestic angels, petite, pretty, non-nonsense Nellie Bly was hitting the front pages right across America. She started as she meant to go on, adhering in her news reporting always to her own special mantra:

Determine Right. Decide Fast. Apply energy. Act with Conviction. Fight to the Finish. Accept the Consequences. Move on.

Bly soon capped this story in 1889–90 with one of the biggest and most glamorous publicity stunts of all time, beating Phileas Fogg’s fictional voyage around the world in 80 days by doing the journey in only 72.

Nellie Bly

She made light of her achievement, dismissing it as ‘not so very much for a woman to do who has the pluck, energy and independence which characterize many women in this day of push and get-there’. Needless to say, Bly’s intrepid reporting quickly prompted many other eager but less talented would-be female journalists to mimic her exploits, often risking their lives in order to churn out eye-grabbing headlines such as ‘A Mother’s Awful Crime; ‘A Bride but not a Wife’, ‘Baptized in Blood’. In the all-out war to win precious scoops over each other, the new breed of stunt girls regularly put their lives at risk. Such was the fierce competition between them that one cynical observer alleged that they would even ‘sell their honour for a column of newspaper matter’. With no formal training for journalists then available, these young and naïve cub reporters learnt their craft the hard way, in the university of life. ‘I picked up the facts of life at the police court, the waterfront, the morgue, and the emergency hospital. It was easy for a quick kid,’ recalls a laconic Milly Bennett, who had been only twenty when she started out on the San Francisco Daily News.

In pursuit of a story the Stunt Girls went undercover as sweatshop girls, rag-pickers and box factory workers; they worked as laundresses and flower sellers; posed as chorus girls, serving maids, artist’s models, beggars, lunatics, Salvation Army girls and prostitutes. They went up in balloons, risked attacks of the bends by going down into the caissons of the newly constructed Brooklyn Bridge, rode on elephants and even went into the lion’s cage at the circus. They ventured alone on horseback out into the backwoods to report on mountain feuds and moonshiners and even camped out in haunted houses watching for ghosts. Some subjected themselves to mesmerists. Others risked physical injury by seeking ‘treatment’ at the rough hands of back street abortionists in an attempt to expose their rackets.

Women Journalists: These Women Were A Very Tough Breed

One green young girl reporter, on arriving for her first day on a Utah newspaper, was sent to report on an execution, the paper’s male reporter being too dead drunk to handle the story. Ada Patterson stood on the gallows with the other reporters and watched Arthur Duestrow hang in 1897; in 1899 she witnessed the first electrocution of a woman – Martha Place at Sing Sing in New York. These young women were a very tough breed.

Over on the San Francisco Examiner meanwhile, Annie Laurie (aka Winifred Sweet Black) rapidly established herself as William Randolph Hearst’s answer to Nellie Bly. Feigning sickness on a San Francisco street, Black had had herself carted off to the local public hospital in order to expose the appalling conditions and maltreatment of the poor there. Later, she went undercover in Utah to report on polygamy among the Mormons, but her biggest coup came when she disguised herself as a boy to investigate conditions in the closed city of Galveston, Texas after a freak hurricane in 1900 had killed 7,000 people there. The presses soon rolled, bannering the portentous biblical tones of Black’s leader story: ‘Corpse-Laden Waters Lit by Funeral Pyres: Winifred Black Crosses the Dismal Bay of Death to the Desolate City of Disaster’ – headlines guaranteed to sell thousands of extra copies for Mr Hearst.

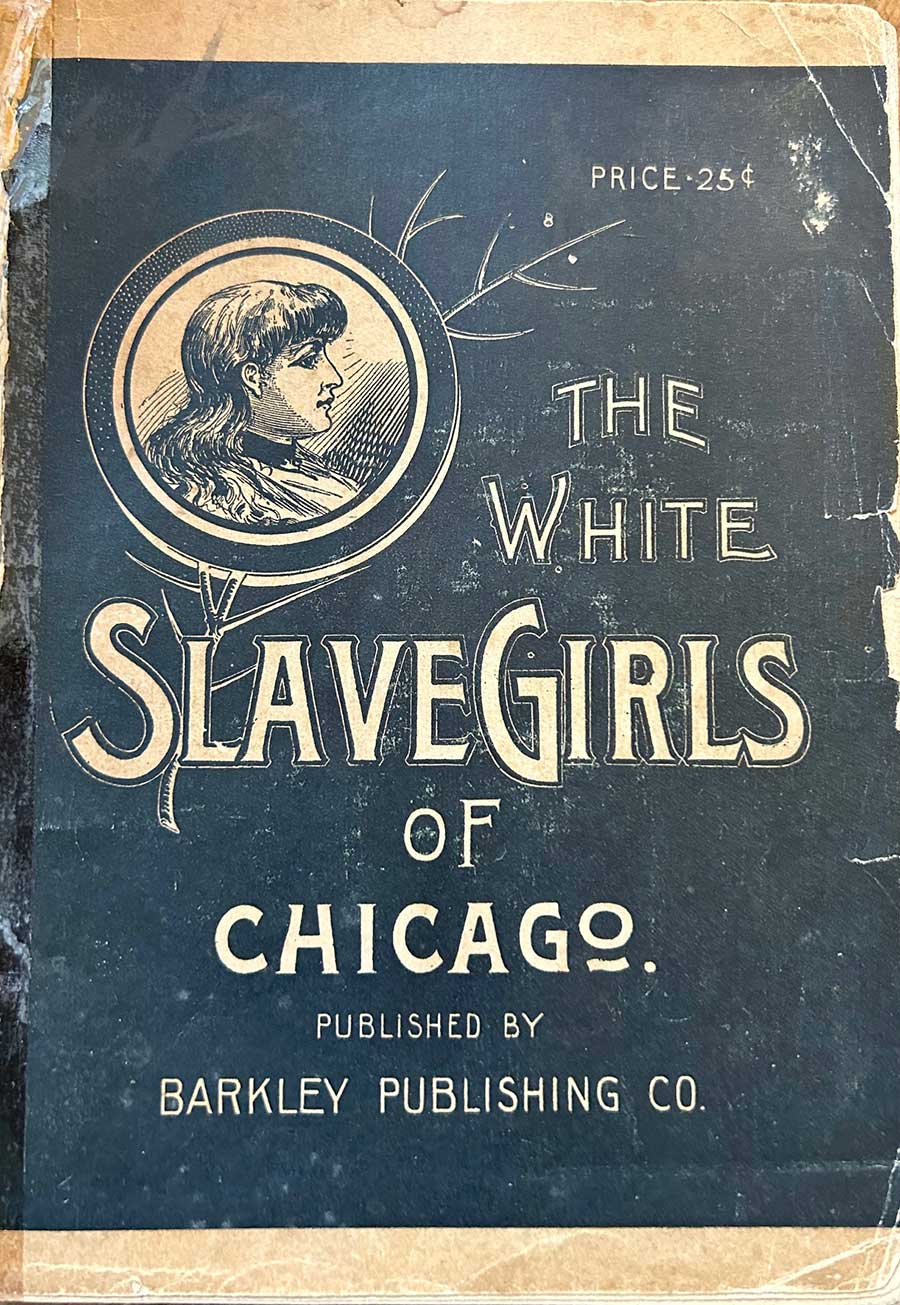

But whilst Bly and Black went on to become the highest earning women journalists of their day, another star rose and fell all too soon. Nellie Bly might have inspired with her sheer guts and steely determination, but it was Nell Nelson who won my heart with her powerful, no-holds-barred undercover reporting of the exploitation of the ‘White Slave Girls of Chicago’ – the poor immigrant women whose lives were worn away in deadening drudgery in the city’s overcrowded and foul-smelling sweatshops. A week’s wage for an average poor immigrant hand-sewer in the Chicago sweatshops was as little as $2.50 – for a ten hour day, six days a week. Nelson’s powerful series of exposés are filled with rage at this ruthless exploitation, which she witnessed at first hand working undercover in the sweatshops. They provoked considerable controversy and fuelled widespread campaigning for sweatshop legislation in Illinois State. An indignant Nelson summed up the complacency of the American ideal when viewed against the widespread system of exploitation and abuse she had witnessed over a six-month period:

The birthright of an American girl maybe a glorious attribute on the deck of a transatlantic steamship or the floor of a London ball-room, but it is not worth the flop of a brass farthing in the cloak factories of Chicago.

I re-discovered Nell Nelson in my research for Dark Hearts of Chicago, but she is still virtually unknown and unsung even in the USA, so much so that it took a while to find her real name, Helen Cusack, and I am yet to trace a single photograph of her. The sweatshop sequences in Dark Hearts would not be what they are without her trenchant news reporting.