John Reed: Writing the Russian Revolution

“John Reed was the archetypal rebellious romantic. He was made for revolution and hungry for a cause and the Russian Revolution found its most passionate American advocate in him”

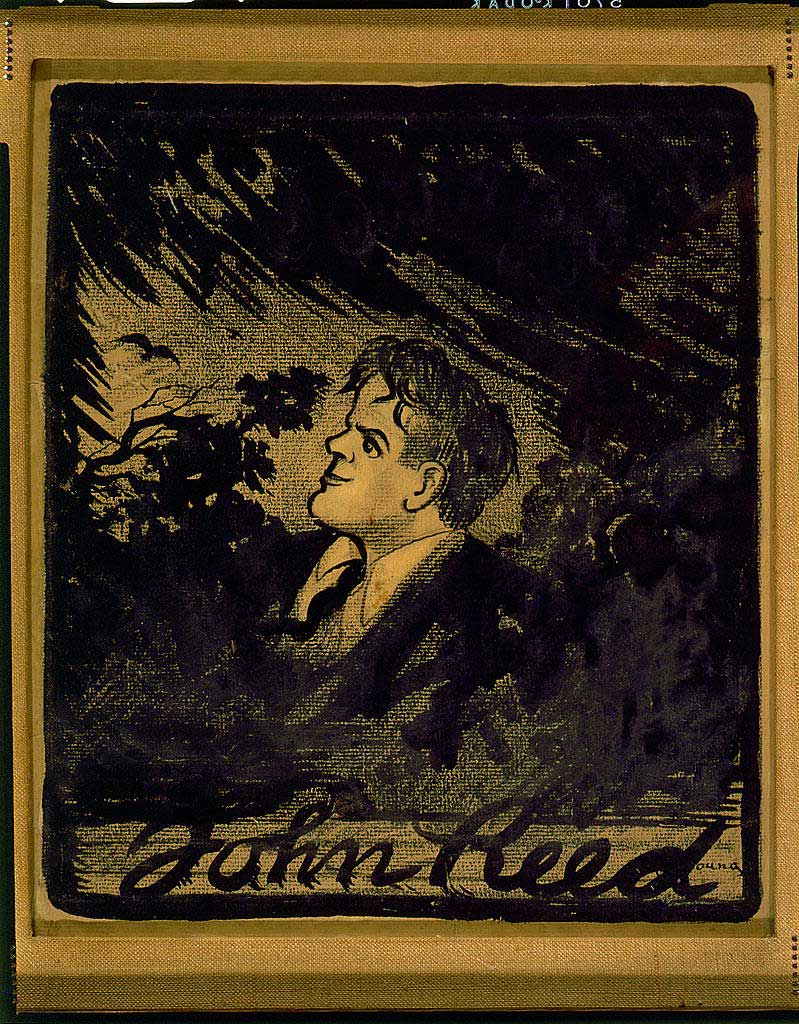

John Reed — An Archetypal Romantic

John Reed, American journalist and Communist activist – taken between 1910 and 1915

Returning to New York in 1916 he continued writing inflammatory political articles in the radical press. That autumn he met and married the feminist journalist Louise Bryant. When revolution broke in Russia in February [OS] 1917 Reed was determined to be a witness of this great new Socialist utopia-in- the-making, and set about raising the money to fund his trip there with Bryant. The couple finally arrived in early September, somewhat late for the party, having missed the popular street protests of the very violent February Revolution; the struggles of the Provisional Government to hold on to power; the resumption of violence in early July; and the crisis of the Kornilov revolt at the end of August.

Reed had a lot of catching up to do and was at a distinct disadvantage from other foreign journalists already there, in that he arrived without any contacts or knowledge of the city. He went straight to the US Embassy on Furshtatskaya Ulitsa with a letter of recommendation for the US ambassador David R Francis, which, somewhat unconvincingly asserted that he and Bryant were ‘visiting Russia with a view to studying conditions’. The letter asked that the ‘gentlemen of the Embassy’ should extend any help and courtesy they could to them, but Francis was instantly suspicious. He was well aware that Reed was a notorious radical accredited to the New York left wing press. Here was no innocent ‘visitor’, but a reporter with a clear political agenda. Francis deemed him a ‘dangerous Red’ and had him watched.

Reed’s unrepentant sympathies for the revolutionary cause and his championing of the victory of the masses ensured that from the first he would be an outsider in the expatriate community of Petrograd. He and Bryant never became integral members of that closed and clannish world, which was highly suspicious of their politics. Nor for that matter did other American, British and French journalists already operating in the city welcome them with open arms. Seasoned reporters in the Allied press circle, such as Arthur Ransome of the Daily News and Harold Williams of the Daily Chonicle, had been in Petrograd for some time, spoke fluent Russian and knew their way around. Unlike Reed with his burning socialist passion, they were far more sanguine about the realities of the new revolutionary order and its political players.

Reed’s wife Louise Bryant, undated, circa 1917

Because Reed and Bryant’s radicalism instantly alienated many in the US colony, during their time in Petrograd they stuck to their own tight coterie of fellow travellers. Immediately on arriving they met up with two other US radicals and reporters who had already been in Petrograd for several months. Albert Rhys Williams, a congregational preacher whom Reed had known in Greenwich Village, was there for the New York Evening Post, and Bessie Beatty had arrived in June, reporting for the San Francisco Bulletin. For the remainder of their time in Petrograd this quartet of like-minded socialists experienced events unfolding in each other’s company, so much so that Beatty would later dedicate her memoir The Red Heart of Russia to ‘The Four Who Saw the Sunrise’ – a dedication that, sadly, has not stood the test of time.

Intellectually privileged they might have been, but Reed and Bryant were broke and cold for most of that winter of 1917-18. They could not afford a hotel and so, holed up in an unheated flat and enduring food rationing like everyone else, they slept in their overcoats. But they lived through that desperate winter with an intensity shared by few other writers. Through Rhys Williams, Reed gained the good offices of a Russian-American interpreter, Alexander Gumberg, who accompanied him round Petrograd. Gumberg, however, quickly became disenchanted with Reed’s partisanship and what he saw as a bombastic espousal of the revolutionary cause. For him this over-enthusiastic American was an ‘irresponsible romantic’, an Ivy League ‘preppie’ playing at revolution.

While the expatriate Brits and Americans remained highly skeptical about the viability of the Provisional Government and in the main deeply hostile to the Bolsheviks, John Reed threw himself into the cauldron of events. He joined Bolshevik patrols and propaganda drives, riding round the city in open trucks, tossing out leaflets from the back. It was ‘a silly and florid performance’ in the view of Edgar Sisson, based with the US Committee on Public Information in Petrograd.

“Sisson decided to have a serious talk with Reed: he told him that ‘he should have experience enough to know that he was being used by the Bolsheviks for advertising purposes.’ Reed shrugged it off: he was ‘only looking for writing color’, he told him.

But for other Americans in the city, Reed and Rhys Williams’s courtship of the Bolsheviks was tantamount to treason: they were, after all, US passport bearers, issued under an oath of loyalty to their country, the protection of which they both claimed.”

Reed’s coming of age as a writer

Leighton Rogers, a young college graduate who had been sent out to Petrograd in October 1916 to help set up a branch of the National City Bank of New York, was equally appalled. Like Alexander Gumberg he thought Reed a dilettante. He was said to ‘be something of a poet’ Rogers noted, and ever since arriving had been ‘milling around Petrograd playing revolutionary’. ‘I’ve seen him riding in trucks tossing out Red handbills and posing conspicuously beside speakers at Bolshevik street corner meetings,’ he wrote, but at a time when America had entered the War and all Rogers’s friends back home were joining up, it infuriated him to see this ‘arrogant poseur aiding the Bolsheviks’ by supporting their calls for a separate peace with Germany. ‘When I think of the good young Americans who will have to bear the brunt of the massive German attack that is surely coming in France, using troops transferred from the Russian front, when I think of how many of them will be killed my blood boils at the thought of John Reed,’ Rogers wrote in his diary. ‘He has been helping the Russian Reds against the interests of the United States by every available means.’

Reed cared not a jot about how his compatriots viewed him and relished every moment of the dramatic events he witnessed. He wrote to a friend in New York that he had more material than he could ever have time to write about. ‘We are in the middle of things, and believe me it’s thrilling’. Emotional, provocative, uncompromising, Reed could not live the Petrograd experience by halves. It had seized his imagination:

“‘For color and terror and grandeur this makes Mexico look pale,’ he wrote. He was full of questions and wanted to ‘see everything at once’ and meet and converse with real Russians. In Petrograd he noticed that ‘every street-corner was a public tribune’. Russians ‘got drunk on talk,’ and he thrilled to conversations that were, to him, ‘pure Dostoevsky’.”

Despite his poor health, Reed drove himself relentlessly, attending all-night sessions of the Petrograd Soviet; accredited as he was to radical publications back home in New York, the Bolsheviks treated him differently to other foreign reporters and granted him unique access to their debates and their leaders. This took Reed closer to the heartbeat of revolutionary politics than almost every other foreign reporter in the city; indeed, he was one of the few of them after the October Revolution who was able to work effectively, given the vagaries of the telegraph and postal systems.

Revolution undoubtedly was, as his friend Rhys Williams said, Reed’s coming of age as a writer. Ten Days that Shook the World bursts into life in his accounts of the turbulent, hothouse atmosphere of the Petrograd Soviet, where Reed transforms the tedium of Bolshevik politics into high drama, and produces some fine, intense writing that captures the frenetic atmosphere of the moment.

“At the Smolny, which he said ‘hummed like a gigantic hive’ the lights blazed, the ‘committee rooms buzzed and hummed all day and all night, hundreds of soldiers and workmen slept on the floor, wherever they could find room.’ Upstairs in the great meeting hall there was ‘no heat but the stifling heat of unwashed human bodies. A foul blue cloud of cigarette smoke rose from the mass and hung in the thick air. … The congress boiled and swirled … the delegates screaming at each other as a reckless daring, new Russia was being born.’”

Louise Bryant at husband John Reed‘s funeral.

But the hotheaded Reed would not be persuaded from further alienating American opinion in Petrograd. Despite Edgar Sisson’s warning not to take part in the 3rd All Russian Congress held in January 1918, Reed attended along with Rhys Williams. Sissons was unimpressed: with their bad Russian they both ‘made a sorry, stammering show of themselves’. By now Reed’s wife Louise had returned to New York and in early February Reed followed her, perhaps already having sensed that the new Socialist Utopia in Russia was not quite what he had expected it to be. In October 1919 he was persuaded, somewhat against his better judgment, to return but contracted spotted typhus in Moscow and died there on 17 October 1920. Fellow ardent socialist and journalist Lincoln Steffens, who had also been an eye witness of Petrograd 1917, thought Reed’s death in Russia most apposite. He had ‘become living and dying proof that “all roads in our time lead to Moscow”’. For a while Reed’s ashes were accorded the honour of being placed in the Kremlin Wall, but some time in the 1960s they were quietly removed to a collective site behind the Lenin Mausoleum.

Handsome, charismatic and spoiled, John Reed never quite grew up, in the view of Edgar Sisson. Nor did he ever transcend his defining account of the October Revolution in his writing. Ten Days That Shook the World would become the gold standard of eyewitness reporting on Russia in 1917 for a century to come. In 1981 Reed’s image as romantic revolutionary was irrevocably set in stone by Warren Beatty’s Hollywood film Reds. Together, they have ensured that, by a strange irony, the most enduring international image of the Russian Revolution would be the work of an American journalist, and not its Russian protagonists.