Anna Vyrubova and her American Patrons

‘Nobody, I am very much afraid, is interested in the Czar or his fate. Later it will be different. Many years later, I think.’

American journalist Rheta Childe Dorr

Anna Vyrubova’s devotion to Tsaritsa Alexandra captured in 1909 [Henry Fuller Collection]

Ask any Romanov scholar or enthusiast about the best possible source for photographs of the Imperial Family outside GARF, the Russian State Archive in Moscow, and they will inevitably refer you to the albums held at Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book Library in New Haven, Connecticut. These six leather-bound volumes once belonged to the Tsaritsa Alexandra’s close friend and maid of honour, Anna Vyrubova. After the 1917 Revolution her widowed mother had held the albums in safekeeping until they managed to take them out of Russia when they fled into exile in Finland in 1920. Such has been the international demand for access to the albums in recent years that they have all now been digitized by the Beinecke and made available for public view. A brief visual overview of them can be seen here:

Anna Vyrubova’s Romanov Photograph Albums

Covering the years 1907 to 1915 the Anna Vyrubova albums are a treasured resource, containing as they do around 3,000 photographs of the Imperial family carefully collected by Vyrubova during her time at the Russian court from 1905 and arranged and mounted with the help of both Nicholas and Alexandra. After the 1917 Revolution when the Romanovs were sent to Siberian exile and their eventual deaths, Vyrubova was arrested and spent five months in an underground cell at the notorious Peter and Paul Fortress in St Petersburg under interrogation for supposed treasonous association with Rasputin and the former Empress. She narrowly escaped being shot; after her release she fled St Petersburg with her mother – bringing her precious photo albums with her – by sledge across the ice of the Gulf of Finland, and took refuge at her parents’ dacha 20 miles from the border at Terijoki.

There is no doubt that Vyrubova suffered terribly for her loyalty to the Romanovs, and never recovered either her mental or physical equilibrium after her experiences. But in the annals of late Imperial Russian history she has always been a much reviled personality, a ‘controversial and polarising figure’, according to historian Doug Smith. She had many enemies at court, and her detractors were cruel and vocal in their criticism, describing her variously as stupid, obstinate, childishly silly and something of a hysteric; worse, even her supporters agreed that she was dangerously naïve and lacking in any real political understanding.

It was the notable American historian, Robert K Massie, long-celebrated for his ground-breaking 1967 book Nicholas and Alexandra, who first drew attention to the presence of the Vyrubova albums at the Beinecke Library, when he came across them during his research in 1966. He immediately grasped their huge importance to Romanov scholarship; the international success of his book ensured that soon everyone would know about them. But how had the albums reached the USA?

Anna with one of her treasured Romanov photograph albums [Wikipedia]

The Robert D Brewster Bequest

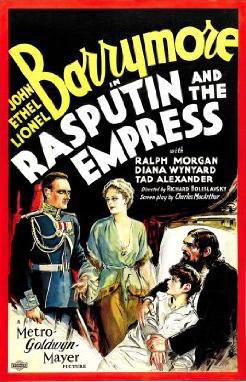

In 1937, they were purchased from Anna Vyrubova, now living in penury in Finland, by an American philanthropist and collector, Robert D. Brewster. As a young man he developed an interest in the Romanovs and taught himself Russian. His interest was further piqued seeing the sensational 1932 Hollywood film Rasputin and the Empress. At the time it was said that one of the characters in the film, Natasha, was based on Anna Vyrubova. Brewster managed to track down her brother Sergey Taneev – by then an exile in New York – who put him in touch with Anna in Finland.

The apartment block in Viborg where Anna lived in the 1930s, [Wiipuri Association CC BY 4.0]

In August 1937 Brewster travelled out to Viborg in Finland to see her and was shocked to find her ‘quite a wreck, poor thing’. Aware of Anna’s difficult financial circumstances, he persuaded her to sell him all but one of her seven precious Romanov photo albums (the seventh she presented to Queen Louise of Sweden). In the years that followed he also bought a few loose Romanov photographs and some of Anna’s precious letters from the family that she had long resisted parting with.

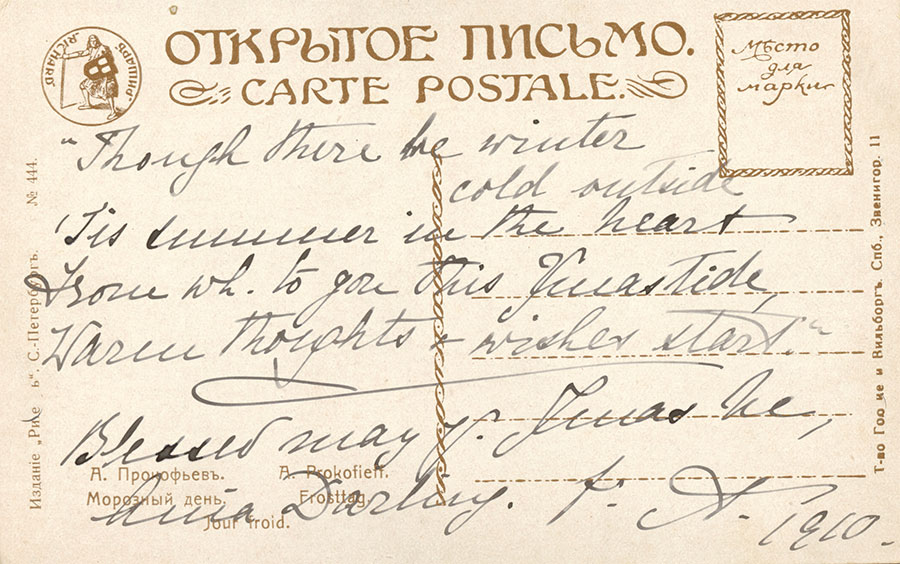

One of Anna Vyrubova’s postcards from Tsaritsa Alexandra, 1910 [Henry Fuller Collection]

In 1951 Brewster donated the albums and the letters to his alma mater, Yale. But until Robert K. Massie discovered their presence in the Beinecke library, no one had registered their importance, hidden away as they were as ‘Romanov memorabilia’ at a time before publication of his book – and the subsequent 1971 film of it – opened the floodgates of worldwide interest in the Romanovs.

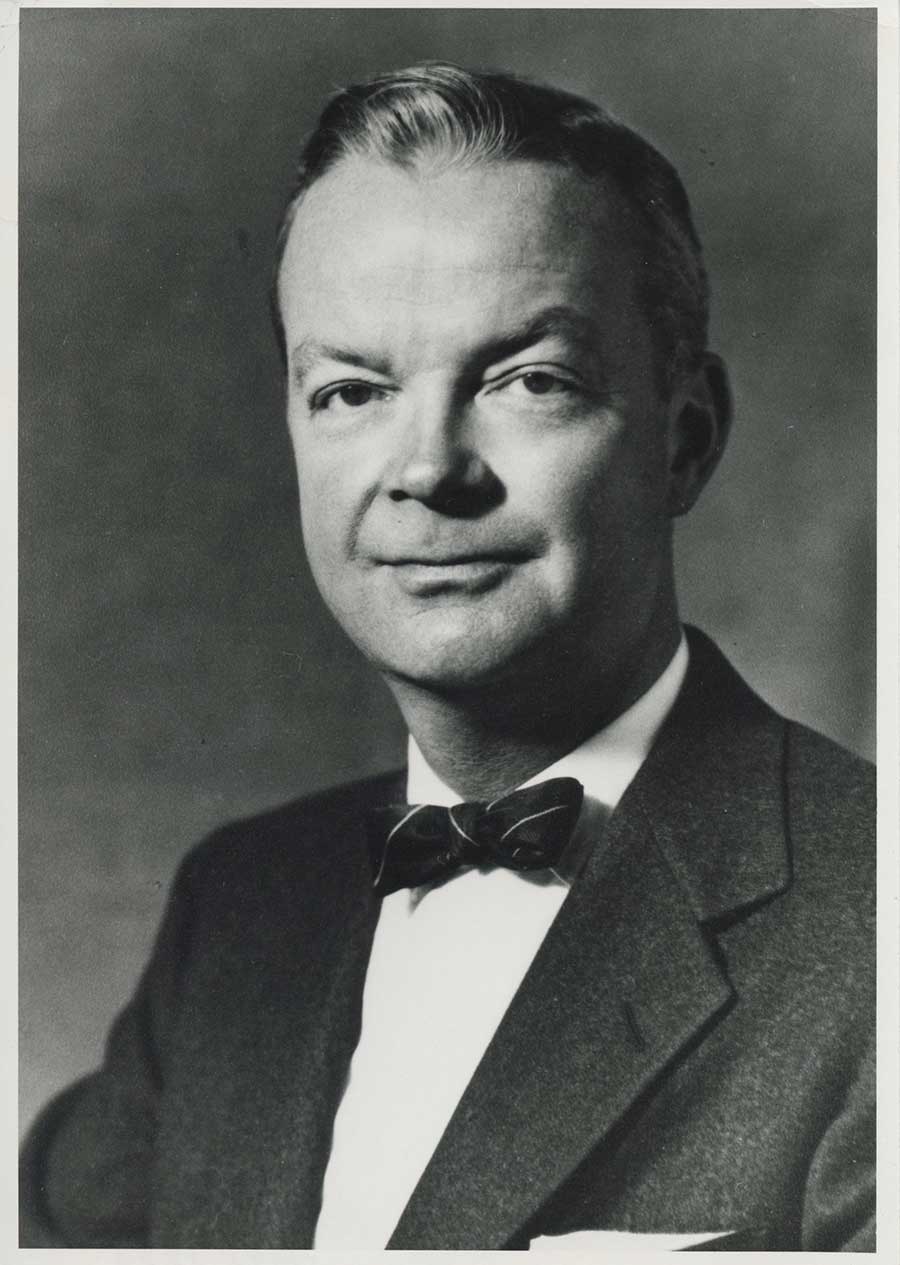

Robert Dows Brewster (1916-1995) is a very hard man to pin down, with virtually no web presence, so much so that I am yet to locate a photograph of him. As well as being a passionate Russophile, who travelled extensively in the Soviet Union, he was a painter and art collector whose family wealth was built on Standard Oil. He appears never to have married or had children and so Art, History and Romanov studies benefitted ultimately from his great generosity.

The Henry Melville Fuller Bequest

But that is not the end of the story. Thirty miles north of Yale, located in the Watkinson Library of Trinity College Hartford another important facet of the Anna Vyrubova legacy has, till now, also been largely overlooked.

Most people assume it was Brewster who made the original Anna Vyrubova connection and helped preserve her important legacy. But in fact Brewster was preceded in this regard by another equally elusive, extremely private American philanthropist and collector – Henry Melville Fuller – who first contacted her in Finland in 1931 when he was only 17 years old and later corresponded with Brewster about her plight and how best to preserve her archive

Henry Melville Fuller 1914–2001 [Henry Fuller Collection]

In 2001 Henry Melville Fuller, (1914-2001) left a bequest of $39 million to Trinity College, having graduated there in 1938. His considerable fortune appears to have been made from stockbroking and clever investment on Wall Street and throughout his quiet, seemingly inconsequential life, he lived unostentatiously. Much like Robert Brewster, he never married or had children. It was while studying at Harvard in the 1920s, that Fuller too developed an abiding passion for all things Russian and a particular interest in the Romanov family.

Meetings with Anna Vyburova in Finland

In 1931, after connecting with Anna Vyrubova via a New York manuscript dealer, he made a pilgrimage to Helsinki to visit her. He returned again in 1933 to spend five days with her, at Anna’s specific request, at the Valamo monastery on Lake Ladoga. In November 1923, Anna had taken secret vows there as a Russian Orthodox lay nun. She was not resident there, due to her longstanding injuries from a railway accident in 1915 which had left her hobbling with a crutch, but Valamo was always where she felt happiest and most at peace.

Anna recovering from her railway accident in 1916 [Wikipedia]

Returning to Harvard, 19-year old Fuller wrote up his experiences of that meeting for an undergraduate English paper – ‘Anna Viroubova Speaks’ – that he presented at Trinity in 1935 (Henry Fuller Collection, Box 2: Series III, folder1). He was drawn to Anna because, Fuller said, he had ‘heard and read such weirdly impossible yarns’ about her:

‘People, whose word should have been above reproach, told me that she was infinitely more criminal that Lucrezia Borgia.’

Because of this, during all her years in exile till then Anna was bitterly hated by many Russians and went into retreat, consistently refusing to be interviewed; indeed friends advised her against ‘emerging from the safety and seclusion’ of her life with her mother in Finland.

The ‘Rasputin and the Empress’ Scandal

What Fuller found when they met at Valamo – and it was a view reinforced over the many years of their correspondence that followed – was a sad, lonely woman, ‘a total invalid, forgotten personally by everyone, yet a name still denounced and vilified in practically every book or article dealing with the end of the Russian monarchy.’ From their conversations, Fuller concluded that Anna had been the hapless victim of her own naivety, who now found her only consolation in religion. Her fear of personal attack and reluctance to defend herself was also reflected in her failure to sue the makers of Rasputin and the Empress for basing the role of Natasha on her. Soon she was pre-empted, when Prince Felix Yusupov launched a famous libel case against MGM for supposedly modelling Natsha’s character on his wife Irina. According to Fuller, Anna ‘had been too timid to claim that it was she who was misrepresented not Irina’.

When she was with Fuller, Anna spoke quite candidly of Tsar Nicholas, insisting that his opposition to the State Duma, which he repeatedly shut down, came not from a desire to hold on to personal power but that ‘he hesitated to create a house of popular representation because he knew how ill-prepared were the Russian people for government.’ Anna found Nicholas ‘so reserved he seemed to fear any self-revealment’; ‘it was impossible to arouse him to the importance of things,’ she said. It was the Tsaritsa Alexandra to whom she remained eternally devoted; she struck Anna as a woman to whom ‘suffering always made a strong appeal’. ‘Few people, even in Russia, ever knew how much the Empress did for the poor, the sick and the helpless,’ she insisted. But it was her son, the Tsarevich Alexey, who was the focus of Alexandra’s entire world:

‘In the person of that frail, winsome child, you have the explanation of the Empress; you have the key for the abdication of Nicholas; and most of all, you have the reason for Rasputin.’

Henry Fuller’s five days with Anna Vyrubova in 1933 marked the beginning of a friendship that lasted until her death in 1964. The Fuller Collection at Trinity holds 169 letters and postcards she sent to Fuller over those years, as well as some signed Romanov postcards and loose photographs – a mixture of prints and an album of originals relating to the years 1910–12. Fuller also acquired a few of Anna’s letters from the Tsaritsa, notably an important letter written from Tobolsk in March 1918 that she only allowed him to have on condition that he never sold it. Her own letters – an outpouring of disorganized thoughts in a scribbly but readable hand, are a rather painful read. In them, Anna repeatedly catalogues her endless financial difficulties, her worries about her elderly mother with whom she lived, and even her brother over in New York who was in poor health. But their overriding preoccupation is her at times desperate attempts to sell items from her Romanov collection – piecemeal – as and when her money ran out and she couldn’t pay her rent.

Anna Vyrubova in 1957, she died in Helsinki in 1964 [Wikipedia]

It was in fact Fuller who first tried to find a buyer for her Romanov photograph albums. A year after their meeting in 1933, he wrote to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard, and various collectors of Russian art including Armand Hammer and Alexander Schaffer, in a concerted attempt to effect the sale not just of the albums, but of Vyrubova’s postcards and Christmas cards from Tsaritsa Alexandra and her children. She was however conscience stricken about having to sell any letters she had received from the Empress: ‘I should like only such people who venerate her memory to own them,’ she told Fuller, but recurring financial necessity meant she prevaricated endlessly over selling them.

Sadly for Anna, in the early 1930s, at a time of economic depression, nobody was interested in Romanov memorabilia. Everyone turned her down; for the most part all that Fuller was able to sell were a few postcards for a few dollars here and there and a couple of Wedgewood medallions of Nicholas and Alexandra given to her at Christmas 1915. For months Fuller tried to sell her St Catherine’s order to Mr Hammer or Mr Schaffer for $200; its fate is unknown. Interestingly, the Fuller Collection contains a few letters to Fuller from Brewster in 1938, indicating that he too was trying to find buyers for Anna’s Romanov items, and, three years earlier, another American had been recruited by Fuller to help. This was feminist and journalist Rheta Childe Dorr, which brings us to the most revealing letters in the Henry Fuller Collection.

Rheta Childe Dorr and Anna Vyrubova’s Memoirs of the Russian Court

With money worries forever hounding her, Anna at times even considered going to the US on a lecture tour – but her poor health prevented it. She thought about trying to write another book but told Henry Fuller she needed a collaborator. In this regard, one important fact becomes clear from the Fuller Collection and that is the extent to which Anna’s Memoirs of the Russian Court, published in 1923 were pulled into shape for her by Rheta Childe Dorr.

American journalist Rheta Childe Dorr (1866-1948) [Wikipedia]

When Dorr was in Petrograd reporting on the Russian Revolution in 1917, she had been curious to meet Anna Vyrubova, having been told that she was ‘the worst woman in Russia’. She described their meeting in her book Inside the Russian Revolution (1917) and updated her account of Vyrubova in A Woman of Fifty (1925), where she outlined the extent of her contribution in helping Vyrubova sort out her voluminous handwritten notes and correcting and revising her manuscript. This gets a passing mention in chapter XXI of the published Memoirs where Vyrubova made a discreet acknowledgement of Dorr’s ‘encouragement’ in her attempt at authorship, somewhat minimizing her crucial contribution. It was in fact the second time Dorr performed such a role, for in 1914 she ghosted the memoirs of the suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst. Privately, Dorr wrote to Henry Fuller that any attempt to work with Vyrubova on a book would be a tough call. ‘When you speak of Anna writing, or even being interviewed for publication, you cannot know what a job I had getting that book out of her,’ she told him.

In her letters to Fuller, Dorr recalled how she spent two months with Vyrubova in Badenweiler in 1922 helping her draft her memoir: ‘I had to cross examine her like a trial lawyer to get the right stuff out of her.’ As a highly efficient, no-nonsense journalist with an eye for a good story, Dorr knew that Anna’s book ‘would be valuable as a reference work for centuries to come’ and she restricted her narrative to things that Anna knew of personally. As far as Dorr was concerned, it was ‘a plain matter of fact that people who spend their lives in palaces, as personal attendants of monarchs are about the most ignorant I know of when it comes to outside matters. They cannot see the economic, social or political drift of their own countries, let alone foreign countries.’ For all the condemnation of her for being a devoted acolyte, Anna, she concluded, really knew very little about Rasputin. In her memoir ‘her object was to make the family as innocent as possible and as free from Rasputin’s influence in politics.’

Preserving Anna’s Legacy

Throughout her letters to Fuller, Dorr was even handed in her assessment of Anna’s gullibility and had no doubt how much she had suffered for her closeness to Rasputin and Alexandra: ‘I cannot believe that she was ever anything evil or even unvirtuous in the Puritan sense of the word. She was, I firmly believe, merely a tool of the Tsarina, doing her bidding without question. She certainly was the go-between of Rasputin and the Tsarina, and that may be the reason why she came in for so much calumny and abuse.’

In the end, Dorr and Fuller agreed that Vyrubova had ‘amply atoned for anything she ever did in her whole lifetime.’ Dorr had long despaired at Anna’s lack of any business sense, hence her difficulties now with capitalizing on her archive but she wrote to the Morgan library, encouraging them to buy the photograph albums. She too was struggling financially during the Depression years – it was ‘terrible for writers, nothing much except fiction being saleable’. In May 1935 Dorr told Fuller she had been trying to place an article she had written on ‘The Romanoff Case: An Almost Perfect Crime’, to no avail. She held out no hope for Anna selling her photograph collection, remarking with considerable prescience:

‘If Anna is up in the air about the pictures she will just have to stay there. There will be no sale for the pictures at present, just as I fear there will be no sale for my article, although it contains matter never before published except in France. Nobody, I am very much afraid, is interested in the Czar or his fate. Later it will be different. Many years later, I think.’

How much Brewster paid for the Romanov photograph albums when he acquired them from Anna Vyrubova in 1937 has not been made public and the Beinecke have no details of the bequest. Undoubtedly it was a fraction of what they would fetch today at auction; likewise the many greetings cards, postcards and letters that Fuller sold on Anna’s behalf for a mere handful of dollars. But he and Robert Brewster are owed a debt of gratitude for securing the survival of Anna’s legacy. It is a shame that the role Rheta Childe Dorr played in shaping her memoirs has barely been acknowledged beyond a sentence in Wikipedia; the rare survival of Dorr’s candid letters to Henry Fuller are all we have of her, an important and still underrated pioneer woman journalist who witnessed the Russian revolution in 1917. Unlike Anna Vyrubova, she has no surviving archive.

Anna Vyrubova’s grave at Helsinki Orthodox Cemetery, Finland [julia&keld, FindaGrave]

I am grateful to the Watkinson Library at Trinity College for allowing me special remote access to the Henry Fuller Collection and to Archives Librarian, Casey Machenheimer, who went out of her way to assist me in providing digital scans. Details of the collection can be found here: