Mr Heath

“Many people have heard of Sydney Gibbes, the English tutor to the children of Nicholas and Alexandra, but how many are aware that Nicholas himself had a much-loved English tutor, Charles Heath?

Mr Heath or ‘The Old Man’ as the Romanovs affectionately called him had a formative influence on Nicholas’s young life and is the subject of the latest episode in my Stories From the Footnotes of History”

Mr Heath – The English Tutor who Taught Tsar Nicholas II to be the Perfect Gentleman

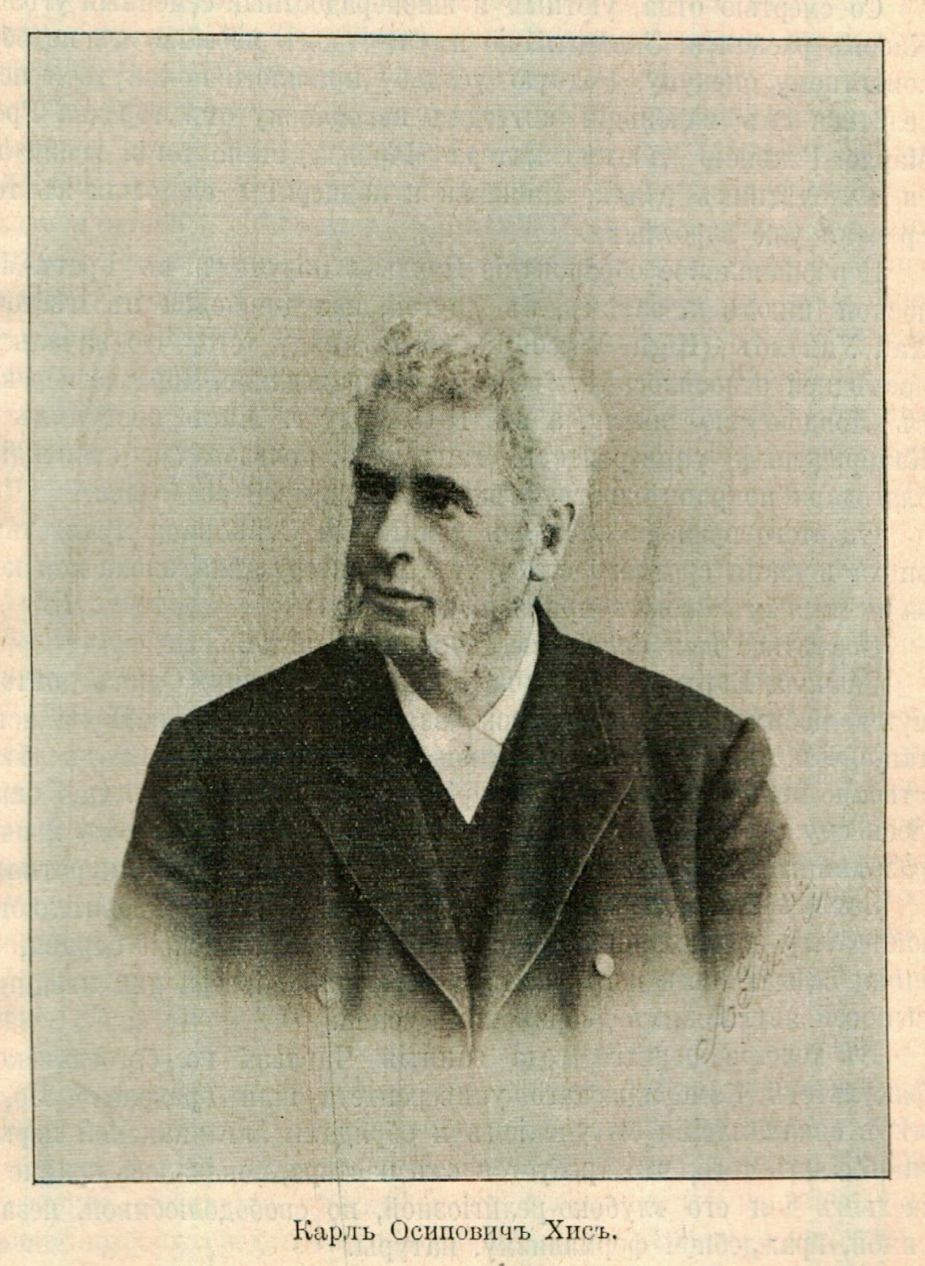

Imagine if you will a combination of the revered head of Rugby School in Tom Brown’s Schooldays (1857) and the loveable schoolmaster in Goodbye Mr Chips (1934) and you will have a fair idea of the qualities of the modest, self-effacing man who taught the last tsar of Russia the best of moral values, encapsulated in the ‘play up and play the game’ ethos of the British public school. Throughout his teaching career, Charles Heath, or Karl Osipovich Khis, as he was known in Russia, held to this ethos. His insistence on truthfulness in all things could not have been better exemplified than in his devoted mentoring of his star pupil, the Tsarevich Nicholas Alexandrovich, to whom he was appointed English preceptor and assistant governor in 1877.

From Great Marlow to St Petersburg

Heath’s story begins at Great Marlow in the Buckinghamshire countryside in 1826, where he was born to a gentleman farmer, Joseph Heath and his wife Susanna. For six generations the Heath family had been wealthy landowners at the beautiful historic village of Ewelme in Oxfordshire, famous for its connections to the Chaucer and De La Pole families.

During his quiet rural childhood Charles developed a passion for the outdoors – for fly-fishing, hunting, riding and shooting and after being educated at schools in High Wycombe and London, he began searching for a vocation. At first he thought of training as a doctor but his widowed mother set her sights on him becoming an Anglican priest and so he went up to Cambridge to study Theology. But he hated the rigid formalism of his studies and left after only two terms (1848-9). The next best option for a young man of his class was some kind of government service abroad – perhaps India. But by 1850 Charles Heath had other thoughts in mind: he wanted to go to Russia.

He had seen an advertisement in a newspaper for an English tutor to teach at a pension in St Petersburg run by a certain Vilyam Mechin (a Russianized German). On attending an interview in London clutching a sheaf of testimonials Heath was asked ‘what do you know and what can you do?’ to which he had replied: ‘I know my native language and its literature, and also mathematics. I have studied the Classics and I speak a little French. I can ride any horse, shoot, swim, row – I won rowing prizes at university races – and I can fish and play cricket.’ In short, he was young, he was energetic and he was eager. These seemed the perfect prerequisites and soon after Charles was on the steamship to Kronstadt.

The Pension Mechin in St Petersburg was a first-rate preparatory school for the sons of the Russian aristocracy and from the moment he arrived Charles found himself moving in circles far removed from those he had occupied back at home in the Buckinghamshire countryside. He quickly demonstrated unique qualities as a teacher that would be remarked on by many over the years to come. First and foremost he had a great and abiding love of children and an innate understanding of the mind of the child; he had a natural ability to inspire in them a sense of loyalty and trust and had an instinctive and progressive way of teaching that did not stifle their individual development. Unlike many of his colleagues, Heath never insisted on a pedantic routine and all his teaching was infected with his natural good humour. Unfortunately his time at the Pension Mechin was cut short when Mechin, having been invited to teach English to the Grand Dukes Alexander and Vladimir Alexandrovich and assist in the education of their younger brothers Sergey and Paul, closed the school.

“First and foremost he had a great and abiding love of children and an innate understanding of the mind of the child; he had a natural ability to inspire in them a sense of loyalty and trust and had an instinctive and progressive way of teaching that did not stifle their individual development”

Teacher at the Alexander Lyceum

For a while Heath gave private lessons. Unfortunately little is known of those first six years in Russia, during which – between 1854 and 1856 – Heath’s home country Great Britain was at war with Russia. He seems not to have suffered or been ostracized for being a British national in Russia at the time; indeed, he was by now a leading light in an expatriate English Debating Society which was allowed to continue meeting during the war, and was a co-founder of the exclusively English Fishing Club that met on Harraka Island off the coast of Finland. In the meantime, Heath’s reputation as a pedagogue had grown, so much so that in November 1856, he was invited to join the staff of the Alexander Lyceum on Kamennoostrovsky Prospekt, the premier, exclusive boys’ school, where Russia’s future diplomats and high officials were educated.

“There was no doubt he had a heart of gold, making a point of treating all his pupils equally and getting to know each boy individually. He inculcated in them a sense of honour and fairness, and above all taught them always to tell the truth.”

The Importance of Health & Fitness

But it wasn’t just his passion for English literature that Heath passed on to his pupils, it was also an attention to physical hygiene and fitness, and an insatiable love of sport and fresh air, being a great believer in their character-forming influence. He taught his boys boxing, fencing, rowing and croquet. He introduced cricket to the school, gave up his Sundays off to take pupils on long bracing walks, and in all things exhorted them to have the courage to play hard, and fair, and tolerate pain. A man of many talents, he was also an accomplished watercolourist and gave classes in drawing and painting; he constantly doodled in class and many of his students kept this work as a memento of him.

Tutor to the children of Tsar Alexander II

Through his contact with Mechin, and while still teaching at the Alexander Lyceum, Heath appears to have been invited some time in the 1860s to tutor the younger sons of Alexander II – Grand Dukes Sergey and Paul – in English and also to teach watercolour painting to their sister Maria Alexandrovna, (who apparently continued to receive lessons from Heath until she left Russia after her marriage to Queen Victoria’s second son Prince Alfred in 1874). He also taught English to the three youngest sons of Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich.

But it was not until 1877, when he was already in his fifties, that Heath finally took on the most important role of his career – teaching English to Nicholas, eldest son of the future Alexander III, his brother George and eventually their younger brother Michael. Once established in the post he was invited to move his family to Gatchina where they were provided with a comfortable apartment.

Heath also taught watercolour painting to Nicholas’s younger sister Olga – she noting that the ‘dear old man’ painted daily and with great rapidity, tearing up his work as he went along if he didn’t like it (and which she often rescued from the waste bin). As a member of the Society of Russian Watercolourists, Heath exhibited and sold his work in St Petersburg and sent paintings back to England to be shown at the Dudley Gallery in London’s Piccadilly.

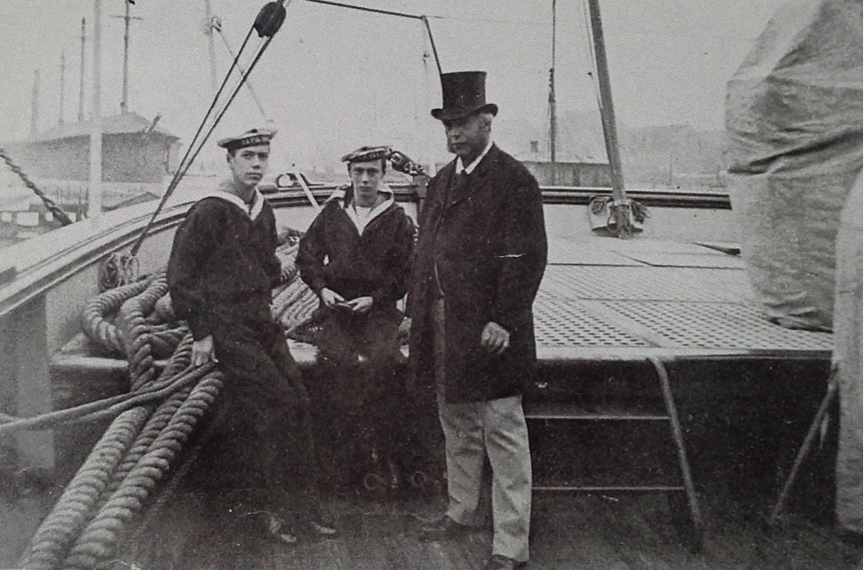

Alexander III of Russia,Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich Romanov of Russia,Marc-Ferdinand Thormeyer (French tutor) and Charles Heath (English tutor)

Неизвестный, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Educating a Future Tsar

When it came to the education of Nicholas Alexandrovich, before and after he became tsarevich of Russia, it is clear from all that we know of Heath’s principles and practice that it was he who was responsible for Nicholas’s acquisition of an impeccable English accent and faultless fluency – both of which were frequently noted wherever Nicholas travelled abroad. Indeed, it was suggested by the historian Sergey Tatishchev, in a tribute made after Heath’s death, that his influence over Nicholas was very similar to the formative influence of the Swiss tutor Frédédric César de la Harpe over Alexander I and the Russian poet Vasily Zhukovsky who was tutor to Alexander II.

Nicholas’s Anglophilia and his fluency in English later became important factors when, for pressing political reasons, the British and Russian royal families aligned more closely with each other and distanced themselves from Germany during the 1890s. But Heath not only inspired in Nicholas a lifelong love for the English language and its literature and history, introducing him to a wide range of writers from Bacon to Byron, he encouraged a love of reading out loud. This was exemplified during the Imperial Family’s difficult months in captivity after the Revolution when Nicholas read many of his favourite English novels to the family to help stave off the crushing boredom of their imprisonment. Above all, Heath taught the future tsar to be a decent human being; to be honest and fair and in all things to exercise that very particular English stiff upper lip which was his own watchword.

One of the first things that had struck Heath when he began his duties with the young Grand Duke Nicholas was that he was not taking enough exercise. It was undoubtedly Heath who sowed the seeds of Nicholas’s prodigious physicality, probably teaching him to swim (in 1879 Nicholas had admitted to his father that he still could not do so), encouraging what became a remarkable appetite for long walks, and imbuing in him a love of sport and exercise, that extended also to his siblings and eventually Nicholas’s own children. In around 1881, again thanks to Heath’s initiative, a gymnasium with horizontal and parallel bars was installed at Gatchina. Accounts of Nicholas in captivity note that right up until and including his incarceration at Tobolsk he was fanatical about exercising daily on parallel bars and doing chin ups.

‘Aristocrats are born but gentlemen are made’

Heath later recalled how hard Nicholas had worked to control his temper, even as a child. If he had a quarrel with his brothers when playing, ‘in order to restrain himself from saying or doing something unkind, he would go in silence into another room, pick up a book and only come back when he had calmed down to take up the game again, as though nothing had happened.’ This self-restraint became a marked feature of the tsar, as General Vladimir Voyeikov, who worked closely with Nicholas at Russian Army HQ during his final years, noted. ‘One of the Emperor’s outstanding qualities was his self-control’, he recalled, and it was clear he had ‘worked hard on himself from his childhood under the direction of his tutor, the English Mister Heath, and had achieved a tremendous degree of self-possession.’ It was Mister Heath, too, recalled Voyeikov, who had ‘frequently reminded his imperial pupils of the English saying that aristocrats are born but gentlemen are made.’

Heath’s careful molding of his pupil’s character during his most formative years and his tuition in how to behave towards his fellow human beings must have gone some way in contributing to Nicholas’s innate charm, his courtesy and his truthfulness. In short, Heath taught him to be the Perfect English Gentleman. Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna always remembered him with the greatest affection, and how Heath taught the imperial children to fish, to row, to ride ‘to play games and never to cheat.’ He was a ‘dear, honest, gentlemanly soul’, she told a member of the Heath family in 1959, ‘one of our best friends from early childhood until his death.’ To them he was simply Karl Osipovich or more affectionately, ‘Old Man’.

Charles Heath’s Devotion to the Romanov Family

There is no doubt that Heath had a deep and abiding love not just for Nicholas but also the imperial family as a whole and remained as devoted to them through his many years of service, as he was to his own family. Alexander III and his wife Maria Feodorovna looked upon Heath as a personal friend, so much so that the tsar often invited him to accompany the family on sailing excursions round the Finnish skerries, staying at the Imperial fishing lodge at Langinkoski and taking pleasure in cooking al fresco meals with them.

A Visit to Queen Victoria

Such was the Tsarevich Nicholas’s respect for Heath that in the summer of 1894, shortly after his engagement to Princess Alexandra of Hesse, he invited Heath to accompany him to England and took him to meet Granny – Queen Victoria. The queen found the genial and bewhiskered Heath ‘kind and plain spoken’ and entertained him to dinner. She spent some time chatting to him, during which she noted that Heath had spoken ‘in the highest terms of Nicky, who he said was excellent and true’.

Heath’s close relationship with Nicholas and the Imperial Family continued after Nicholas’s accession in November 1894. By the time he retired, Heath had been promoted through the tsarist table of ranks to Councillor of State, and awarded numerous medals and honours for his long and faithful service, including the Order of Vladimir. But he had always been indifferent to awards and lived a quiet and contented life with his family.

In 1889 Heath had begun suffering from heart disease and when he became seriously ill at the beginning of 1900 the Dowager Empress sent him to the Imperial Fishing Lodge at Langinkoski to rest and recuperate under the care of Dr Nikolay Kalinin, from the city hospital at Gatchina.

Laid to Rest in St Petersburg

On his return Heath retreated to his apartment in a building on the Fontanka in the grounds of the Anichkov Palace where he died on 2 December 1900. An impressive Anglican funeral service was arranged for him at the English Church in St Petersburg, attended by a considerable gathering of Russian dignitaries and court officials, after which the Dowager Empress, Grand Dukes Konstantin and Mikhail Alexandrovich, Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna, and Alexander Georgievich, Duke of Leuchtenberg followed the coffin to the Smolensky Cemetery for burial. Nicholas II unfortunately was absent, lying sick with typhoid fever at the Livadia Palace in Crimea at the time. The news of Heath’s death was reported in The Times, which noted how the ‘great number of costly wreaths in silver and flowers from the Tsar, the Empress, the Grand Dukes, the British Ambassador, and others, with many touching inscriptions, testified to the affectionate esteem in which Mr. Heath was held by the Russian Imperial family and a large circle of friends.’

Charles Heath’s artistic legacy

Not long after Heath’s death, 239 of his watercolours were put on sale to raise money for a bursary in his name to be established at a home for the care of poor and sick children at Gatchina. Years later his watercolours – especially those painted in the Finnish skerries – were still sought after. Today, the Russian Museum in St Petersburg holds thirty-one watercolours and drawings by Heath and the Hermitage holds many more.

British journalist William Barnes Steveni, who visited Heath many times at his apartment at the Anichkov Palace recalled how he showed him his autograph book which contained, ‘among various distinguished signatures and writings’ a quotation written and signed by Nicholas II:

‘To thine own self be true, and it must follow, as the night the day, thou canst not then be false to any man.’

It is the perfect summary of what Nicholas felt he had learnt from his beloved English tutor. ‘Simple, unaffected, frank, straightforward, and manly’, as another journalist W. T. Stead remembered him, Charles Heath had always taught his pupils that ‘A man’s happiness may be measured by the amount of happiness which he confers on others’. It was a belief that the altruistic Heath clearly lived by, and one for which Russia’s last tsar, Nicholas II, undoubtedly remembered him.

A fuller version of this article can be found in Royalty Digest Quarterly 2016 no 2, pp. 10–16. My thanks to Rudy de Casseres for his invaluable help in tracking down Charles Heath’s paintings in St Petersburg.