The Last Days of Sydney Gibbes, English Tutor to the Tsarevich

“Strangely – having been highly reluctant for most of his life to talk about his time with the Romanovs – as he lay there sick and suffering Gibbes finally opened up about this life in Russia in some detail…”

Sydney Gibbes — Tutor to the Tsarevich

It was something of a tradition in the Imperial Family to have non-Russian tutors and nannies for their children. John Epps taught the children English during 1905–8; the Irish governess/nanny Margaretta Eager looked after the four sisters from 1898 to 1904. Nicholas II’s sister Xenia hired an English tutor, Herbert Stuart, for her six sons and Nicholas himself was devoted to the English tutor Charles Heath who oversaw his own eduction. But perhaps the best known of them all was the English tutor who taught first Anastasia and Maria and later Alexey the Tsarevich. His name was Sydney Gibbes.

The winter of 1962/3 was one of the coldest ever experienced in Britain. Bitter freezing conditions and a bone chilling easterly wind had brought heavy snow over Christmas, that had been accompanied by terrible, dense fog that had persisted well into the New Year. The now historic fog of 1963 took a terrible toll on the old, the frail and the vulnerable. At St Pancras Hospital in London (then part of University College Hospital) the nurses were overwhelmed with sick patients that dreadful winter. One such nurse who spent three months on the geriatric ward caring for the many elderly who had succumbed to the fog and the cold was Anne Scupholme. The death rate was very high: Anne, who, then aged 22, was the senior night nurse on her ward, recalled there was at least one death every night and on one occasion, three in a single night.

Fifty-five years later there is one death that still sticks in her mind. His name was Charles Sydney Gibbes, but since 1934, when he had taken his vows as a Russian Orthodox priest, he had been known as Father Nicholas. Under his real name he had been English tutor to the five children of Russia’s last Tsar and Tsaritsa – Nicholas and Alexandra – and during that time had developed a very close relationship with the young tsarevich, Alexey.

Sydney Gibbes (right) with Pierre Gilliard.

From 1908 until the revolution of 1917 brought the Russian throne crashing down, Gibbes had lived with the Imperial Family at their palace at Tsarskoe Selo, 15 miles south of St Petersburg. He had shared holidays with the family in Crimea and on board the Imperial yacht, sailing round the Finnish skerries. During World War I he had accompanied the young tsarevich to Army HQ when he joined his father there in 1916, in order to ensure he did not miss out on his studies. Left behind in St Petersburg when the Romanov family was taken to Tobolsk in Siberia in August 1917, Gibbes managed to join them there later, and followed them to their final place of arrest – in Ekaterinburg, Western Siberia – in May 1918.

But this time the Bolsheviks would not let Gibbes enter the house where the Romanovs were held captive. After the family were murdered there on 17 July 1918, he managed to retrieve a few precious mementos from the Ipatiev House. Then, like many others who had been closely connected to the Imperial Family, he fled the Bolsheviks on the Trans- Siberian Railway to China.

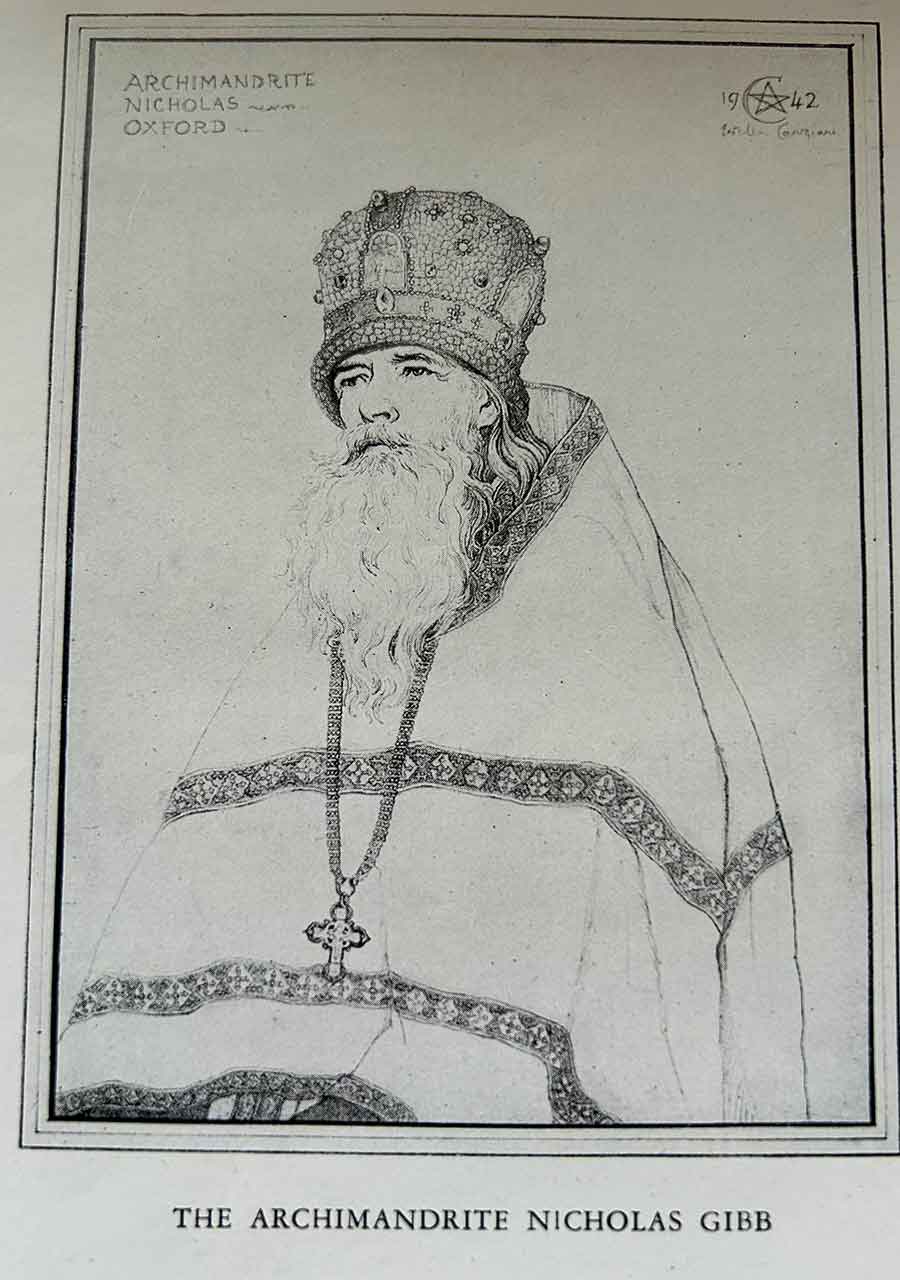

After living and working in Beijing as a secretary at the British Embassy, Gibbes eventually settled in Harbin, where he lived for the next 20 years working as a customs official. In 1934 he converted to Russian Orthodoxy and became a priest. During his time in China, Gibbes had visited England on occasion but did not return permanently until 1937. Now known as Archimandrite Nicholas, with snow-white hair and a long and venerable white beard, he was attached to the Russian Orthodox Church of St Philip on Buckingham Palace Road, but moved out of London during the Blitz and settled in Oxford. In 1949, he sunk most of his savings into buying a house in Marston Street where he created a chapel cum shrine to the Romanov family on the ground floor. Here he displayed the Romanov mementos he had managed to preserve and bring home from China in a collection of trunks and boxes, many of them personal gifts from the family. The chapel became a base for Gibbes’s own Russian Orthodox community of St Nicholas the Wonderworker.

Failing Health

In 1959 and now in rapidly failing health, Gibbes had finally retired from the priesthood to live in a house he owned at 17 Robert Street in London, making only occasional visits back to Oxford. The house was one of a row of seedy and dilapidated Regency houses off Camden Road (now demolished) that had seen better days. Here Gibbes occupied a tiny bed sitting room, sharing the rest of the house with a succession of students, most of them studying at the nearby Slade School of Art or University College London. Gibbes’s own room was extremely Spartan: divided into two by some hardboard nailed to battens, an opening from the outer section which measured a tiny 8’ x 4’, revealed an even smaller space containing his bed of hard planks, covered by coarse blankets. The outer space was dominated by a large stove, on which – as one of the student tenants, Jeremy Hornsby, recalled – a huge saucepan of cabbage soup was forever on the boil. In memory of his many years in Russia, Gibbes had also improvised a sauna for himself in a tiny cubicle with an electric heater perilously poised above him.

Archimandrite Gibbes

The students were often late with their rent, but Gibbes could happily be mollified by a couple of hours of chat, recalled Hornsby. He vividly remembers the thin, hunched old man in his flowing beard and his soiled black robes, who often sat happily typing away – probably at memoirs of his time with the Romanov family. On the wall behind him hung six magnificent icons. Gibbes told him that they were ‘the last presents that the Russian Royal Family gave him’ before they left for Ekaterinburg. Hornsby noticed that on each of the icons, ‘long slivers of black oil had run down to deface the remarkable artistry’. No doubt this was from years of having small oil icon-lamps burning in front of them. But to Gibbes they were a powerful spiritual reminder of his time in Russia: they were ‘the spirits of the Tsar and his family making their presence known through the icons’.

It was here in this small and rather squalid refuge that Gibbes was found in March 1963, alone and having suffered a stroke that was soon followed by pneumonia. The walls of his self-created monk’s cell were covered with old blankets and furs against the cold, but that had not prevented him from succumbing to the terrible winter conditions. He was brought to St Pancras Hospital not far away and placed under the care of nurse Anne Scupholme. From the first she noticed how very eccentric he was. Strangely – having been highly reluctant for most of his life to talk about his time with the Romanovs – as he lay there sick and suffering Gibbes finally opened up about this life in Russia in some detail. Perhaps in her presence and that of the young students at Robert Street he had finally felt a need to let go of things long suppressed. As Anne Scupholme recalls – ‘he was confused but shared many tales from the Russian Court with me, although I had difficulty believing them at the time.’ It was only after he died on Anne’s shift, that she discovered, from an obituary in The Times the next day for ‘Archimandrite Gibbes, Tutor to the Russian Royal Children’, that the stories were true. More than half a century later, Anne vividly recalls that Gibbes’s first and foremost dislike was of Rasputin, whom he ‘blamed for Alexandra’s ill health and therefore that of Alexey’. He had ‘rather liked living at the Russian court and had seemed oblivious to the unrest outside.’ His bitterness toward the Russian peasant was intense: he thought all peasants were ‘uneducated, ungrateful and should have remained subservient in gratitude.’ These, according to Anne, were ‘clear and consistent themes in his night-time ramblings’. But what she was not so clear about was ‘why he would suddenly turn on me in a rampage about how it was me, and my kind, who had killed the tsar and Alexey’. Gibbes repeatedly, and bitterly, blamed the British royals for not rescuing the Romanovs. Anne adds that he never talked about women except the tsaritsa, and only in terms of her relationship with Rasputin. She sensed that he had little interest in the women in his story – ‘but whether this was a product of his upbringing or a general dislike of women’, she did not know; passing suggestions about Gibbes’s private sexual preferences have never been substantiated. What sticks in her mind is that although Gibbes could be difficult and at times became exasperated with her and all the other nurses, he was clearly suffering the mental confusion of a dying man. There were times when he reached out to her: ‘he was always very reluctant to let go of my hand’, she remembers, and it was a hand with a remarkably strong grip for someone so sick.

At some point shortly before Gibbes died, a Russian Orthodox priest came to give him the last rites. He also insisted that the nurses should do nothing to his body when the moment came. ‘This all happened a long time ago but I can still see the bed and its position in the ward very clearly,’ recalls Anne. ‘The detailed instructions for laying out his body after death had clued me in to the fact that he belonged to someone, somewhere and that some of his conversation was based on fact.’ But she herself never saw any visitors; ‘he seemed to be alone, with no family’. (He did in fact have an adopted son living in Oxford).

Charles Sydney Gibbes died at the age of 87 at around 5.30 am on 24 March 1963, Anne Scupholme’s shift had ended at 8, so she was not there when his body was laid out according to Russian Orthodox practice. Gibbes’s funeral was held on 28 March at the Russian Orthodox Church at Ennismore Gardens in Knightsbridge; his coffin was then taken back to Oxford where he was buried in Headington Cemetery, the simple gravestone marked by a traditional Russian Orthodox cross.

In 2010, Gibbes’s community of St Nicholas the Wonderworker, which for years had been meeting in a church hall, finally acquired its own premises – in a disused Anglican church in Headington Oxford. This is located not far from Gibbes’s original chapel, and now has a thriving community of worshippers. The collection of precious Romanov artifacts that Gibbes brought back with him from Russia – including an icon from the Tsaritsa, a pair of Nicholas II’s felt boots, the Tsarevich’s pencil case and exercise books belonging to his sisters Maria and Anastasia, and the beautiful Italian Murano glass chandelier of red and white lilies that he retrieved from the Grand Duchesses’ room of the Ipatiev House in Ekaterinburg were once on display at his chapel in Oxford. They have since disappeared into storage and their whereabouts are uncertain. In 1986, Gibbes’s adopted son George Paveliev Gibbes, sold off two of the most important Romanov pieces in his father’s collection made by Fabergé: a pair of monogrammed cufflinks given to Gibbes by the tsar’s eldest daughter, Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna, and a miniature gold Easter egg pendant with a diamond in the A note, that belonged to Anastasia. The latter was bought by film maker Steven Spielberg as a gift for his then wife, Amy Irving, when she finished filming at TV mini series starring as Anastasia.