Thomas Hildebrand Preston, 1886-1976:

The British Diplomat who tried to

Save the Romanovs

In later years Preston wearily repeated that despite his best efforts, he had been “powerless to intervene” in preventing the murder of the Romanovs in July 1918. He had in fact concluded prior to that with the greatest regret that “any attempt to kidnap the Royal Family and rescue them would have been an act of madness and fraught with the greatest danger to the Royal Family themselves”.

The popular TV history market has always had an insatiable appetite for royal stories, especially those about the Romanovs and the mythical, and now disproved, claims that Grand Duchess Anastasia survived the massacre at Ekaterinburg. With the spurious claims of Anna Anderson aka Franziska Szankowska finally put to bed, programme-makers still tend to fall back on the same tired claims that it was ‘all King George’s fault’ for not granting the Romanovs asylum in the UK. Over the years, the popular TV and film presentation of the murder of the Imperial Family often couples the condemnation of King George with swipes at the British ambassador in Petrograd, Sir George Buchanan, for also not having done more to try and help. Two recent examples play to the same old scenario: episode 6 of Season 5 of The Crown – entitled ‘Ipatiev House’ – and episode 4 of the Sky History documentary The Royal Mob about the four Hesse sisters, one of whom was the murdered Tsaritsa, Alexandra. While criticising the much-contested failure or otherwise of George V and Buchanan, none of these programmes mention the crucial role played by Thomas Preston, the British Consul in Ekaterinburg, in doing his best to help the Romanovs and in alerting the Allies to their perilous situation; Russian sources give him little or no credit at all and even, quite bizarrely, accuse him of betrayal.

Thomas Preston’s Early Life in England

Little is known of Preston’s early life and career, prior to his involvement in the Romanov story. He still doesn’t have an entry in the British Dictionary of National Biography and if you search the internet for information, you will find disappointingly little. His brief obituary in The Times in 1976 says virtually nothing beyond the bald statement that he was educated ‘at Westminster (school) and Trinity Hall, Cambridge’. He was born in 1886 in Epping, Essex, the son of William Thomas Preston (1858-1903) who was the second son of Sir Jacob Preston, a baronet of Beeston in Norfolk. The unusual middle name Hildebrand is a family name on his mother’s side. Thomas’s father had a brief army career between 1877 and 1881 as a 2nd Lieutenant in the 75th Foot, later the Gordon Highlanders. But in August 1881 he was ‘superseded for absence without leave’ – i.e. dismissed – the precise reasons unknown, which explains why his son Thomas makes no mention of this in his autobiography Before the Curtain.

In around 1894 William Preston tried to take up farming at Timaru on New Zealand’s South Island for a couple of years, but the venture failed and he brought his family back to England; on the April 1901 census the family was living in a boarding house in Richmond in reduced circumstances. By December 1903 William was dead at the age of only 45, having tried his hand at mining, with a license ‘to prospect for minerals and precious stones in a tract of land in the Soudan’ and apparently collapsing with heat stroke there. This left young Thomas obliged to leave the expensive fee-paying Westminster School. It was however, important to his mother that he have an education appropriate to a ‘gentleman’ and in 1905 he went up to Trinity Hall Cambridge to study Modern Languages. Sadly he dropped out after only two terms, probably for financial reasons and the need to help support his widowed mother Alice and three sisters. There was talk of a job in the city but Alice balked at the idea: ‘could not something be done for Tom at the Foreign Office?,’ she asked?

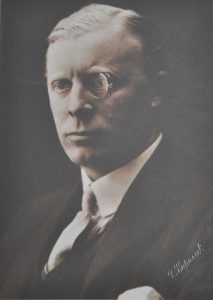

Thomas Preston wearing his signature monacle

Early Diplomatic Career in Batumi and Mining in Dzansoul and Siberia

Thanks to family connections on Alice’s side, Preston was offered the chance of going to Batumi on the Black Sea coast of Georgia, to take up a junior post at the consulate there with her cousin, Patrick William Joseph Stevens. He had served at the consulates at Odessa and Sevastopol in the 1890s before being appointed HM Consul for Baku and other provinces in the area, based at Batumi. Several other members of the Stevens family had served as diplomats, among them Patrick’s father George Alexander, who had been Vice-Consul in Kherson, southern Ukraine in the 1870s and an uncle Francis Illiff , who was Consul at Erzurum in Turkey during and after the Crimean War. Since the 1890s Patrick Stevens had been running British intelligence in the Caucasus.

In around 1907, after 18 months at Batumi, Preston was sent to the offices of the Dzansoul copper mine and smelting works high in the Caucasus mountains 40 miles south of Batumi (now Murgul in Turkey). It was a tough, rough-and-ready existence among seasoned drillers and engineers where the ‘out of hours distraction’ as Preston wrote, was to be found ‘mainly in gambling, drinking, and quarrelling’. After a year or so, he had had enough and accepted the offer from a New Zealander named Robinson, who had previously worked in the mining industry in Transvaal, South Africa, to join him on a gold and platinum mining expedition to Siberia.

We don’t know exactly when he left England but an article in the Mining Journal briefly described Preston and Robinson as shareholders in ‘An English enterprise in Siberia’ which was prospecting for gold in the Berezov region. This presumably is the same enterprise as the Nerchinsk Gold Mining Company, established in 1906, for which Preston is listed as a member of the committee in 1909 and had risen to director by 1911.

Return to Diplomatic Work at Batumi and Ekaterinburg

By that time Preston had returned to the consulate at Batumi with the area becoming strategically important in the run up to World War I, having been annexed by the Russians after the Russo-Japanese War of 1904. Batumi was now a major export point across the Black Sea to the Bosporus and the Mediterranean for the oil refined into kerosene sent by newly constructed pipeline west from the oilfields at Baku on the Caspian Sea. Much of it was shipped out on British tankers owned by Shell and one of Consul Patrick Stevens’s key roles was to keep an eye on its transit out of Batumi, as well as on Russian troop movements in the area. There is no doubt that Preston would have received training from him in local intelligence-gathering that he would exploit when he was offered the post of Vice-Consul at Ekaterinburg in May 1913. His fluent Russian and useful contacts in, and familiarity with, Siberia made him perfect for the job, responsible as he was for a swathe of territory from Perm in the Western Urals to the province of Akmolinsk in the east (now in today’s Kazakhstan).

Thomas Preston in British diplomatic uniform 1900’s

Marriage and Life in Ekaterinburg in the run-up to Revolution

It was in Ekaterinburg that Sir Thomas met his wife Ella Henrietta von Schickendantz, who was from a Bavarian-Swedish family of engineers who had been settled in Siberia for some time. Her father Friedrich had made his fortune there building and running flour mills. The couple married on 3 October 1913 at the Lutheran church of Saints Peter and Paul in Ekaterinburg (sadly destroyed in the Stalinist 1930s) but when war broke out, as enemy aliens, Ella’s family had to leave Ekaterinburg and return to Bavaria. As the wife of the consul she was able to remain for she now had a British passport.

Within three years, and with Britain now at war, Preston was promoted to Consul at Ekaterinburg and with his experience in the mining industry, he was specifically tasked to keep an eye on the highly important production of platinum in the Urals. He reported to the Board of Trade in England on new methods being introduced in platinum mining, where rock bearing platinum was being crushed and washed in similar fashion to extracting gold from quartz in the mines in Chile.

After the Russian Revolution broke in February 1917 and with the Bolshevik coup in October, Preston’s surveillance of that industry on behalf of the British War Office became ever more important when it transpired that the Bolsheviks were shipping out the platinum and gold reserves from Ekaterinburg by rail to Moscow. He was assisted in this by his vice-consul Arthur Thomas, a mining engineer from Cornwall, who had also worked in the Urals.

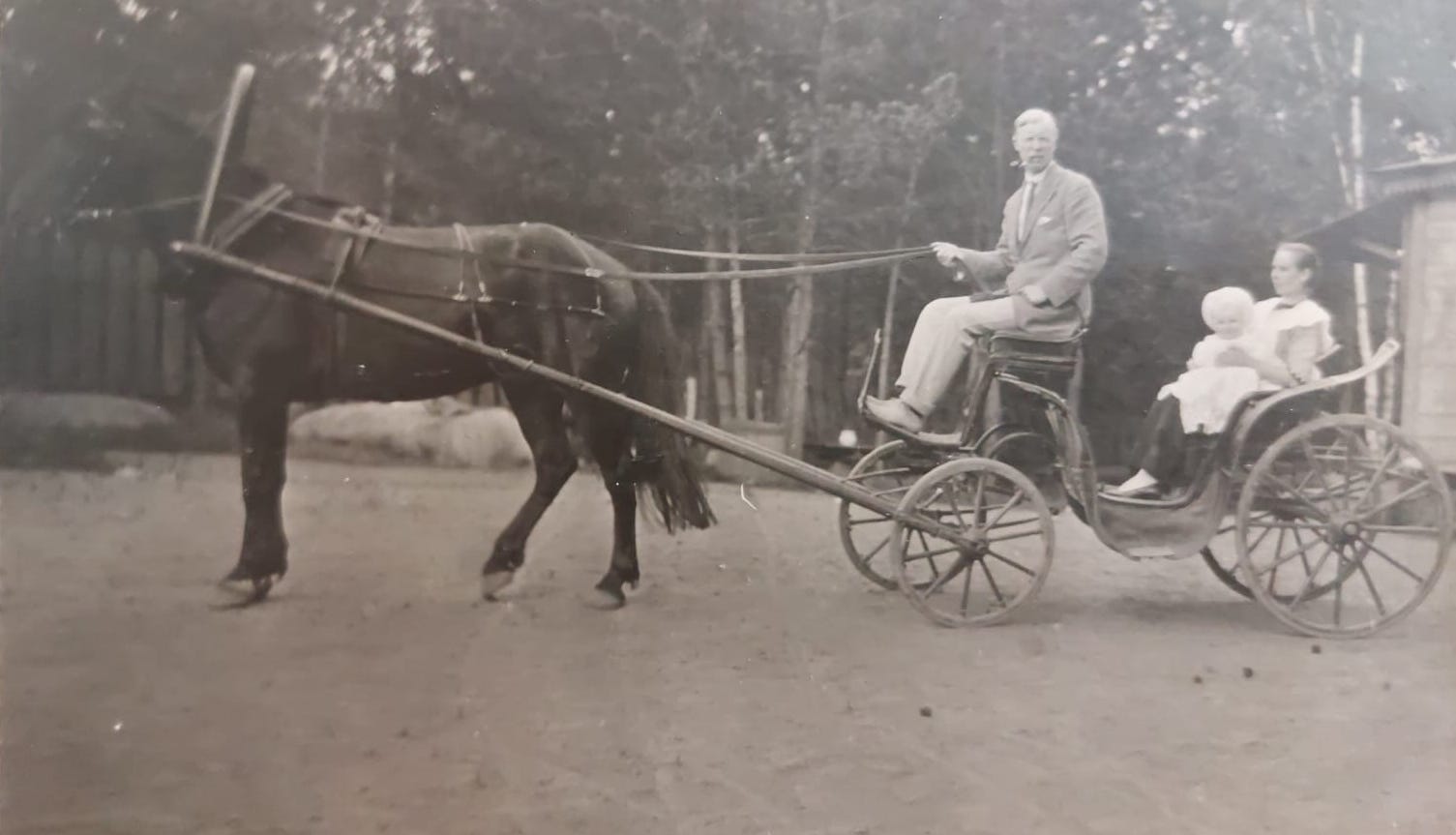

Thomas Preston at Ekaterinburg before the Revolution

Thomas Preston and the Plight of the Romanovs at Ekaterinburg

With the return to England in January 1918 of the British ambassador to Petrograd, Sir George Buchanan, worn down by the stress of his work, no replacement was made for several years. Responsibility for British subjects in Russia for a while devolved to Consul Woodhouse in Petrograd and the secret agent/diplomat Robert Bruce Lockhart in Moscow. Out in Ekaterinburg, and as the Dean of the consular corps there, Thomas Preston had responsibility for all foreign nationals resident in the area ; on behalf of his government, he also constantly pressed the Ural Regional Soviet over the care and treatment of the Romanov family, who from April were incarcerated in the Ipatiev House on Voznesensky Prospekt. The Preston family lived above the British consulate ‘about five doors away’ from the house, according to Sir Thomas, but there is some confusion about its precise location and the building has long since been demolished.

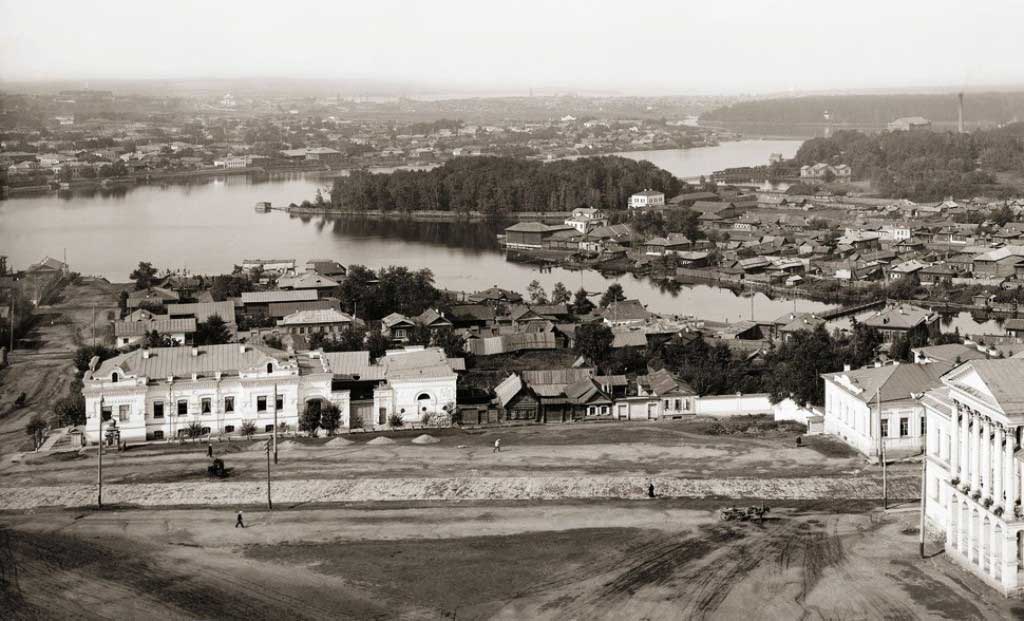

Ipatiev House In Ekaterinburg

It was extremely difficult for Preston to operate effectively during the final days of World War I, made worse by the 1917 Revolution and the ensuing civil war that was raging in Siberia by 1918. During that time the Red Guards in Ekaterinburg had been running riot, terrorising the local population, taking hostages and murdering them and making it difficult even for Preston as British Consul to make any representations to the government without his life being regularly threatened, for the Bolsheviks refused to recognise his status. The desperate situation in Ekaterinburg left him stranded, with only intermittent telegraph contact with London and dwindling funds. Food and other general shortages were becoming serious and he had to fund his consulate throughout 1918 from the proceeds of his mining company. His enforced isolation also meant that he often had to take decisions without consultation with his government.

Fraught Relations with the Leaders of the Ural Regional Soviet

Eventually, Preston managed to establish an ad hoc relationship with some of the members of the Ural Regional Soviet – notably its Deputy Head, Sergey Chutskaev – and had almost daily interviews with him at which he made urgent representations about the treatment of the Romanovs and the refusal of the Soviet to allow them letters in and out, or visitors. Preston also had regular meetings with three members of the Romanov entourage who had been denied permission to join them in the Ipatiev House: the tutors Pierre Gilliard and Sydney Gibbes and the tsaritsa’s companion, Baroness Buxhoeveden, all of whom were stranded in Ekaterinburg and increasingly anxious about the Imperial Family. Day in day out, together with Preston, they ‘wracked their brains to find an answer to the same question: how could we rescue the tsar and his family?’

In later years Preston wearily repeated that despite his best efforts, he had been ‘powerless to intervene’ in preventing the murder of the Romanovs in July 1918. He had in fact concluded prior to that with the greatest regret that ‘any attempt to kidnap the Royal Family and rescue them would have been an act of madness and fraught with the greatest danger to the Royal Family themselves’. He noted also that beyond their few loyal followers in the city ‘there was practically no interest locally in the fate of the Emperor and his family’ and he never got the slightest intimation of any organized plot by the Whites to try and storm the house. Indeed, during the Bolshevik Reign of Terror in the Urals he had been only too well aware of their ‘fanatical hatred of the tsar’.

Departure from Ekaterinburg and British Consul in Leningrad

Ekaterinburg was liberated by the Czech legions at the end of July 1918 and Allied intervention forces arrived soon afterwards. It was, wrote Thomas Preston, ‘like the opening of a door into the sunshine from a huge cave in which we had been kept prisoners for nearly nine months.’ Preston stayed on till the following August, then left for Vladivostok in the Far East, where his second child Tatiana was born (his son Ronald had been born in 1916 in Ekaterinburg), having seen his gold mine confiscated by the Bolsheviks; his wife Ella’s family lost their flour mills too. After a short stay back in England, in August 1922 Preston was sent with a British Trade Mission to the Lenin’s Soviet government in Moscow and subsequently became British Consul at Leningrad, though his wife and children remained in London for the most part.

Saving Jews in Lithuania

After leaving Russia, Preston served in Turin, Italy before being sent to Kaunas in Lithuania in 1929, where in the early days of the war in 1939 he distinguished himself by helping Lithuanian Jews escape. No doubt he recognized the significance of being able here to do something positive, when his hands had been tied in helping the Romanovs in 1918, by issuing around 1,200 British visas, in many cases ignoring the quotas and granting at least 400 illegal ones, to allow Jewish refugees to travel to Palestine and Sweden. In Lithuania his actions, and likewise those of Japanese diplomat Chiune Sugihara, are commemorated every year on Holocaust Memorial Day; he posthumously received the British Hero of the Holocaust award in 2023.

After leaving Lithuania in 1940 due to the threat of a Nazi invasion, Preston served in the embassies at Istanbul and in Cairo, retiring in 1948. In 1963 he inherited the baronetcy at Beeston Hall Norfolk when his cousin, Sir Edward the 5th baronet, died without male heirs.

The Anastasia Saga

An archetypal English gentleman whose years in diplomacy had taught him the art of discretion and who enjoyed his quiet family life in Norfolk, for many years Preston retained a resolute silence about his role in Ekaterinburg at the time of the Romanov murders, (nor did he ever advertise his heroic work in Lithuania). In 1950 he finally gave his own account in his memoirs Before the Curtain (which he had written in Turin in 1928 originally for private circulation as ‘Reminiscences of Ten Years’ Chaos in Russia’) and probably hoped to close the book on that tragic chapter. He apparently destroyed his diary and all personal papers relating to Ekaterinburg after having written it. But a couple of years later controversy over the false Anastasia claimant Anna Anderson gathered momentum when in August 1953 the stage play Anastasia premiered in London, upon which Preston, when asked, tersely insisted ‘I am afraid there is no truth in the story of the survival of the Grand Duchess Anastasia.’ But that didn’t stop Hollywood hyping the story even further with a 1956 film that won Ingrid Bergman an Oscar.

Preston was reluctantly drawn into the case again in January 1960, when asked to provide a sworn affidavit with regard to Anderson’s claim of miraculous survival, when her demand to be recognised was heard in the Hamburg Supreme Court. Having been, as he said, ‘on the spot’ in Ekaterinburg, he could only reiterate, carefully and patiently, that it was his firm belief that the entire family had been murdered in the Ipatiev House on the night of 16/17 July. Anderson’s claim, which had been dragging through the courts for decades, was finally thrown out in 1970 having been heard one final time in the West German Federal Supreme Court.

Preston’s Recall of the Events of July 1918

Preston, resolutely said no more on the subject until he was persuaded in July 1968, on the 50th anniversary of the Romanov murders, to write an article for the Sunday Telegraph. In it he wrote of his intense frustration, of how he had ‘pleaded and blustered for three months with the local Soviet in a vain bid to save the emperor’s life.’ Three years later he was prevailed on by Antony Summers and Tom Mangold to go over it all again for their book The File on the Tsar and be interviewed for a tie-in BBC TV documentary. You can see Sir Thomas’s interview here at 7.29 and 16.16 minutes in:

At that same time he also wrote to the editors of History Today magazine, referring back to what he felt was his definitive 1968 Telegraph article, and reiterating that he had written it ‘so that the civilized world would know that this terrible tragedy actually took place’. He expressed his incredulity that a recent book entitled The Hunt for the Czar claimed that the massacre of the Romanovs was a ‘hoax’ and that the family had been spirited away to Poland, and that the sickly haemophiliac Alexey ‘joined the Polish Army and later transferred to the American Secret Service’. The whole thing, he wrote, was of course ‘a complete cock and bull story’. Preston also sent a letter to The Times emphasising that he, Earl Mountbatten and Grand Duke Vladimir – who were also interviewed for the Summers & Mangold documentary – ‘all stated that we believed that the assassination story was perfectly true’. Privately Mountbatten admitted to Preston that the recent ‘ridiculous books’ claiming the survival of the family ‘would really be laughable if they weren’t so damaging’; and they have indeed remained so, spawning endless false claimants and spurious theories on the subject.

There is no doubt of Sir Thomas Preston’s enduring regret at not being able to do more to help the Romanovs, expressed most eloquently in The Spectator in 1972, which is the last public statement he made on the subject before his death in 1976.

‘Ever since then [1918], I have been haunted by the idea that had I been able to argue with the Ural Soviet for a longer period I might have been able to save

the Russian Royal family.’

Retirement to Beeston Hall, Norfolk

It is a shame that, till recently, little or no mention has ever been made of Sir Thomas’s efforts for Lithuanian Jews (see ‘British Diplomat Who Saved Hundreds of Jews from the Holocaust’, Daily Mail 26 January 2022). Other aspects of his distinguished diplomatic career are also ignored, as too his considerable talent as a pianist and his numerous musical compositions including two ballet scores.

Perhaps we can conclude, therefore, with an affectionate portrait of him that defines the private man whom the public never knew. In a 1978 article about the decline of the British stately home an old friend, Gordon Brook Shepherd, wrote fondly in the Sunday Telegraph of ‘Old Tom’, who had died a year previously, but ‘whose genial spirit still seems to warm the house’. Sir Thomas was, he recalled

‘a magnificently unconventional host, who, at the drop of a napkin, would suddenly abandon the dinner table to thump out Glazunov, Scriabin or his own compositions on the grand piano; and who once threw at me the angry complaint (in Norfolk of all places!) that, as his pheasants belonged to him anyway, why the hell should he have to wait till October 1st every year to shoot and eat them!’

After Sir Thomas’s death, Beeston Hall, where he was buried in the family chapel, passed to his son, Ronald. For many years after leaving Russia, Sir Thomas had tried and failed to secure reparations from the Soviets for the loss of his gold mine in Siberia. Eventually, his widow received a cheque in reparations from President Gorbachev himself – for £50,000.