Sophie Karlovna von Buxhoeveden,

1883-1956

(The Untold Life of Tsaritsa Alexandra’s Lady-in-Waiting)

Part 1

‘So pleasant to have, always friendly, polite no matter what, and a loyal friend.’

Tsaritsa Alexandra in 1913

Sophie Karlovna von Buxhoeveden [styled Буксгевден/Buksgevden in Russian] – or Isa as she was known to the Imperial Family – always thought of herself as a Russian. But although she was born in St Petersburg in 1883, her father Karl Matthias had come from Dorpat [today’s Tartu] in what was then the Governorate of Livonia of which Estonia was part. Karl was descended from a line of eminent Baltic German/Swedish Buxhoevedens who had owned estates at Rupertshof, Dreylingshof, Bolderaa, Lofeldsgof, Gapakshof and Weissenhof in Livonia, but the family’s roots went back to a noble named Bexhövede in the Cuxhaven district of Lower Saxony. The ‘von’ was added when the line was elevated to Counts in 1795 by Friedrich Wilhelm II.

Early Life in Kazan and St Petersburg

Isa’s mother, Lyudmila Petrovna Osokina, was from Kazan in the Middle Volga region, the daughter of a Privy Councillor in the Tsarist bureaucracy. As a child Isa and her brother Peter who had been born in 1886 spent most of their time on the country estate at Cheremychevo; a baby sister Maria born in 1892 had died at the age of two. On the family estate, Isa became very attached to her Scottish governess, Annie Dunsire Mather, who had been her mother’s companion for many years; Annie would remain a loyal fixture in Isa’s life through revolution, the long journey to Tobolsk and exile in Siberia.

With the accession of Nicholas II in 1894, Karl Buxhoeveden, who had studied law at Dorpat, became an official in the 1st Department of the Russian Senate and then when he transferred to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, he moved the family to St Petersburg (though they still spent the summers in Kazan). Soon he was appointed Shtalmeister (Master of the Horse) to the court of Grand Duchess Alexandra Iosifovna, widow of Konstantin Nikolaevich. As children Isa and Peter were friendly with the Konstantinovichi grandchildren.

Isa was first presented to the Dowager Empress during the 1901 court season. As a Dane, Maria Feodorovna favoured Scandinavians and took a liking to Isa and nominated her as one of 200 maids of honour who would attend herself and the Tsaritsa at court. Isa met Alexandra that same summer and again in 1902, but her first official appearance at court came at the close of 1904 when she was invited to join the imperial household for six weeks. This was a time of national crisis with the war against Japan in full swing and Isa immediately found herself recruited, along with many other ladies of the aristocracy, to help at Alexandra’s sklad in the Winter Palace in the organisation of hospital supplies and making garments for the wounded, and soon proved herself invaluable.

Tragedy strikes the Buxhoeveden family

But tragedy struck the Buxhoeveden family at the end of January 1909 when Isa’s 23-year-old brother Peter died in Helsinki. He had joined the Imperial Navy, serving on the cruiser Oleg. But unable to recover from the serious wounds he had received at the Battle of Tsushima during the Russo-Japanese War, he had committed suicide.

Isa’s mother Lyudmila never got over the loss. In October 1910 Karl Buxhoeveden was offered a diplomatic post as Russian Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the Danish king – a significant appointment made with the approval the Danish Dowager Empress. He moved the family to Copenhagen, though Lyudmila, who was lost in grief and suffering ill health, spent half the year in Kazan. In her absence Isa acted as her father’s hostess at the legation.

In 1911, as a further mark of her favour, the Tsaritsa invited Isa to accompany the Imperial Family on a cruise on the Shtandart to Pitkäpaasi, during which she met two other trusted ladies, Ekaterina Schneider (originally hired as a teacher and reader) and Anna Vyrubova. The following year, Alexandra wrote to Isa in Denmark asking her to come and visit the family at their new Livadia palace in Crimea.

A Failed Engagement

It was some time in 1912–13 that Isa, now aged 29, met and became engaged to a young Estonian diplomat, Rolf Ungern-Sternberg. He had just transferred to the Paris embassy after serving in Constantinople as 2nd Secretary. The Buxhoevedens were good friends of Nicolas de Basily former ambassador and a counsellor at the embassy, and Isa probably met Rolf through him. He was from the Baltic nobility and the Tsaritsa was delighted: ‘I am happy for her as she is unhappy at home,’ she wrote to her sister-in-law Eleonore in Darmstadt. ‘Between the parents it’s been bad since the brother’s death.’ Alexandra was, however, sorry at the prospect of losing Isa whom she found ‘so pleasant to have, always friendly, polite no matter what, and a loyal friend.’

However, Isa’s happiness was short lived, for Rolf, turned out to be a career diplomat, driven by a ‘strict sense of duty’ and broke off the engagement to pursue his ambitions in Paris. To console her, Alexandra sent Isa a diamond cypher and invited her to become an official Fraulein (lady-in-waiting) on a salary of 4,000 rubles a year, replacing Lily Obolensky who was leaving after 20 years’ service. Isa thereafter settled down to a life of devotion to the Russian emperor and empress, although there are hints that she remained ever hopeful of finding a husband. At some unspecified point she had briefly been engaged to Prince Vasily Dolgorukov, and Pierre Gilliard thought she had displayed an interest in Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich (though he was ‘not wild about her’).

Isa is inducted into the Romanov court

Before she died in December 1915, the tsaritsa’s closest lady, the terminally ill Sonya Orbeliani, inducted Isa into her duties and the workings of the Romanov court. It soon became clear, however, that Isa’s usefulness would not be confined to mere companionship – of the polite chitchat over tea and embroidery kind – but would be in a more stressful and demanding administrative cum secretarial capacity. With the outbreak of war in 1914 she took on important duties in running Alexandra’s wartime charities and drafting not just her business but also her personal correspondence; Alexandra in her letters to Nicholas at the front frequently talks of ‘doing my papers with Isa’. In addition, she was also asked to help on Grand Duchess Tatiana’s committee for relief work among war victims and her sister Olga’s charitable work with soldiers’ families, in so doing becoming very close to the two eldest Romanov daughters whom she often chaperoned on trips into the capital for meetings etc.

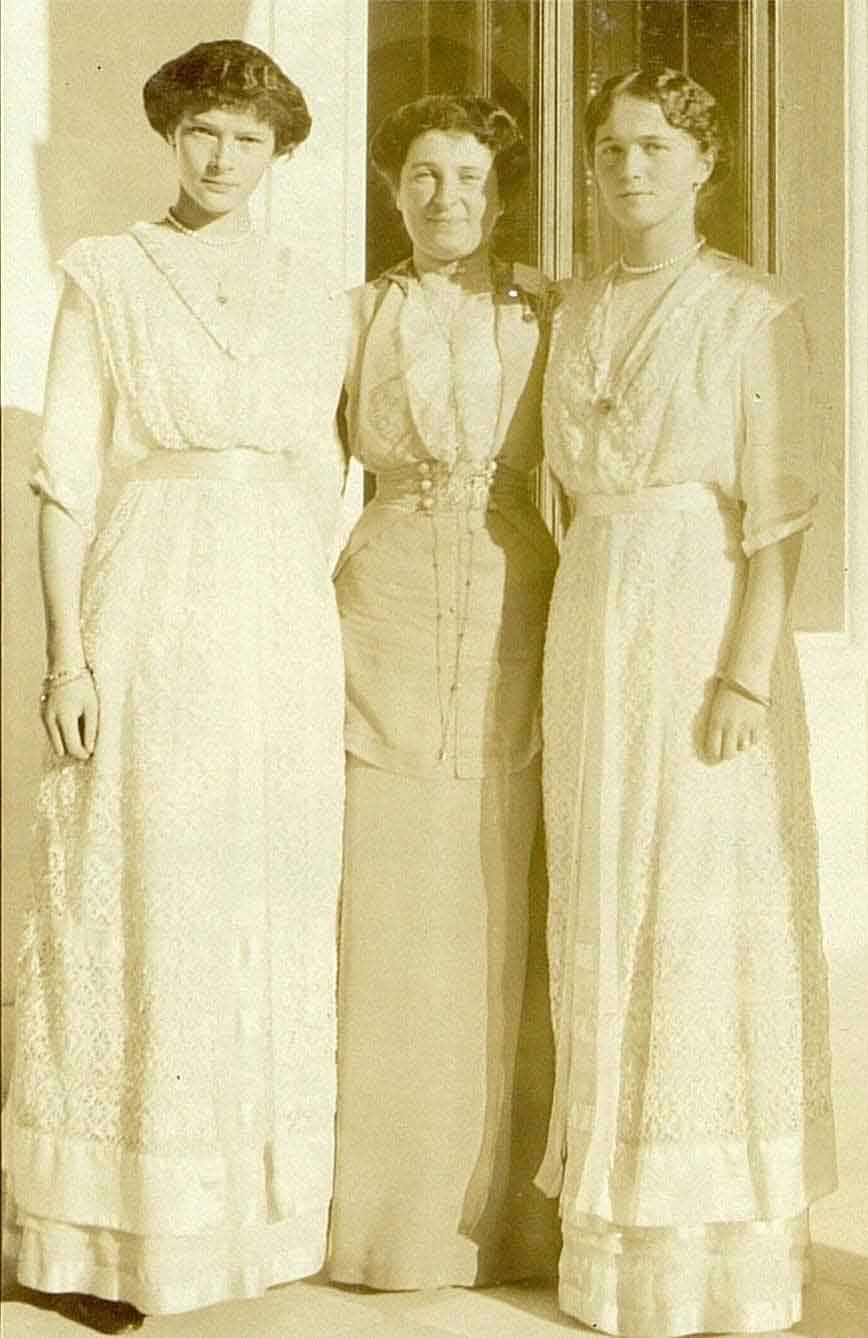

Isa [rhs] with the Romanov children and Anna Vyrubova on board the Shtandart on a trip to the Finnish skerries in 1912

In all her highly personal work for the Imperial Family, Isa made a point of observing the strictest confidentiality and discretion; in her later memoir Before the Storm, she writes of how she avoided the intrigues and backbiting among the two coteries at court – those who favoured Tsaritsa Alexandra’s close companion Anna Vyrubova and those who disliked her. In the period up to the revolution there were in fact only two serving Fräuleins, Isa and Nastenka Hendrikova, who had joined in 1910, for Anna’s role was unofficial.

Revolution in Petrograd

When revolution broke in Petrograd at the end of February 1917 and the tsar abdicated, Isa’s father, on a point of principle, resigned as ambassador in Copenhagen. Her mother died of tuberculosis not long afterwards in Kazan, by which time the Imperial Family were under house arrest at Tsarskoe Selo and Isa was a captive with them. She had not been allowed to leave Tsarskoe to see her mother before she died, but at her request the Imperial Family’s priest, Father Afanasii Belyaev, sang a panikhida for her that was attended by Alexandra and her four daughters.

When the Imperial Family were put on the train to Tobolsk in August 1917, Isa had wanted to go with them but was unable to travel as she was ill with appendicitis and needed an operation. It was not until November that she was able to join the family, having personally lobbied Kerensky to give her a permit to travel, which arrived just as the Provisional Government fell.

One might ask at this point: had she been so anxious about her own safety, as has been alleged, why did Isa so willingly travel all the way to Tobolsk and not try to get out of Russia while she was still close to Finland and the route to neutral Sweden.

Instead, she took 60-year-old Annie Mather, who had come to take care of her after her operation, as companion on an arduous 1,600-mile journey to Siberia, during which they were intimidated by Red Army soldiers packed onto their train. At the end of this frightening experience, when they arrived in Tobolsk on 23 December expecting finally to be reunited with the Imperial Family, Isa and Annie were denied entry to the Governor’s House. They were temporarily put up at the Kornilov house opposite until they found modest lodgings in town. In the meantime, Isa’s father was, according to the daughter of Russian diplomat Arthur Cassini, ‘moving heaven and earth to get her to join him in Oslo’, where he had gone after resigning his diplomatic post.

After Nicholas, Alexandra and Maria were transferred by the Bolsheviks to Ekaterinburg in April 1918, Isa, forced to leave Annie behind in Tobolsk, accompanied Olga, Tatiana, Anastasia and Alexey to join them in May. But once again she was refused permission to be with the family as were most of the entourage who had followed the Romanovs to Ekaterinburg, including the tutors Sydney Gibbes and Pierre Gilliard.

From Tobolsk to Ekaterinburg

For eleven days Isa and her companions languished on the train they had arrived on at Ekaterinburg Station while the Bolsheviks decided what to do with them. During that time, Isa and tutors Sydney Gibbes and Pierre Gilliard made frequent visits to the British Consul Thomas Preston, and as he recalled, ‘spent long hours discussing possible ways and means of saving the royal family’. A later accusation by the false Anastasia that Isa had betrayed the family by telling the Bolsheviks about a supposed rescue plan makes no sense at all, when it is clear she was desperate to see the family saved. Indeed, during my research for The Race to Save the Romanovs, I found no concrete evidence of any rescue plan – had Whites in the area ever been capable of staging one – and certainly not one to which Isa Buxhoeveden, who was stuck on a train at the station, would have been privy. How and why would she have been? But the calumny of her being labelled a traitor has persisted. As too a highly contentious claim that she had greedily held on to money sent to Tobolsk to help the Imperial Family escape, some or all of which a supposed monarchist (but in fact Bolshevik agent) Boris Solovev, claimed to have handed over to her. The ‘evidence’ for this is contradictory, based on the supposed word of one of the most dubious and untrustworthy players in this part of the Romanov story and will be discussed elsewhere.

Stranded in Siberia

Nevertheless, it has been insinuated that Isa kept this money to bribe her way out of Russia. Why else would the Bolsheviks have let her go, her detractors ask, when they took Alexandra’s two other ladies Nastenka Hendrikova and Ekaterina Schneider away to the Ekaterinburg jail and shot them in September 1918? But this begs the question: if Isa was spared, why too were the tutors Sydney Gibbes and Pierre Gilliard? As British consul Thomas Preston noted in his memoir Before the Curtain: ‘It is true that the lives of the Baroness Buxhoeveden and the two foreign tutors were spared; but as I have already stated, their loyalty and devotion in days of great personal danger were no less in consequence; they risked their lives.’

Gibbes was British, Gilliard Swiss and although Isa was a Russian citizen it has been argued that, with the name Buxhoeveden, the Bolsheviks thought she was a Swede. In addition, a report in the Norwegian newspaper Agder in May 1919 stated that when the Tsaritsa was told to provide a list of names of those she had wanted to accompany her to Siberia she had omitted Isa’s name, presumably because Isa was not travelling with them at that time, but remaining in Petrograd to have an operation. It has also been suggested that, before the revolution, she had been given a diplomatic passport to travel freely back and forth to Copenhagen to visit her parents, which may also have helped to save her.

After the Bolsheviks sent Isa back on the train to Tyumen in June 1918 she was again stranded and managed to take lodgings in the town. She earned a little money giving English lessons, as did her devoted companion Annie Mather whom Isa had fetched from Tobolsk as soon as the rail service was restored. But Annie fell sick with enteric fever and died in October and was buried ‘with only a small knot of strangers at the grave.’ It was, wrote Isa, ‘a picture of utter loneliness and desolation.’

Not long afterwards, and now that the Czechs and Whites had liberated Tyumen, Isa finally decided to get out of Siberia, having lingered in fading hope of hearing news of what had happened to the empress and her children, their fate at the time still being uncertain. She wanted to get to England and volunteered as a nurse for the American Red Cross who were taking a Czech hospital train to Omsk. She had left much of her luggage in the safe keeping of Sydney Gibbes who had remained in Ekaterinburg. He arranged the transfer of her things to her in Omsk and also, at some point, lent her 1300 rubles, presumably for her journey out of Russia. (If Isa had stolen the money handed to her at Tobolsk she would hardly have needed a loan to make her journey out of Russia). Other sources say that she and Gibbes had had a shared bank account from which she withdrew money without his permission. Once again there is little or no evidence to go on beyond a tetchy comment by Gibbes in a letter to Pierre Gilliard many years later that Isa was ‘avaricious’ and had not paid the money back. Whether she ever did we shall never know, but we should perhaps bear in mind that Gibbes was a very irritable man with quite a temper, who also abhorred the fact that Isa, like the Tsar, was a heavy smoker. His life, according to author Frances Welch, was ‘peppered with fallings-out’ with erstwhile friends and companions and he was by no means best friends with Gilliard. He clearly blew hot and cold with both him and Isa; in an account of his time with the Imperial Family that Gibbes wrote in 1937 after taking Holy Orders, he specifically commended Isa’s ‘unprecedented honesty’ in her 1928 biography of the empress.

Escape from Omsk on the British Mission Train

After languishing in Omsk during the bitter winter months of January and February 1919, thanks to the crucial assistance of British officers of the Allied Intervention Forces in Siberia, Isa was able to finally make the last leg of her journey out of Russia via the Trans-Siberian railroad to Vladivostok and from there by sea to Japan. In Omsk, a city suffering desperate shortages and overflowing with refugees, she was befriended by Captain Victor Cazalet a member of the Allied Mission, who visited her regularly with a staff officer, Colonel Paul Rodzianko, bringing gifts of cake. It was perishing cold and they would sit together ‘in our great fur coats’ having ‘long talks’ to fight off hypothermia. Finally, on 5 February, they were able to embark on the interminable journey to Vladivostok on General Alfred Knox’s official train that was departing on an inspection up the line.

From Vladivostok, to Japan, to London

After a tense journey, during which the train was threatened by bands of marauding Bolsheviks, Isa finally arrived in Vladivostok on 16 February. As all the hotels were full, General Knox put her up at his own accommodation until Cazalet and the other officers saw her off for Japan. From Yokohama she continued her journey on the Japanese steamer the Tenyo Maru via Honolulu and San Francisco, for England and a brief stop in London, during which she visited King George and Queen Mary for tea. She ‘told us some most interesting things’ according to the king’s diary. Oh, to have been a fly on the wall!